By Nettie Carson Mullins

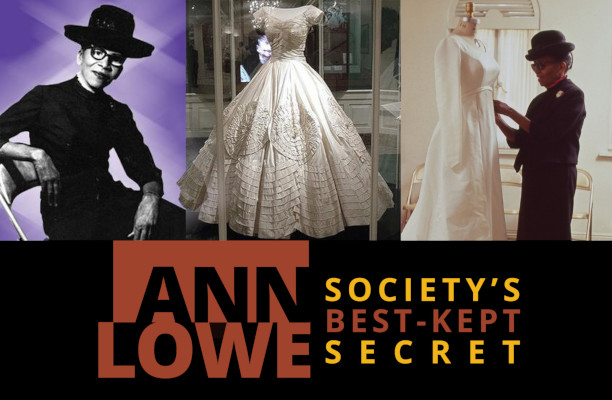

“Society’s Best-Kept Secret!”

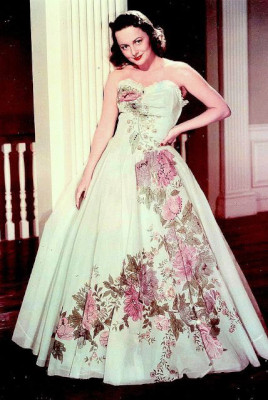

In 1964 this is how The Saturday Evening Post referred to fashion designer Ann Lowe. Even though Ann Lowe had been designing couture-quality gowns for America’s most renowned debutantes, heiresses, actresses, and high society brides—including Jacqueline Kennedy, Olivia de Havilland, and Marjorie Merriweather Post—for decades, she remained virtually unknown to the broader public.

Considered one of America’s most significant designers, Ann Lowe was born in Clayton, Alabama, around 1898 and reared in Montgomery. Her grandmother Georgia Thompkins and mother Janie Cole Lowe were domestic slaves in Alabama in the 1850s. Ann’s grandfather, General Cole, a freeman carpenter, purchased and gained Janie and Georgia’s freedom in 1860.

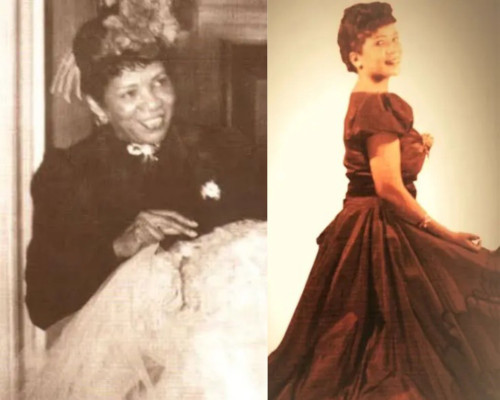

Her mother and grandmother were skilled dressmakers who sewed for wealthy white families in the state, and they taught Ann to sew as early as age five. By the time she was six, she had developed a love for using scraps of fabric to make small decorative flowers patterned after the flowers she saw in the family’s garden. This childhood pastime would later become the signature feature on many of her dresses and gowns. By age 10, she was making her own dress patterns.

It is significant to note that the period from the 1880s to the mid-1900s was the height of the Jim Crow era in the South. Ann, her mother, and her grandmother were building up a business during this era that served an elite white clientele. Dressmaking was some of the highest-paid, most respectable work that women, Black or white, in the 19th century could engage in.

In 1916, a chance encounter in a department store with influential Tampa, Florida socialite Josephine Edwards Lee changed Lowe’s life. Mrs. Lee observed that Lowe’s outfit was very stylish and exceptionally well-made. Lowe informed her that she made the ensemble, which prompted Lee to invite Lowe to Florida as her live-in dressmaker and to make the bridal gowns and trousseau for her twin daughters.

After discussing the offer with her husband, who wanted her to remain a housewife, Lowe accepted the offer and moved with her son to the Lee family estate at Lake Thonotosassa in Tampa, Florida. She felt it was a chance to make all the lovely gowns she’d always dreamed of. In Tampa, she developed a list of loyal clients and supporters.

While reading a fashion magazine, Lowe, who was eager to enhance her skills, learned about the S.T. Taylor School of Design in New York City. With Mrs. Lee’s encouragement, she applied for admission and was accepted. When Lowe moved to New York to enroll at S. T. Taylor Design School in 1917, the school’s administration didn’t realize that she was Black until she showed up on the first day. And to appease the majority white people in this institution, she was seated away from other students in another classroom. Very quickly, she was noticed by her instructor because she was doing such great impeccable work. Her instructor would take her work and show it as a great example to the other students. Before she knew it, the students would be hanging around the doorway, looking at what she was doing. Hence, she graduated in half the time.

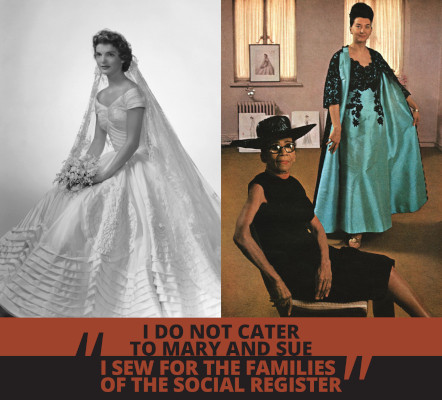

Lowe began designing for socialites, including famous families like the Rockefellers and the DuPonts. Alexandra Deutsch, the Winterthur Fashion Museum’s Director of Collections, notes that her “meticulous handwork and sculptural fabric flowers…made her gowns instantly recognizable status symbols for society women.” Lowe was proud of her connections to high society, telling Ebony Magazine: “I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register.”

Ann Lowe returned to Tampa at a time when there were growing demands for ball gowns, cotillion wear, and other formal attire. To respond to those needs, she hired and trained 18 seamstresses and opened her own shop, the Annie Cone Boutique.

Lowe long desired to establish her own salon in New York, where she could make beautiful, custom gowns for women listed on the Social Registry. So, in 1928 Lowe closed the Annie Cone boutique and permanently moved to New York, where she continued to design for elite women and their families.

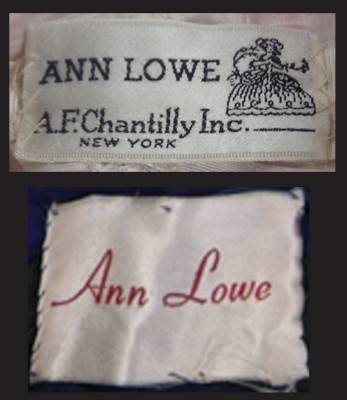

Ann Lowe owned and operated several shops in New York over the course of her life, including Ann Lowe Inc. on Madison Avenue during the late 1940s and early 1950s; Ann Lowe Gowns on Lexington Avenue in 1955; A.F. Chantilly Inc. on Madison Avenue in 1965; and Ann Lowe Originals in Manhattan on Madison Avenue in 1968 until she retired in 1972. The Madison Avenue locations solidified Ann as the first African American to have a shop on the famed fashion retail strip, and it verified her significance as an American couturier of note.

The 1950s marked a significant turning point in Ann’s life and career. She opened Ann Lowe Inc. with business partner Grace Stelhi, wife of the owner of Stelhi Silks located on Madison Avenue. She was the first African American to own a couture salon on this fashionable street. By the end of 1953, the partnership had ended, and Lowe’s son, Arthur Lee, joined her as her bookkeeper and supply manager.

Lowe’s fairytale-like gowns appeared in Vogue and Vanity Fair magazines. Her creations were respected by renowned designers such as Christian Dior and Edith Head, and she earned key commissions and obtained a greater geographical exposure from high-end luxury department stores such as Montaldo’s, Neiman Marcus, and I. Magnin.

Ann Lowe’s most historically significant assignment was the bridal gown and bridal party dresses for the 1953 wedding of Jacqueline Bouvier and then-Senator John F. Kennedy, who would become president of the United States in 1961. About 10 days before the wedding, a ruptured pipe in Lowe’s building destroyed the wedding gown and 10 of the 15 bridesmaid’s dresses. Ann and her team of seamstresses recreated the dresses, but she ultimately sustained a $2,200 loss in income. She never reported the loss to the Kennedy family.

While there were many highs during this period, there were an equal number of lows for Lowe. In 1958, her son Arthur Lee was killed in a car accident. The tragic loss marked an overall decline in her financial stability, her health, and eventually her career. Ann’s eyesight in her right eye began failing because of glaucoma. Increasing tax debts forced her to close her business in 1960.

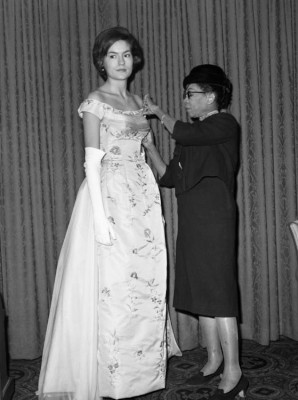

Right: Ann Lowe, in her New York salon with London model Judith Palmer, photographed for the December 1966 edition of Ebony magazine. (Moneta Sleet, Jr./Johnson Archives; NY Post)

In 1960, Saks Fifth Avenue was one of the leading American luxury department stores that specialized in debutante and wedding gowns for elite women in the country. In 1956, Saks dedicated a space for exclusive services for these customers. Mrs. Edward Ewen Conner, the founding manager, named the space The Adam Room, in honor of Adam Gimbel, the head of Saks.

Saks invited Ann to work in The Adam Room shortly after her salon closed. The offer, a prestigious connection for Lowe, came with some fanfare. Saks’s official ad, with a silhouette of Ann Lowe, publicized the business arrangement, declaring, “Saks Fifth Avenue takes pride in announcing that the Debut and Bridal Gown Collection created by Ann Lowe can now be found exclusively in The Adam Room.”

The contract was extremely uneven and not to Lowe’s advantage. In exchange for a workroom, she brought with her a sought-after list of select clients. She had to purchase her own supplies and fabrics, which were of the highest quality, and she had to pay her staff. Saks even set the final sale prices for her garments. In the end, Lowe was paid considerably less than the labor and materials she put into the dresses. By the time she realized the extent of her losses, she was deep in debt. In 1962, she left Saks and opened a smaller workshop.

By 1962 Ann had mounting debts. The U.S. Department of Revenue closed Lowe’s New York shop due to $12,800 owed in back taxes. She believed the debt was later paid by Jacqueline Kennedy. She stated, “One morning, I woke up owing $10,000 to suppliers and $12,800 in back Taxes. Friends at Henri Bendel and Neiman-Marcus loaned me money to stay open, but the Internal Revenue agents finally closed me up for non-payment of taxes. At my wits end, I ran sobbing into the streets.”

To make things worse, the glaucoma resulted in the removal of Lowe’s right eye, even as she was experiencing cataracts in the other eye. After the foreclosure of her salon, Lowe began working for Madeleine Couture on Madison Avenue from 1962 to 1965.

From 1968 and 1972, Lowe opened and operated the Ann Lowe Originals Shop on Madison Avenue until she retired. At that time, she moved to Queens, New York to live with Ruth Alexander, who formerly worked in Lowe’s salon and whom she identified as her adopted daughter.

On February 25, 1981, Ann Lowe passed away in Queens.

- Major, Gerri (December 1966).“Dean Of American Designers”.

Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. 22 (2). - Way, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe: Recovering an African American Fashion Legacy That Clothed the American Elite.”

Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, vol. 19, no. 1, Feb.

2015, pp. 115–141. - Why Jackie Kennedy’s Wedding Dress Designer Was Fashion’s ‘Best Kept Secret’. New York Post. October 16, 2016.

- Alleyne, Allyssia (23 December 2020). “The Untold Story Of Ann Lowe, The Black Designer Behind Jackie Kennedy’s Wedding Dress”. CNN.

- New Exhibit Showcases the Creations of Forgotten Fashion Designer Ann Lowe.

https://www.cbsnews.com/video/new-exhibit-showcases-the-creations-of-forgotten-fashion-designer-anne-lowe/ - Ann Lowe on the Mike Douglas Show, 1965

https://nmaahc.si.edu/biography/ann-lowe