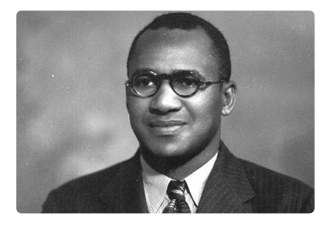

John L. LeFlore was born in Mobile, Alabama on May 17, 1903. Like most African Americans growing up in the Deep South at the beginning of the 20th century, LeFlore experienced many indignities. But LeFlore refused to accept the status quo and for more than 50 years he was the voice and face of the civil rights movement along the Gulf Coast. LeFlore played a key role in the desegregation of the Mobile public schools and changing the at-large election format in Mobile to ensure African Americans had a voice in government.

After a confrontation with the police in 1925, LeFlore’s leadership turned the beleaguered and inactive Mobile branch of the NAACP into one of the most productive branches in the state. He was named executive secretary and held that position until 1956, when the state of Alabama secured an injunction against the NAACP prohibiting the organization from operating in the state. However, the ban did not stop LeFlore from continuing his fight for equal rights. In 1936 he helped establish the NAACP’s Regional Conference of Southern Branches and became its first chairman. In the 1940s and 50s, LeFlore, serving as a news correspondent for the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, and the Associated Negro Press, reported on numerous civil rights violations occurring in the South.

LeFlore recognized that the only chance African Americans had to achieve true equality and justice in Alabama would be through active participation in the political process. Beginning in 1957 the Non-Partisan Voters’ League, an organization LeFlore and other activists reorganized after the banning of the NAACP in Alabama, began publishing the “Pink Sheets.” The Pink Sheets listed state and local candidates who were considered advocates of the civil rights movement. Candidates listed on the Pink Sheets carried the majority of the African American votes during the 12 years they were published. Although pink in color, the Pink Sheets caused candidates to finally see the colors “black and brown” in a different light.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, LeFlore and the Non-Partisan Voters’ League brought hundreds of incidents of discrimination to light and lobbied for equality. In 1963 working with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, LeFlore filed a suit to desegregate Mobile’s public schools. Thirty-four years laterBirdie Mae Davis v. Mobile County Board of Education was finally dismissed, making it the longest-running secondary school desegregation case in American history.

In the early 1960s LeFlore successfully desegregated several downtown businesses, restaurants, and the city-owned golf course. Mobile’s desegregation process appeared to be on a smoother path than other Alabama cities. LeFlore was praised for leading a peaceful transition throughout such a turbulent time. However, LeFlore did not escape the terror tactics that many civil rights leaders experienced. In 1967 LeFlore’s home was fired bombed.

In 1966 LeFlore was the first African American appointed to the Mobile Housing Board. In 1973 LeFlore made an unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Senate, but the following year LeFlore and Gary Cooper, became the first African Americans elected to the state legislature from Mobile since Reconstruction.

In addition to LeFlore’s civil rights activities, he also supported and served on numerous organizations and committees. Some of the issues he worked on included prison reform, health and family planning, veterans’ rights, labor unions, and public education. On January 31, 1976, LeFlore died of a heart attack.