By Guy Trammell

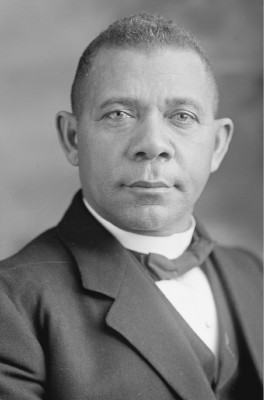

In 1881, Booker T. Washington built Tuskegee Institute on an abandoned plantation.

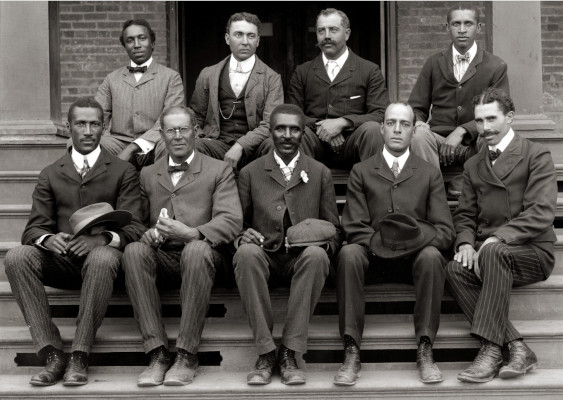

His Hampton Institute roommate, Charles W. Green, became agriculture director (before George Washington Carver arrived in 1896). In 1890, Green built a home in a wooded area west of the campus. Graduates and faculty followed him, and Booker T. Washington named the settlement the “Village of Greenwood” to honor Green. This all African American community grew and thrived in the midst of Jim Crow.

The community was advanced in technology. Alabama Power was established in December, 1906. Greenwood had the world’s first African American-owned and operated electric company in the 1890’s. Greenwood sold electric power to Tuskegee’s white businesses and homes.

It also had a telephone exchange. This produced the first Black telephone operator, Ophelia Cooper, and she trained other Black operators. Greenwood’s streets were named after Washington’s inner circle, including Clark Avenue, for Jane E. Clark, his Dean of Women. These dirt streets had sidewalks, steps, curbing and street lights. The homes had indoor plumbing, electricity and many had a piano.

The Institute’s 47 trades made Greenwood a self-sufficient community. Local services available were: locksmithing, tailoring, upholstery, typewriter repair and sewing machine repair. Manufacturing included: canning, furniture making, and book printing. The Tuskegee train ran from Greenwood to the Chehaw West Point railroad depot, carrying products across the country. One year’s receipts showed 14,000 passenger tickets sold.

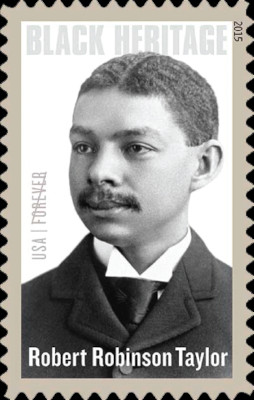

Tuskegee Savings and Loan, and Tuskegee Federal Credit Union were created to assist residents in purchasing property. The homes and buildings were designed and constructed by African American residents, including Robert R. Taylor, the first Black graduate from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He formed the first African American architectural firm with Louis Persley.

Greenwood had every denomination of church, it’s own school system, nursery to college, and one of Alabama’s largest libraries. Except for the Catholic priest and nuns, all business owners, teachers, pastors and contractors were African American. From laundries, clothing and shoe shops, to groceries, restaurants, cafes and night spots, the community had it all. Greenwood’s Poolville Motel, with its cottages, restaurant and nightclub, was listed in The Green Book.

With Alabama public parks closed to Blacks, residents created private lake recreation areas, for family and church cookouts. Community teams competed on Greenwood’s golf course and 14 lighted tennis courts. The Lincoln Drive-In showed movies, and concerts were on campus. Greenwood parents created the Carver Boy and Girl Scout District, and built Camp Atkins, one of the first Black Scout camps. It had a mess hall, three cabins, hiking trails, and a six-acre lake, on 200-plus acres of forest. It was regularly attended by scouts from surrounding states.

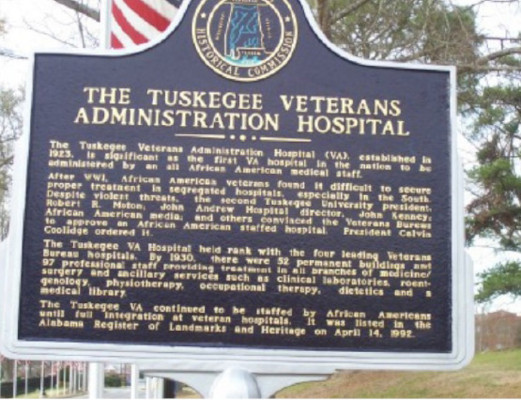

Greenwood had the only African American staffed and administered United States veterans hospital, as well as Alabama’s first African American hospital, John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, the first full-service U.S. hospital for African Americans, which in 1937 created the world’s first children’s polio center. Medical services were provided only by African American professionals, who were the best in the medical field at that time. Many were pioneers, such as Dr. Charles Drew, creator of blood banks, and Dr. Raymond R. Adams.

There was also the only HBCU College of Veterinary Medicine, with it’s small and large animal hospitals. Most of the children never had a white physician or white teacher. The only professionals and people in leadership, they saw, were African American.

In July 1923, 700 Ku Klux Klan members burned a 40-foot cross on the town square, then marched to destroy Tuskegee Institute and Greenwood. They wanted to stop the hiring of an all African American staff at the recently constructed Tuskegee Veterans Hospital. Their plans ended abruptly when they were greeted by a few thousand people that arrived the day before to protect the community that Booker T. Washington built. There were also students, with guns from the school armory, in trees along the route the Klan had to walk. Another thousand supporters were waiting in the football stadium to provide backup. The people were organized by the instructor of Cadets, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., who became the first Black U.S. General. The Klan tried many times to burn down Greenwood, however, the African American men were organized, armed and ready to defend the community, which put fear in the Klan. In the 1960’s, White law enforcement officers, chasing Civil Rights workers, would not enter Greenwood.

The community was never incorporated, however, Greenwood annually elected a governing council, and annual dues were collected for community maintenance, From 1890 till 1967, Greenwood never had a police or law enforcement presence. This changed when Lucius Amerson was elected the first Black United States Sheriff since Reconstruction.

Greenwood’s Frazier Chevrolet Olds was the first African American car dealership in the South, from Maryland to California. A person could live in the Village of Greenwood for years without ever having to leave. There were service stations, with automotive repair. Holland’s Appliances and Allen’s Variety were the department stores.

The entire community, with it’s subdivisions, is about five square miles. Many Tuskegee Airmen settled there. Booker T. Washington saw Greenwood as a model for what Black people could do anywhere. He spoke about it on his 1905 tour of Arkansas and Oklahoma. A newly-arrived Black land developer named Ottawa Gurley was in the Tulsa audience. This inspired Gurley the next year to purchase land, north of the railroad, and build Tulsa’s Greenwood community. Booker T. Washington later named it “Negro Wall Street”. It is now known as “Black Wall Street”.