By Dr. Martha V. Bouyer

Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson is noted as the first woman of any race, to be licensed/certified to be a medical doctor in Alabama in 1891. The fact that she was a Black woman made her accomplishment so great that even the New York Times took notice.

Above: The Tanner Family

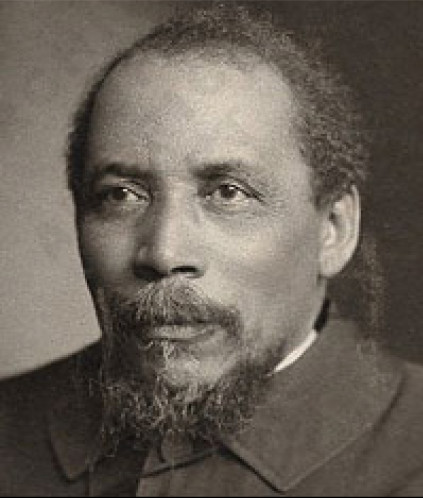

Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson was the eldest of nine children born to Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner and Mrs. Sara Elizabeth Miller Tanner. Dr. Dillon Johnson was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on October 17,1864. The family later moved to Philadelphia where her father served as Bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. He also published the Christian Review, a publication for members of the church.

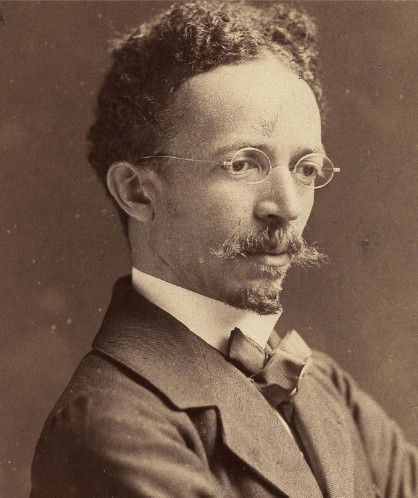

Dr. Johnson came from a very distinguished family. Her brother was the world-renowned painter, Henry Ossawa Tanner. Her niece was Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, the first Black woman in the United States to receive a Ph.D. and the first president of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority.

Benjamin Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander

At the age of 22, Dr. Johnson married Charles Dillon in 1886. The couple moved to Trenton, New Jersey. To this union, a daughter, Sadie was born. In 1888, Charles died from complications of pneumonia and Halle moved back to Philadelphia to live with her parents and siblings. After moving back home, she decided to return to school and pursue a degree in general medicine at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Dr. Johnson was the only Black in her class and graduated in 1891, with honors.

1891 Graduating Class of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. Dr. Johnson top row, circled on the right.

At the time of her graduation, Dr. Booker T. Washington was looking for someone to serve as a medical doctor for Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The doctor would not only serve the 450 students enrolled at the school, but the faculty and the community. He had written a letter to the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in hopes of getting someone to fill the position. This was a wonderful opportunity for any aspiring young doctor, but for Dr. Dillon Johnson it was an answer to a call of service on her life. The position offered a very modest salary, room and board, and an opportunity to change lives for Black people in living in Macon County, Alabama. Dr. Dillon answered the call and moved to Tuskegee.

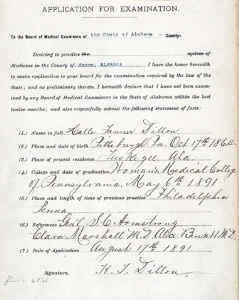

From the moment she said yes, the challenge was on. Although she had a degree in general medicine, she still had to pass the Alabama Medical exam, which was said to be one of the most stringent in the nation. She started out with what appeared to be two strikes against her, she was a woman and Black. Up until this time, no woman had passed the Alabama exam. She began this process by submitting her application to the board of examiners on August 17, 1891, and started the exam soon after.

Dr. Dillon was not on her own. Dr. Washington had convinced Dr. Cornelius N. Dorsette, a friend from Hampton Institute, to come to Montgomery several years earlier and set up a medical practice. Dr. Dorsette is thought to be the first licensed/certified Black doctor in Alabama. He served as a Trustee of Tuskegee and as Dr. Washington’s personal physician. He served as her mentor and tutor and along with other Black doctors, helped her prepare for the exam.

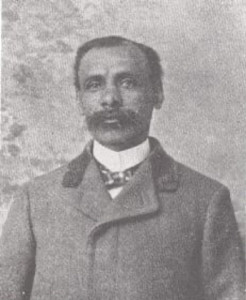

Dr. Cornelius N. Dorsette

Dr. Tanner Dillon’s application to the Alabama board of medical examiners, 1891.

Dr. Peter Bryce, one of her examiners, was superintendent of the Alabama Insane Asylum. Today, the hospital bears his name for the contributions Dr. Bryce made to treating people with mental issues. Dr. Bryce tested Dr. Dillon on medical jurisprudence. Jerome Cochran, state health officer and the primary force behind the Medical Licensure Act of 1877, examined Dr. Dillon in chemistry. Her examiner in natural history and diagnosis of diseases was George A. Ketchum, Dean of the Medical College of Alabama from 1885 until his death in 1906. Dr. Ketchum was also involved in creating the Medical Association of the State of Alabama (MASA) in 1847. James T. Searcy, her examiner in hygiene, became superintendent of the Alabama Insane Hospital following Bryce’s death. Dillon was examined in obstetrical operations by John B. Gaston, who had served as president of MASA in 1882.

Dr. Dillon passed the examinations. Early in the process, Walter Bressell, clerk of the Alabama State Board of Health, told her that she had done well in chemistry. That information bolstered her confidence. She told Dr. Washington in a letter during the exams that she felt she could pass if graded fairly and acknowledged that the surgery portion was very difficult. She so impressed the members of the board that her performance on the examination was noted in the 1892 MASA journal Transactions.

Nursing Students at Tuskegee Institute, c. 1890s.

The examination took several formats that included oral questions followed by written responses from Dr. Dillon. In order to pass, Dr. Dillon needed a score of 75%. She passed the exam with a score of 78.81%, 3.81% higher than the required score.

When Dr. Dillon first came to work at Tuskegee, her father, Bishop Benjamin Tanner came with her and stayed with her for a year in Alabama serving as a church lecturer. Dr. Dillon served as the doctor for the Institute’s students, staff members and their families, and the community. She would also establish a pharmacy where she compounded medicine for her patients, taught two classes each semester on anatomy and hygiene, and established a nursing school.

Dr. Dillon served in these roles from 1891 to 1894. She married a fellow member of the faculty, Reverend John Quincy Johnson in 1894. The Johnson’s would leave Tuskegee for Columbia, South Carolina where Rev. Johnson became president of Allen University. As Rev. Johnson pursed his education, the family moved to several cities including Hartford, Connecticut; Atlanta, Georgia; and Princeton; New Jersey. The couple had three sons: John Quincy Jr., who was named after his father; Benjamin T. named after her father; and Henry Tanner named after her brother, the artist, Henry Ossawa Tanner.

In 1900, the family settled in Nashville, Tennessee, where Rev. Johnson served as pastor of the Saint James AME Church. On April 26,1901, Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson died of dysentery during childbirth.

A charge to keep I have, A God to glorify,

A never-dying soul to save,

And fit it for the sky.

To serve the present age, My calling to fulfill:

Oh, may it all my pow’rs engage

To do my Master’s will!

(Charles Wesley)

RESOURCES

- Blassingame, John W., and Pete Daniel. The Booker T. Washington Papers. Volumes 1-14. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Hine, Darlene. Black Women in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Washington, Booker T. “Training Colored Nurses at Tuskegee.” American Journal of Nursing 11 (October 1910): 167-71