The Alabama African American Mural Trail is a part of public artwork by commissioned and non-commissioned artists and public organizations.

The artwork is free and continues to grow throughout Alabama’s cities, towns, and countryside. Their purpose of the artwork is to raise awareness about historical and current issues; preserve the transforming history of the state as a whole; advocate for peace and justice; and help communities value public art.

Alabama is a complex and diverse state. It has a long history saturated with both good and bad, and both stereotypes and realities that sometimes affects the reputation proceeding it. From the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement to rocket science to southern hospitality and the beauty of nature, the mural trail illustrates some of the richest cultural experiences of a people. The murals in this article unite historical accounts and events that have occurred within the state and may have affected the nation and the world in some way.

Let’s begin an illustrative trail tour of some of the most phenomenal murals throughout the state that represent our history. Let’s start at the base of the state. Beginning at the Gulf port city of Mobile where Alabama’s history began, let’s follow our African American Mural Trail through the Wiregrass, the Black Belt, Central and North Alabama.

The above mural is called The Clotilde. It is one of a series of murals depicting Mobile’s history by John Augustus Walker, 1936. (Source: Alabama Department of Archives and History). The mural currently hangs in the main post office of the city of Mobile.

The Gulf Port City of Mobile

In the mid-1930s, during the Great Depression, the U.S. federal government initiated a series of programs that were meant to provide economic relief to unemployed visual artists. As part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and its Works Progress Administration (WPA) effort, the federal government hired more than 10,000 artists to create works of art across the country, in a wide variety of forms — murals, theater, fine arts, music, writing, design, and more. It was part of a plan to stimulate economic recovery for a country reeling from the Great Depression, widespread poverty, and high unemployment.

But it was also much more than that. Sandwiched between the World Wars, the arts projects overseen by the WPA — which included the Federal Art Project focused on the fine arts as well as initiatives in other disciplines — were meant to help the United States develop its own distinct style of artmaking.

This van Gogh-inspired mural entitled The Souls of Mobile is located on the side of Hailey’s Bar and was designed by street artist Ginger Woechan.

She got inspiration from the phrase “love and light” and worked to highlight Mobile’s vibrant culture. This mural serves as an ode to downtown Mobile.

Dothan, Alabama

When you think of the peanut industry, what state do you think of? Though it has its roots in Georgia, peanuts are also an Alabama staple. That’s why this eye-catching mural by Bruce Ricketts and Susan Tooke commemorates the peanut industry. Thousands of people from all over south Alabama, Georgia, and the Florida panhandle visit Dothan during their largest and most anticipated event of the year, the National Peanut Festival.

On a near freezing cold day, Dr. George Washington Carver was the guest speaker at the first Festival. Dr. Carver introduced peanuts to the Wiregrass, and they saved the area after boll weevils destroyed the cotton crops. Since 1938, each November the entire city comes alive with vendors, exhibitions, and all the excitement the festival brings.

A Tribute to Sherman Rose

Dothan native Sherman Rose soared to great heights in the military in World War II. The above mural by Wes Hardin shows Rose during different stages of his life, including when he made history as the very first African American flight instructor at famous Fort Rucker. This mural is a tribute to Rose, a resident of Dothan and one of the original Tuskegee Airmen. The full title of this mural is A Tribute to Sherman Rose.

Sherman Rose was a flight instructor who helped train the first Black military aviators in the history of the United States, the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. It was painted by Wes Hardin in 2001. It is just one of the Dothan murals that commemorate an African American.

Phenix City, Alabama

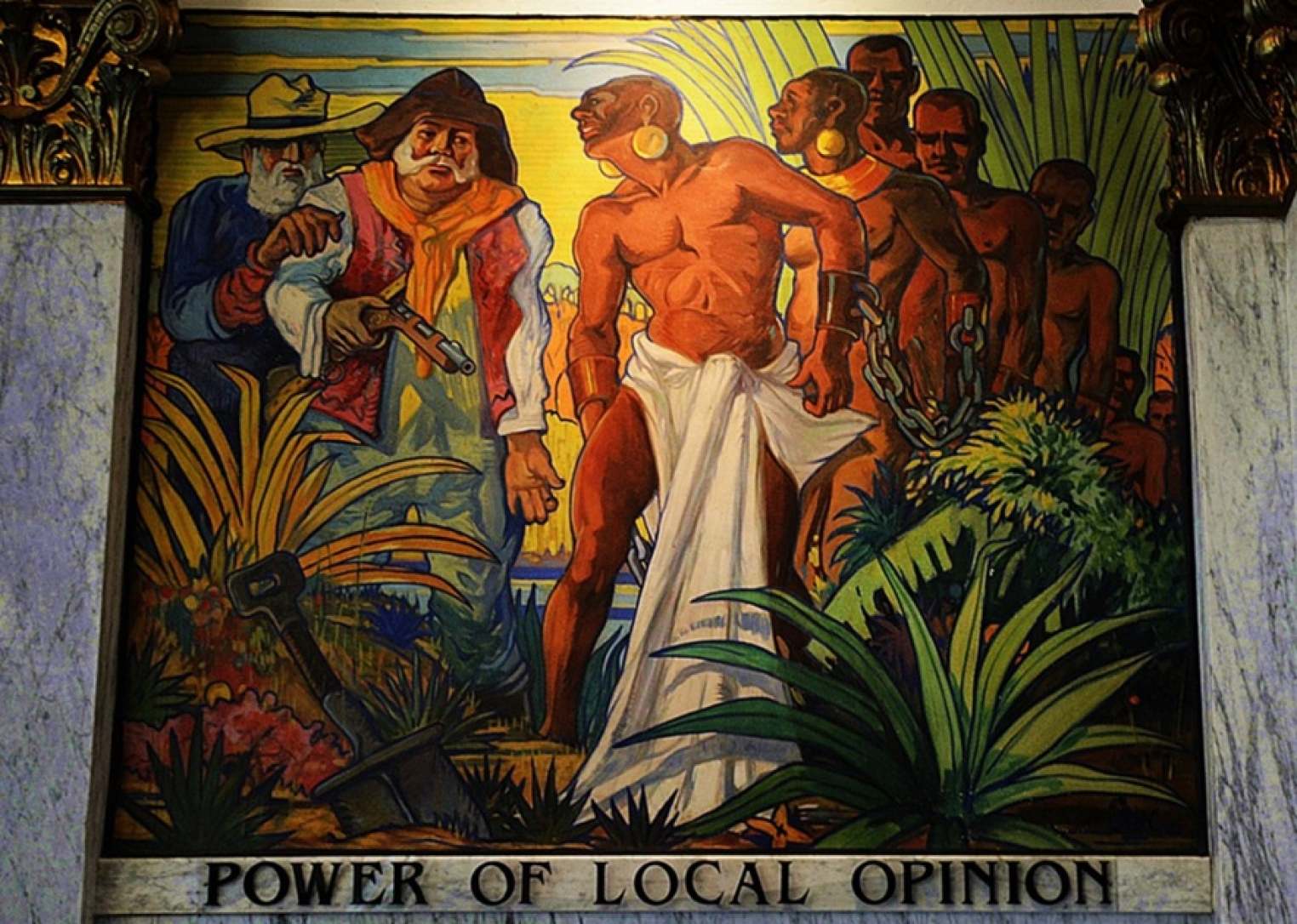

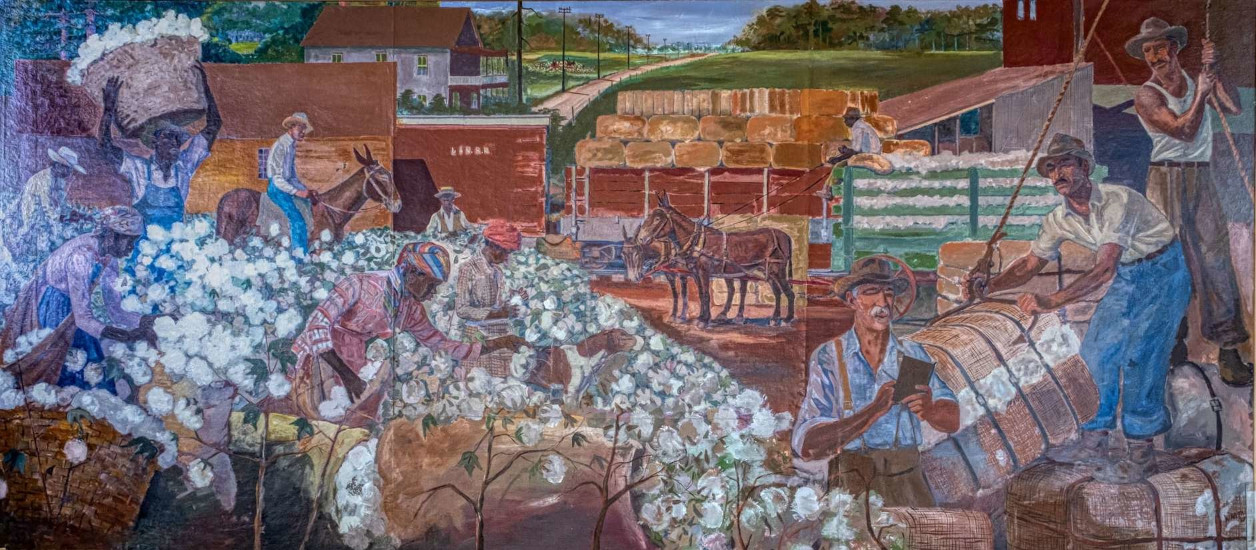

J. Kelly Fitzpatrick, best known for his paintings of rural Alabama, was commissioned to by the federal government as part of the Public Works of Art Project to produce paintings, including murals inside the newly constructed post offices in the towns of Ozark, Alabama and in Phenix City, Alabama. The Phenix City Post Office is now used as the public library. It houses the mural Cotton.

Cotton by J. Kelly Fitzpatrick, Phenix City Post Office, Phenix, City, Alabama.

Tuskegee, Alabama

This is another WPA, New Deal art project that is housed in the Tuskegee Post Office. It is titled The Road to Tuskegee. It is an oil on canvas by Anne Goldthwaite painted in 1937.

Cotton by J. Kelly Fitzpatrick, Phenix City Post Office, Phenix, City, Alabama.

They Met the Challenge pays tribute to the Tuskegee Airmen and their message of perseverance to rise above adversity, racism, and unfair training and performance expectations in the US Armed Forces. The mural was created by artist Marcus Akinlana. Elements of the design were inspired by the Tuskegee Airmen’s accounts of their boyhood dreams of learning how to fly. The bas-relief sculptures which embellish the mural were created by students in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania at the Mural Arts Mural Academy. These students took part in a series of workshops with Akinlana.

The largest image is the head and goggles of a pilot in combat. Inside the goggles on the left is the image of Alfred Anderson, the airmen’s pilot trainer. On the right is a boy holding a model airplane representing the yearning to become a pilot. At the top, a Red Tail fighter squadron achieves a successful mission escorting bombers. The pilot in the P51 Mustang is firing bullets into a Nazi ME-109. Medals of Honor border the main action. Also included are eight (8) Philadelphia Tuskegee Airmen painted as they looked in their younger years, female parachute riggers, mechanics, and the historic army airfield training building.

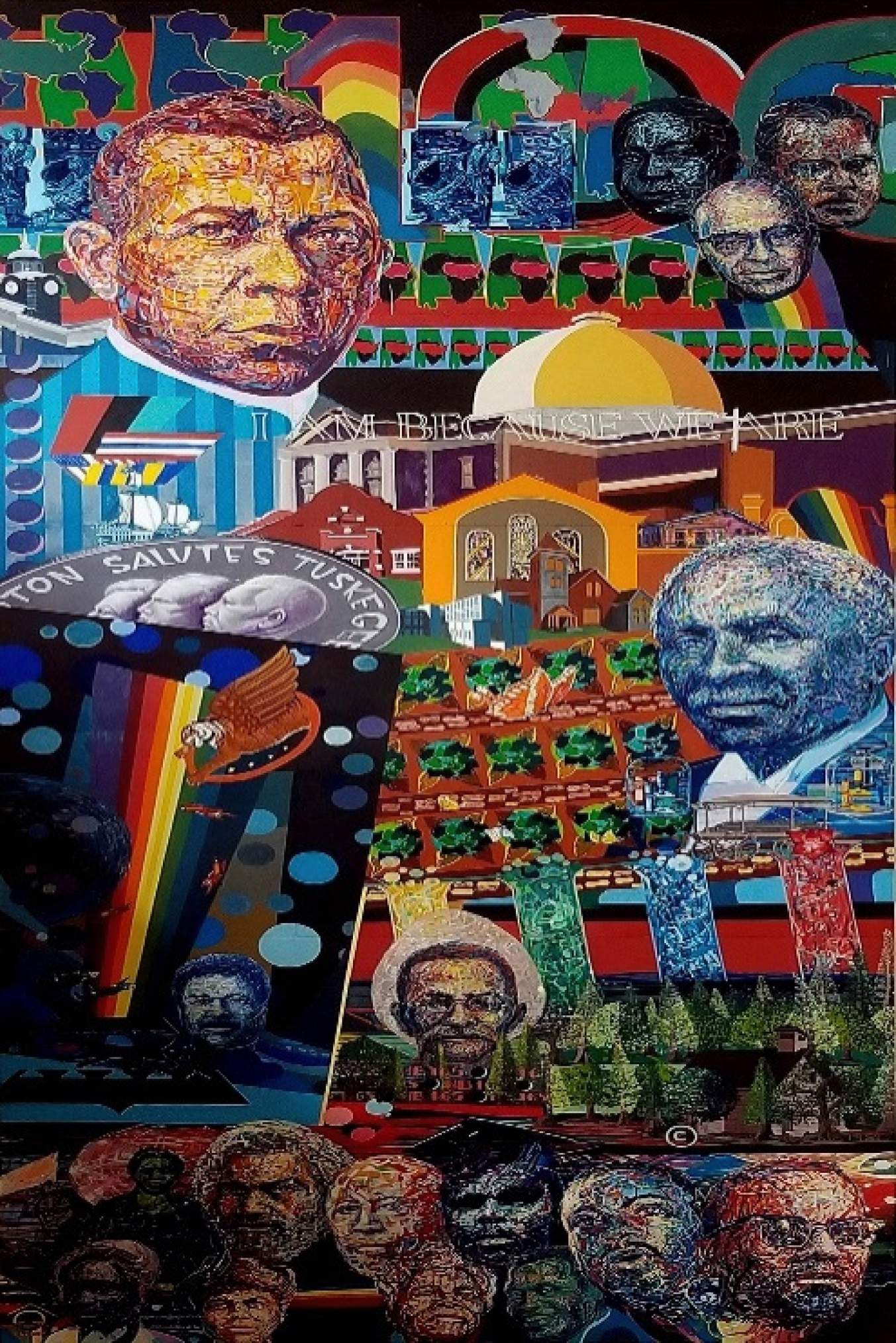

Centennial Vision

On the anniversary of the founding of the Tuskegee Institute in 1980, the artist Nelson Stevens created the above mural entitled Centennial Vision to celebrate the occasion. Although Stevens was commonly an exterior mural painter, he created this mural on the inside of the Tuskegee University Administration Building. The mural contains the images of African American notables such as Booker T. Washington (the first president of Tuskegee), General Chappie James and the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II, Cinque, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and George Washington Carver, as well as the antislavery figures Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglass. Also included in the image is a phrase made famous by the African scholar John S. Mbiti, “I Am Because We Are.”

Selma, Alabama

Never Forget-Never Again, on the Ancient Africa, Enslavement, and Civil War Museum, in Selma. Artist Unknown.

The Civil Rights Memorial Mural on the side of a building near the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Selma, Alabama by the Liberation Summer Project Class of 1999, Courtney Snelling, Ellyn Jackson, Lovineeha Gooch, and Naijal Abdul.

In conjunction with the National Voting Rights Museum in Selma is the Civil Rights Memorial Mural. The mural is in a small park at the southern end of the landmark Edmund Pettus Bridge. The center of the mural features Martin Luther King Jr. with the Pettus Bridge. The lives depicted in the mural are: Jonathan Daniels (1939-1965); killed on August 20, 1965 after being released from jail for participating in a demonstration in Fort Deposit on August 14; Viola Gregg Liuzzo (1925-1965); shot to death in her car on the last night of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March; Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968); assassinated on April 4, 1968, the day after supporting striking sanitation workers in Memphis; Rev. James Reeb (1927-1965); died on March 11, 1965 in Selma, after being attacked by a group of white supremacists and; Jimmie Lee Jackson (1938-1965); a Vietnam war veteran who was shot twice in the abdomen by an Alabama state trooper on February 18, 1965 in Marion, Alabama and succumbed to his wounds eight days later.

Union Springs, Alabama

Across the state in the small town of Union Springs (Bullock County) is the wonderful mural of singer Eddie Kendricks, the first lead tenor for The Temptations, who was born there on December 17, 1939. The group was formed in Detroit, under the Motown Records label. The group’s original lineup featured three Alabama natives – Kendricks, Paul Williams, and Melvin Franklin. They became one of the most successful musical acts in history. Throughout their career, the group released 14 Billboard R&B No.1 singles, such as classics Just My Imagination (Running Away with Me) and My Girl, and won three Grammy Awards. Kendricks also released two No. 1 R&B singles as a solo artist – Boogie Down and Keep on Truckin’. Kendricks and The Temptations were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1989. (Graydon Rust, Alabama 200)

Montgomery, Alabama

The Alabama capital city maintains an important place in the history of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s. It was here in Montgomery that Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus and was arrested.

It was here that the third and final voting rights March from Selma in 1965 ended on the steps of the state capitol. Montgomery artist Sunny Paulk created the commemorative mural, as a tribute to the Selma-to-Montgomery march. It portrays the memorable scene of marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The mural is located just a few blocks from the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice — the nation’s first memorial dedicated to observing the legacy of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow.

A Mighty Walk. Photo courtesy of Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts.

Titled Unforgettable, Montgomery’s mural showcasing Montgomery native Nat King Cole’s life and legacy painted by Zoe Hall for The Bama Buzz.

Anniston Murals and Civil Rights and Heritage Trail

Moving northward to Anniston, Alabama lies pivotal historical moments during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, including the Freedom Riders stops.

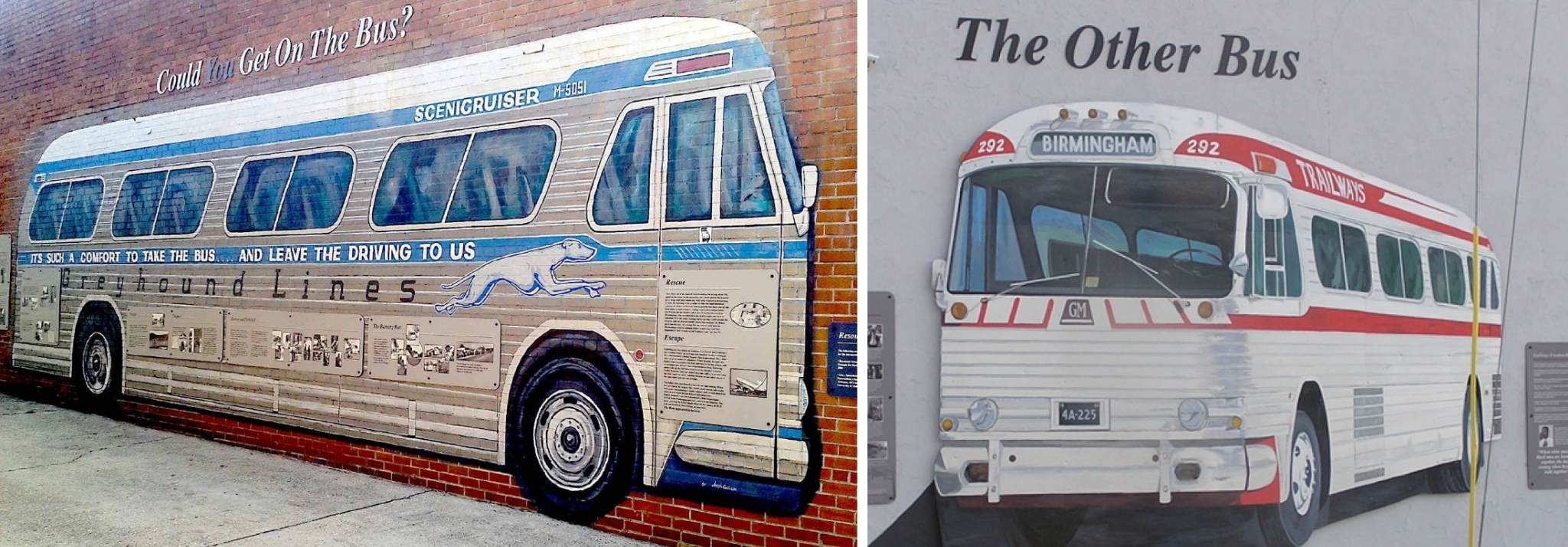

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated South in 1961 and ensuing years to challenge the non-enforcement of the U.S. Supreme Court decisions of Morgan v. Virginia (1946) and Boynton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Southern states had ignored the rulings and the federal government did nothing to enforce them. The first Freedom Ride left Washington, D.C. on May 4, 1961, and was scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17.

On Sunday, May 14, 1961, Mother’s Day, in Anniston, Alabama, a mob of Klansmen, some still in church attire, attacked the first of the two Greyhound buses of Freedom Riders. The driver tried to leave the station, but he was blocked until KKK members slashed the tires of the bus. The mob forced the crippled bus to stop several miles outside town and then threw a firebomb into it. As the bus burned, the mob held the doors shut, intending to burn the riders to death. Sources disagree, but either an exploding fuel tank or an undercover state investigator who was brandishing a revolver caused the mob to retreat, and the riders escaped the bus. The mob beat the riders after they got out. Warning shots which were fired into the air by highway patrolmen were the only thing which prevented the riders from being lynched. The roadside site in Anniston and the downtown Greyhound station were preserved as part of the Freedom Riders National Monument in 2017.

A second bus which pulled into the Anniston Bus Terminal an hour after the Greyhound bus was burned was a Trailways bus. It was boarded by eight Klansmen who beat the Freedom Riders on it and left them semi-conscious in the back of the bus.

The Greyhound bus mural is painted in the actual spot where the assaults began. Both spots are now on the Anniston Civil Rights and Heritage Trail.

Situated within an area in west Anniston is a park known as The Sacred Place. It was created with a great intent to spotlight Anniston’s African American history, and to serve as a means for residents and visitors alike to connect, or reconnect, with the stories of the community as it used to be and reflect on the progress that has been made since then. The site presents an important avenue for people to learn about the unity fostered by the civil rights movement and take those lessons into their lives today. In 1991 The Sacred Place was added to the National Registry of Historic Places.

There are future mural sites to be added on the Anniston Civil Rights and Heritage Trail. It’s truly a stop worth visiting in Alabama.

Anniston: A City Within a City mural nestled in the Sacred Place by artist John Davis.

Talladega, Alabama

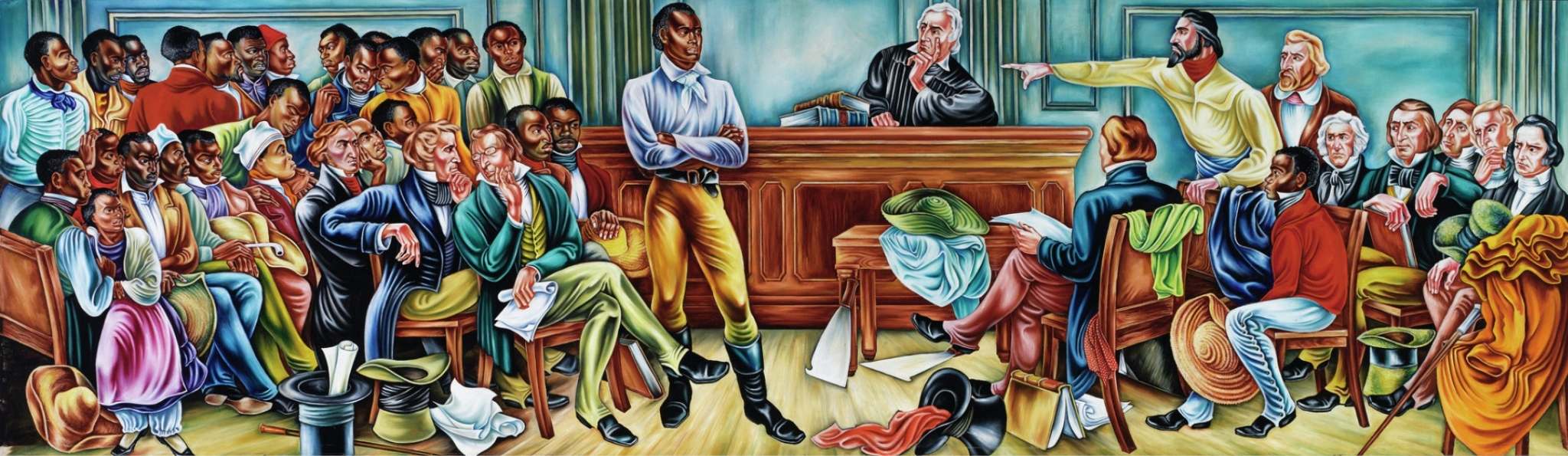

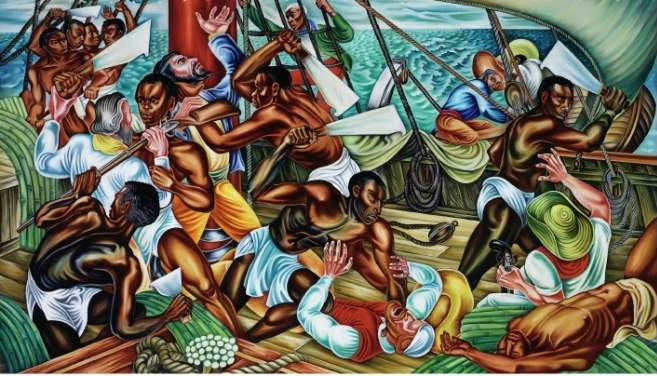

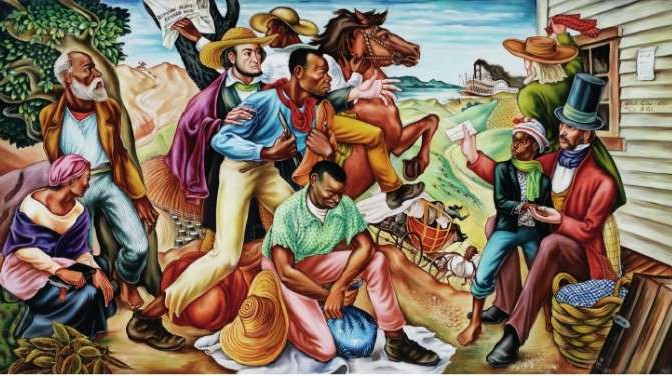

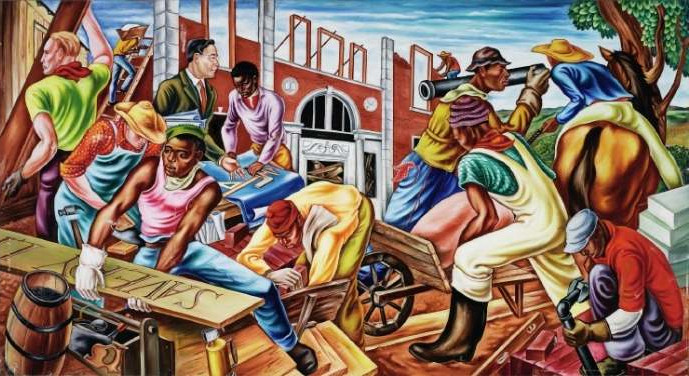

Most Americans know little about the painter Hale Woodruff, but he had a profound influence on 20th century American art. Woodruff was commissioned to paint the Amistad Murals in 1938. With powerful murals, Woodruff paved the way for African American artists.

Today, Woodruff is best-known for a set of murals at Talladega College in Alabama. The giant paintings are in vibrant colors with nearly life-sized figures. On one wall, the slave mutiny on the Amistad ship is depicted. On another wall, there’s an urgent scene in the woods, as slaves are about to cross the Ohio River to freedom. In another mural, the trial of the Amistad mutineers, is a man in a green shirt in the crowd. It’s a self-portrait of Woodruff himself. He always placed his image in his works.

In this 1939 mural, artist Hale Woodruff depicts the trial of the Africans aboard the Amistad.

The slave mutiny aboard the Amistad

Slaves about to cross the Ohio River to freedom, c. 1939

The Building of Savery Library, 1942.

All by Hale Aspacio Woodruff (August 26, 1900–September 6, 1980) Image: Peter Harholdt/Collection of Talladega College, Talladega, Alabama. Copyright Talladega College

The Amistad Murals, worth about $50 million, are in the Dr. William Harvey Museum of Art at Talladega College. Other murals in the collection depict the Underground Railroad and even the opening day at Talladega College.

Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham, nicknamed the Magic City, boasts an impressive collection of historical murals and artful street décor painted on buildings throughout the city. Some are even painted on plywood in the downtown area. Thanks to local artists and artists’ collectives, Birmingham is quickly becoming a hotspot for creative and colorful street art.

On 41st Street, right in the heart of Avondale is this mural featuring four Birmingham icons: civil rights activist Fred Shuttlesworth; iconic jazz musician Sun Ra; activist Angela Davis; and photo journalist Spider Martin. It reminds us of the powerful forces from the Magic City.

Know Your History, by artist Tim Kerr.

Just a short walk-through downtown Birmingham one would be astonished at the murals that describe not just Birmingham’s African American history and events, but also the history of the state of Alabama. From chaos that has plagued the Magic City and the state comes impressive artwork and murals.

Local artist Andy Jordan works on a painting of Cudjo Lewis (above), who was among the last survivors of the slave trade. He was brought to the Alabama coast in 1860 on the slave ship Clotilda. (Source: Tom Gordon)

The above mural commissioned by Wells Fargo Bank depicts the 50th Anniversary of the Voting Rights Act. It is located at 316 18th Street South.

Birmingham has no shortage of amazing murals. Across the metropolitan area, you will find buildings carefully crafted with bright colors, encouraging messages and unmatched artistic talent.

One of the most gorgeous murals is in the West End community in Birmingham, encouraging us to “Find Your Magic” in The Magic City. This piece (below) was created by local talent Marcus Fetch, who is well known for his one-of-a-kind additions to the Birmingham mural scene.

Young Angela Davis, located 1531 12th Ct. North, Birmingham: Artist Unknown (Alabama Mural Trail Collection)

Dynamite Hill and Change Mural

Artists: G. Bodile Balams, Darryl Grant, Melissa King

George Floyd, Downtown Birmingham, by Shane Bansa

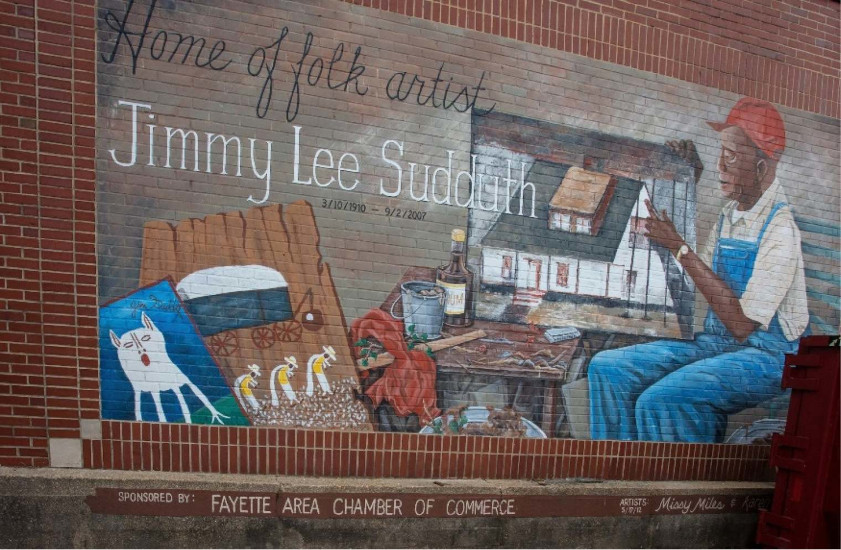

Fayette, Alabama

Outsider artist Jimmy Lee Sudduth was born in Caines Ridge, near Fayette. He was a self-taught artist who is best known for creating finger paintings out of mud and other natural pigments on a variety of salvaged surfaces such as plywood boards, doors, and roofing shingles. Sudduth spent almost his entire life in an unpretentious home in Fayette. Sudduth’s portraits and depictions of the rural South earned him international recognition. He won the 2005 Alabama Governor’s Arts Award, and his paintings are on display in the permanent collections of the Fayette Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts.

Hartselle, Alabama

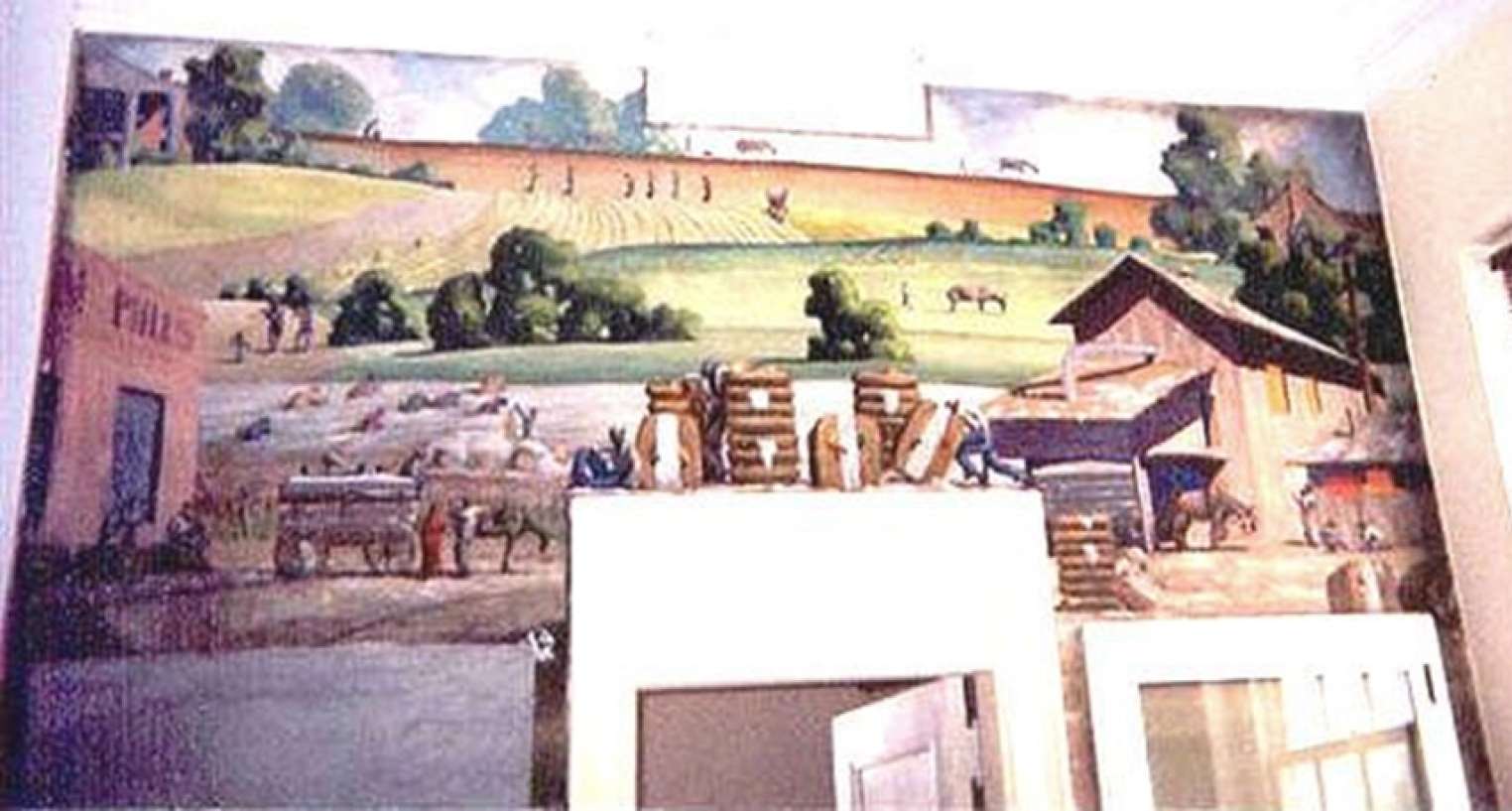

Cotton Scene by Lee R. Warthen, 1941, now hangs in the Hartselle Chamber of Commerce offices, which are housed in the historic depot. It is a WPA federal arts piece. (Source: Jimmy Emerson)

Huntsville, Alabama

The murals in Huntsville are part of the North Alabama Mural Trail. The North Alabama Mural Trail encourages residents and visitors alike to travel across the region to view remarkable street art paintings while learning about the history of the city in an artistic way.

Huntsville celebrated the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with a beautiful 3-story mural. The mural, by Nashville-based artist Kimberly Radford, celebrates women’s suffrage with a young African American girl reaching high to water a nearby tree growing on Washington Street.

Wahlburgers at Huntsville’s Mid-City District showcases a huge mural of Little Richard painted by artist Logan Tanner. Little Richard left stardom to attend the nearby Oakwood College (now Oakwood University) in 1957. After passing away in May 2020, he was buried at Oakwood Memorial Gardens Cemetery.

The Clinton Row Colorwalk (above) is an alley filled with murals painted by local artists in Huntsville.

Space is Our Place by Jahni the Artist is part of a mural collaboration between Arts Huntsville and Google Fiber.

The Alabama African American Mural Trail offers a diverse set of wall painting in urban and rural areas traversing the state. The trail in article is not exhaustive. People who follow the trail will find illustrations and descriptions of Alabama’s history and cultural attractions ranging from the Civil Rights Movement to Alabama’s contributions to space. The path to visit each one encourages all to discover not only the urban and rural Alabama but “off the beaten path” communities in and around the state. Discover Alabama’s heritage, splendor, and love of the arts through these beautiful, impressive paintings around our great state.