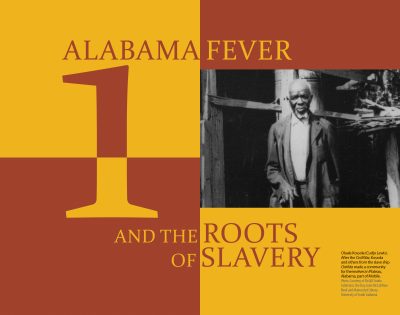

Alabama Fever and the Roots of Slavery

Respectfully submitted by: Dr. Felicia Bell, Rosa Parks Museum Troy University

Prior to the War of 1812, Native American tribes within the Creek Confederacy were the dominant demographic in the “Old Southwest.” Then, in 1814, General Andrew Jackson defeated the Creeks resulting in the acquisition of over 21 million acres of land. After decades of treaties, harassment by and resistance to land-hungry whites, and forced removal, Native Americans settled lands further westward—resulting in the expansion of slavery to the territories.

At the same time, the nation’s agricultural economy was changing. Tobacco planters in the Upper South had depleted the soil and converted their farms to grow various crops such as wheat and corn, creating a mixed-crop economy for the region. Also, these crops were less labor-intensive than tobacco resulting in a surplus of enslaved agricultural labor. After the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, processing short-staple cotton became quicker as the global demand for it became more profitable. As a result, states in the Lower South that had built their economies on indigo and rice began to develop a dependency on cotton as a single-crop economy for that region.

Since cotton cultivation exhausted the soil so rapidly, planters sought to establish the crop in the newly-acquired, more fertile western territories that would become Alabama and Mississippi (and later Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas). By 1817, tens of thousands of white southerners were drawn to the “Black Belt,” a term used to describe the richness of the soil in the region. This wave of westward migration and swift settlement was referred to as “Alabama Fever.” These eager white settlers brought the enslaved people they owned with them to clear the land, build their homes, and provide a resource for labor.

“King Cotton,” as the rapidly-growing economy in the burgeoning Deep South was known, attracted not only land speculators, but also slave traders who recognized a lucrative business opportunity in the domestic slave trade. The Constitution prohibited America’s participation in the Atlantic slave trade in 1808. So an internal system of slave trading flourished with slave pens nestled inconspicuously in urban hubs such as Richmond, Charleston, and New Orleans.

The surplus of enslaved labor in the Upper South was sold to prospective buyers in Alabama and the Deep South to labor on cotton plantations. It took weeks for coffles of twenty or more enslaved people marching for miles to reach Alabama. Traders used routes that included major corridors such as the Old Federal Road. By the mid 1800s, advancements in industrial technology such as rail lines (built by enslaved people) and steamboats were used to transport enslaved people to Alabama and other locations. Some trade routes were over waterways and companies like Franklin and Armfield of Alexandria, Virginia owned a fleet of vessels to move enslaved people to the Deep South. As the enslaved population grew, Alabama became a “slave society” with its economy, political structure, and culture committed to the institution of slavery.

Chapter 1 overview from The Future Emerges from the Past, Celebrating 200 Years of Alabama African American History & Culture.

Photo: Courtesy of McGill Studio Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.