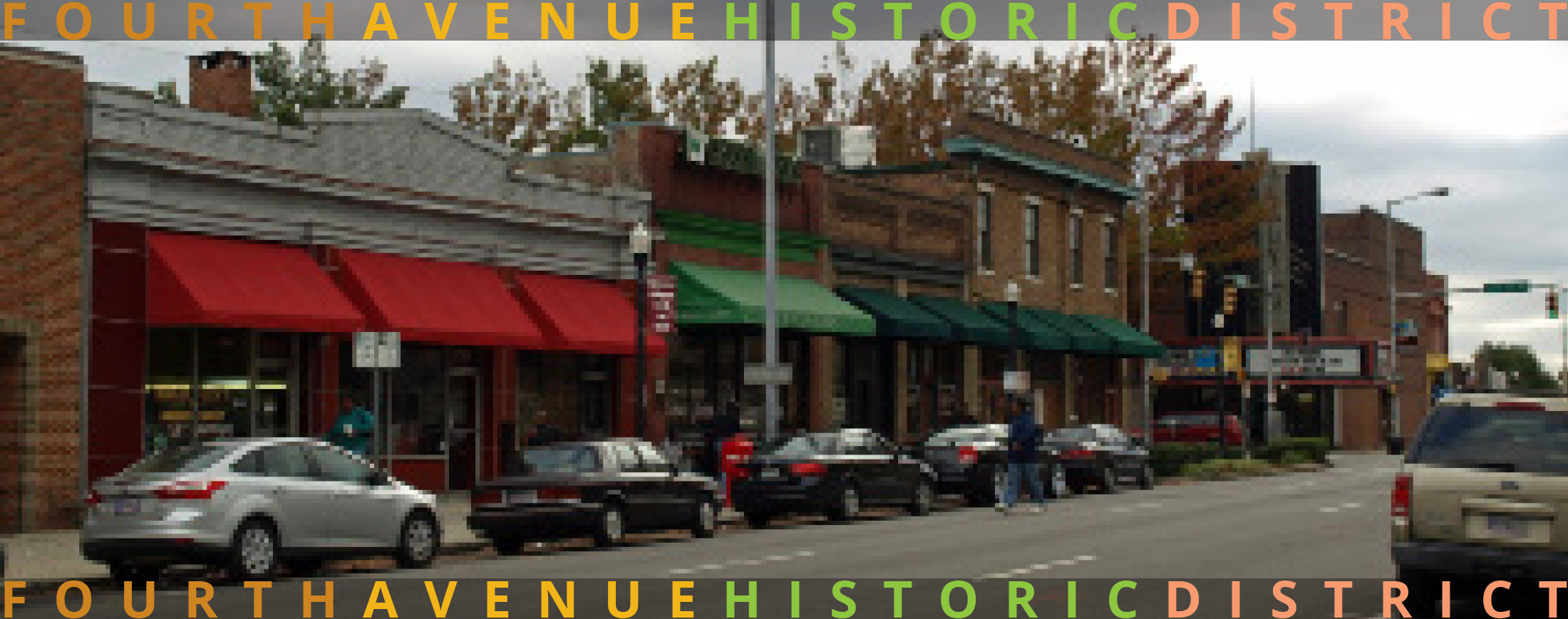

Fourth Avenue North, Birmingham, Ala., circa 1930s.

Prior to 1900 a “black business district” did not exist in the city of Birmingham. In a pattern characteristic of Southern cities founded during Reconstruction, Black businesses developed alongside those of Whites in many sections of the downtown area.

After the turn of the century, Jim Crow laws authorizing the distinct separation of “the races” and subsequent restrictions placed on Black firms forced the growing Black business community into an area along Third, Fourth and Fifth Avenues North from 15th to 18th Streets. Segregation and discrimination created a small world in which Black enterprise was accepted and to which Blacks had open access.

This area served as the business, social and cultural center for Blacks with activities similar to those in the predominantly White districts. The businesses located in the area included barber and beauty shops, mortuaries, saloons, restaurants, theaters, photographic studios and motels. These Black businesses and their successors continued to do well throughout the 1960’s.

The Black business district was not only “alive” during the daylight hours but “thrived” throughout the night. On Friday and Saturday nights, the streets were filled with crowds of people visiting the bars or just out for a stroll. Live entertainment made the district “the place to be.” Monroe Kennedy, a blind bookie, made sure that Fourth Avenue got its fair share of the “Big Swing Bands.” Performers such as Duke Ellington, Lucky Millender, Claude Hopkins, Jimmy Lunceford, Sonny Blount (Sun Ra), Fess Whatley (Southland Greatest Swing Band) and Louis Armstrong were known to frequent the Masonic Temple at 1630 Fourth Avenue North.

This seven-story building was built in 1922.

Not only was the Masonic Temple used for entertainment, it housed Black professional offices and was the state headquarters for the Masons and the Order of the Eastern Star.

Masonic Temple, Birmingham, Ala. (National Park Service)

Masonic Temple, Birmingham, Ala. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

Other establishments located in the Fourth Avenue area included:

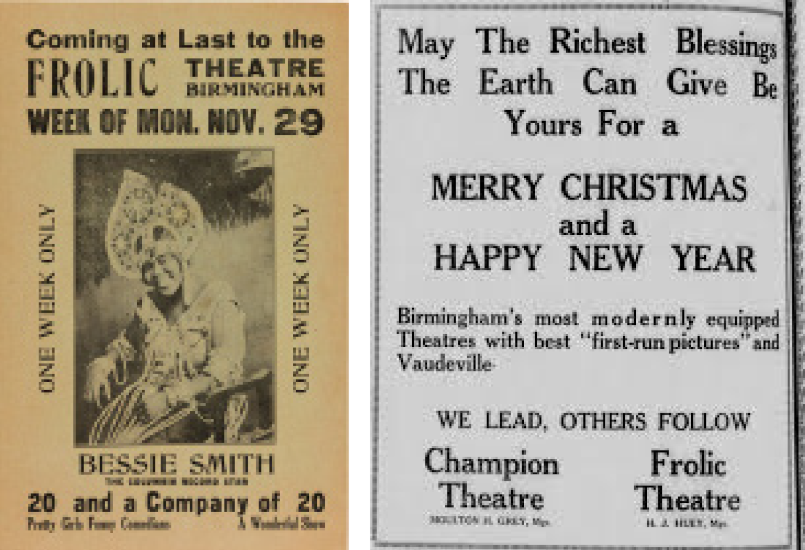

The Frolic Theatre

While other theaters provided movies, the Frolic under the management of Henry Hury, had live stage shows during the 1930’s. Not only did singers and dancers captivate the audiences, but live vaudeville shows came to the area: Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, Mamie Smith, Whitman Sisters, Butter Bean & Susie (Vaudeville show), Hot Harlem Review (first-class show out of New York), Leon Claxton’s Harlem in Havana Review just to name a few.

Courtesy Heritage Auctions

Bob’s Savoy, a famous night club/restaurant, entertained the elite of the Black athletic and entertainment world. People such as Willie Mays, Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson sometimes stopped by to talk to the owner, Bob Williams.

The Pantage, later renamed the Birmingham Theatre, was the Boutwell nee City Auditorium for the Black population. After entertaining the White citizens of Birmingham, performers like Nat “King” Cole would come to the Pantage and perform.

Another gathering place for Blacks was Brock Drug Store.

Robert “Bob” Williams, owner, Bob’s Savoy Restaurant (Chicago Defender)

The Pantage Theater, Birmingham, Ala. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library)

Beer glass from Bob’s Savoy restaurant. (Courtesy Burgin Mathews)

After the Civil Rights struggle, many new doors were opened literally and figuratively to Blacks. Many Black businesses, especially hotels and cafes suffered with the end of segregation. Once allowed into White establishments, sadly many Blacks did not return to the Black-owned businesses. The abandonment of black-owned businesses caused a major impact on the area, causing many to do their shopping in malls and other areas.

In 1979, the City of Birmingham elected its first Black mayor, Richard Arrington Jr. One of the many things on his agenda was the revitalization of this historic area of the city. In the early months of 1980, several business persons and city officials gathered in an effort to formulate a comprehensive funding proposal geared toward the city contracting a nonprofit organization to assist in the revitalization of the district.

Consequently, in July of 1980, the city contracted Urban Impact, Inc., to ensure improved business opportunities for socially and economically disadvantaged businesspersons and residents in the Fourth Avenue Business District.

It was identified that most merchants in the District were renting from absentee landlords. Therefore, Mayor Arrington, the Birmingham City Council and the board and staff of Urban Impact created incentive programs which would place merchants in ownership positions (Land Bank Program) and assist them in developing their property (Rebate Program).

These incentive programs enabled many merchants who were renting from absentee landlords to purchase their buildings. It also enabled them to complete inside and outside renovations.

In April 1982, Urban Impact was successful in getting the Fourth Avenue Business District nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. This nomination brought with it tax and investment advantages for businesses.