by Dr. Martha V. Bouyer

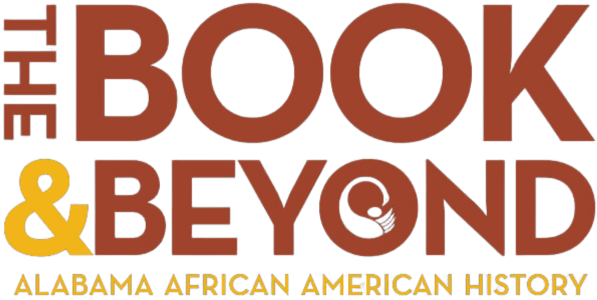

How Great Thou Art was Dr. Autherine Juanita Lucy Foster’s favorite hymn. The song expresses her love and adoration for God her Father. She loved to hear it sung and loved singing it.

Autherine Juanita Lucy was the 10th child of Milton Cornelius Lucy and Minnie Maud Hosea. The family owned and farmed 110 acres of land. In addition to farming, Mr. Lucy did work as a blacksmith, made baskets, ax handles, and other odd jobs to support his family.

At a time when few Blacks attended school on a regular basis because their labor was needed to help plant and harvest crops, Autherine was in school. During Jim Crow segregation she attended the local school through grade 10 because that is all that was available for Black students in Shiloh. Her parents sent her to Linden Academy where she completed her secondary education. This was a great sacrifice because Autherine boarded during the week and came home on the weekend.

After graduating from Linden Academy in 1947, Dr. Foster attended Selma University in Selma, Alabama, where she earned a teaching certificate. Because of changes in Alabama Law regarding teacher certification that formerly allowed a person with two years of college to teach school, Dr. Foster enrolled at Miles College in Fairfield, Alabama where she earned a Bachelor’s Degree in English.

After graduating from Linden Academy in 1947, Dr. Foster attended Selma University in Selma, Alabama, where she earned a teaching certificate. Because of changes in Alabama Law regarding teacher certification that formerly allowed a person with two years of college to teach school, Dr. Foster enrolled at Miles College in Fairfield, Alabama where she earned a Bachelor’s Degree in English.

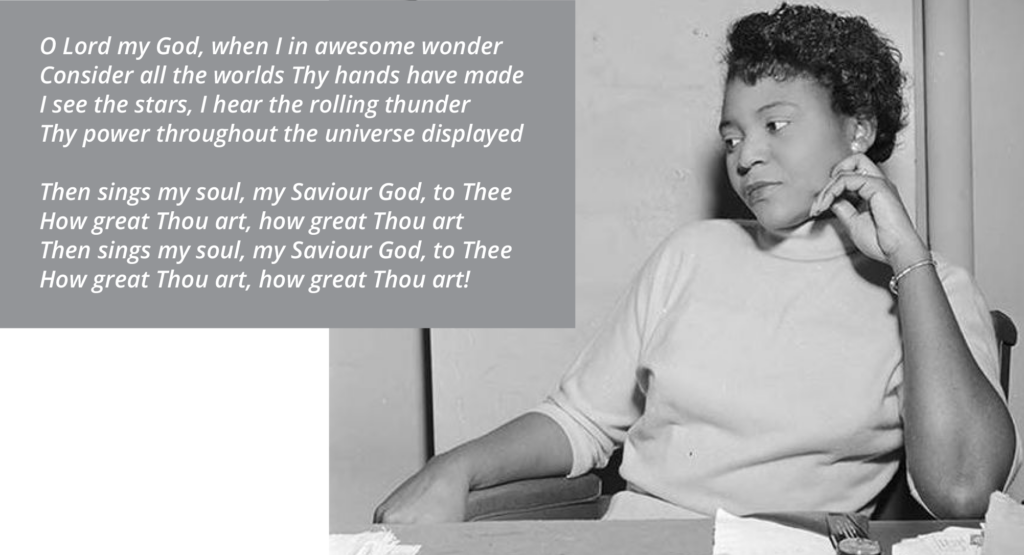

In 1952, after graduating from Miles College, Pollie Anne Myers a community activist and a friend of Dr. Foster’s, suggested that they enroll at the University of Alabama to earn master’s degrees. Dr. Foster agreed and the women filled out and mailed their applications for admission to the Registrar’s Office. She always wanted to be a teacher and was viewed by many as a Master Teacher.

Above: Autherine Lucy’s application to the University of Alabama.

The ladies submitted their applications for admission and received notification on September 18, 1952, that they had been accepted and even assigned to a dormitory.

The very next day, they received letters notifying them that they would not be able to attend the University of Alabama. There was no explanation given. People try to say that the University did not know the women were Black. (See a copy of Dr. Foster’s original application at left). There is no doubt regarding her race or education prior to applying to Alabama.

Fearing that they would not be admitted, they had already hired a local Birmingham civil rights attorney, Arthur Shores, to represent them. Over the next three years, the women would continue their efforts to enroll at UA. Mr. Shores would be joined in this struggle for equality by Thurgood Marshall and Constance Baker Motley.

Above: Autherine Lucy, center, confers with attorney Arthur Shores and Ruby Hurley of the NAACP. (AP)

Above: Autherine Lucy leaving federal court in Birmingham with attorneys Thurgood Marshall, center, and Arthur Shores. (AL.com)

While the case made its way through the courts another case, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, took center stage regarding the issue of equal education. The effort to provide equal educational opportunities to all students started as far back as the mid 1800’s. The lead attorney in the Brown case was none other than Thurgood Marshall who would go on to become the first African American to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court. (Please see the “Additional Resources” section for more on the Brown Case)

The Brown case was the proverbial “handwriting on the wall” for all states trying to enforce segregation in education. In preparation for the court battle, UA hired private detectives to investigate the background of the women for information they could use to disqualify them as students. In the interim, Mrs. Foster accepted a teaching position in Mississippi.

Federal Judge H. Hobart Grooms heard the Myers and Lucy case and ruled in their favor. He used this case to set precedent for all other cases involving school integration. Judge Grooms ruled that the women were denied admission based on race and the color of their skin. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court which upheld the ruling of Judge Grooms. While the case was making its way through the courts, the University of Alabama left no stones unturned as they combed through the two women’s lives looking for any reason to not admit them. The investigators discovered that Mrs. Myers had a child out of wedlock. That was reason enough to disqualify her as a student based on moral grounds. It was wrongly believed that without Mrs. Myers that Dr. Foster would not pursue admission to the University.

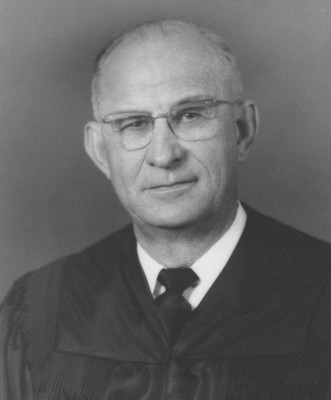

Harlan Hobart Grooms

(Nov. 7, 1900 – Aug. 23, 1991) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama.

On July 1, 1955, Judge Grooms entered an order in the case of Lucy v. Adams, permanently enjoining the Dean of Admissions of the University of Alabama from denying African-American students the right to enroll therein and pursue courses of study thereat solely on account of their race or color. (Wikipedia)

On February 1, 1956, Autherine Lucy became the first Black student to enroll at the University of Alabama. She was not assigned a dormitory room nor given permission to eat at any cafeteria. “Dr. Foster attended her first day of class on February 3rd, 1956 as a graduate student in library science, making her the first African American student admitted into a white public or private university in the state of Alabama.”

Autherine Lucy on campus at the University of Alabama, 1956 (Courtesy University of Alabama)

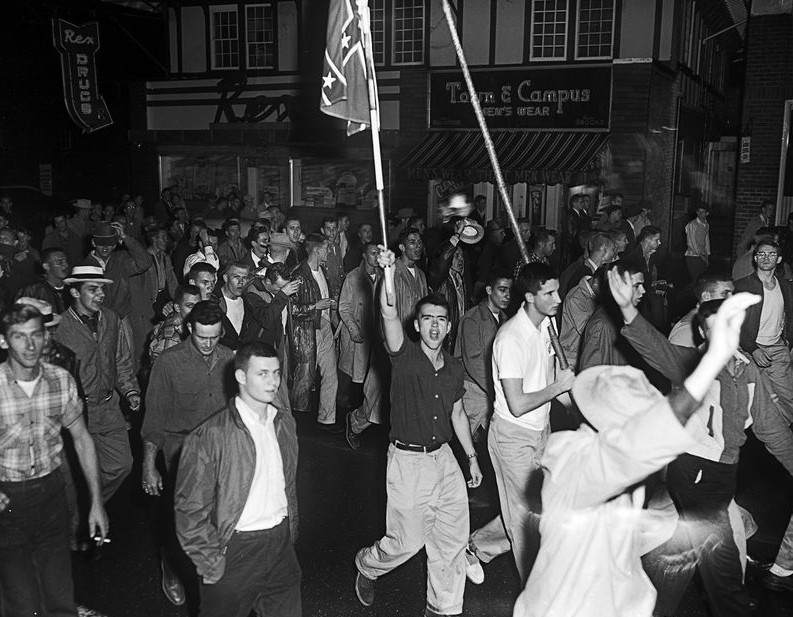

Protesters gather in Tuscaloosa to denounce Lucy’s admission to the University of Alabama.

Riots broke out at the University on February 6th, 1956, in protest of her admission. Some students put on “black face” to mock her. Others pelted her with rotten eggs and others shouted “kill her.” The students were joined by people who were not in any way connected to the University. Reports estimated the mob to be at least 2,000.

“It felt somewhat like you were not really a human being. But had it not been for some at the university, my life might not have been spared at all. I did expect to find isolation. I thought I could survive that. But I did not expect it to go as far as it did. There were students behind me saying, ‘Let’s kill her! Let’s kill her!’” (From a 1992 interview for the New York Times)

She found refuge in the Education Building that now bears her name. She was spirited away from the campus and later suspended, according to UA, for her safety. Her attorneys filed a complaint that accused the University of using the incidents on campus to get rid of her. The University, thinking that Dr. Foster was in compliance with the article, permanently expelled her. The expulsion was rescinded in 1988 and Dr. Foster returned to the campus with her daughter Grazia. They both graduated with masters degrees in Education in 1992.

Initially, it was difficult to obtain a teaching position in Texas because potential employers viewed her as a troublemaker because of her role in integrating the University of Alabama.

“Dr. Foster made a few speeches at NAACP events in Texas and Philadelphia, but such engagements waned as she fell out of the public eye. After living in Louisiana and Texas, the couple returned to Alabama in 1974, where Reverend Foster took a position as pastor of the New Zion Baptist Church in Bessemer, Jefferson County.”

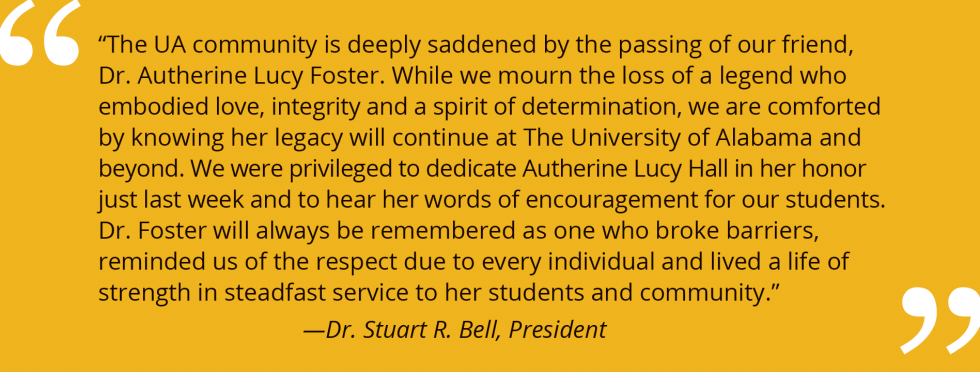

“The university has named an endowed scholarship in her honor and placed her portrait in the Ferguson Center on campus. On May 4, 2019, UA awarded Dr. Foster an honorary doctorate.” On February 25, 2022 UA dedicated Autherine Lucy Hall in honor of Dr. Autherine Juanita Lucy Foster. On March 3, 2022, Dr. Foster’s journey of reconciliation came to an end as she transitioned from time to eternity surrounded by her family at her home in Lipscomb, Alabama on March 3, 2022.”

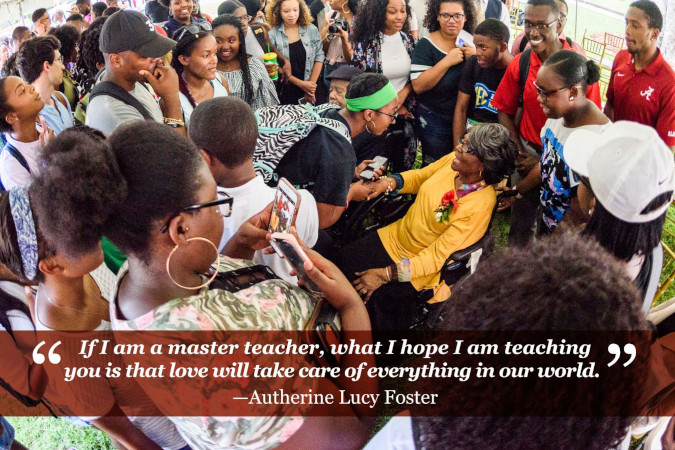

Dr. Autherine Juanita Lucy Foster was a selfless courageous trailblazer who opened the doors to higher education to countless students because she dared to take a path that had not been taken by others. She was courageous and spent her life serving others as an educator who inspired young people to follow rainbows, chase dreams, and to follow paths less taken to be all that God had called them to be.

She always had an open door and counted among her friends and acquaintances people from all walks of life who were encouraged by her constant smile, open hand, acts of bravery, and the lessons of reconciliation and joy that filled her life. Dr. Foster, literally, threw caution to the wind and sacrificed everything to give all people an opportunity to achieve dreams and lay-hold on the future.

Autherine Lucy Foster speaks at a ceremony at the University of Alabama in 2017.

The unveiling of a plaque in her honor at the University of Alabama in 2017.

Autherine Lucy Foster is center stage at the dedication ceremony for Autherine Lucy Hall at the University of Alabama, February 25 , 2022. She would pass away the following week.

TUSCALOOSA ROAD

by Eve Merriam (1916-1992)

Bright shone the sun as a wedding day,

Autherine Lucy was on her way.

The clay was fair, the sun bright shone,

Autherine Lucy was all alone.

Autherine Lucy was all alone:

Men like toads crept from under a stone,

Saw Autherine Lucy alone on her way;

Like rats clawing garbage from yesterday,

Reared back on their hind legs

and threw the first stone:

“Get Autherine Lucy — she’s all alone!”

No stone thrown however high

Can touch the sun up in the sky.

So tall rises freedom fully grown,

High as the sun in the sky ever shone.

So far shines freedom more and more known,

So fair rises freedom on her human throne,

Crowned by the world, no more alone.

A rain of curses stained the clay:

“Autherine Lucy — get away!”

A hail of hatred stoned the day:

“It’s Autherine Lucy — bar the way!”

No lie flung however wide

Can force the truth to step aside.

So freedom walks with a forward stride,

So Autherine Lucy, freedom’s bride

On your wedding day, the world by your side,

Hands outclassed to greet the bride.

Across the wide world, embracing pride.

Originally published in Montgomery Alabama, Money, Mississippi, and Other Places | Copyright © Eve Merriam, 1956, all rights reserved.

Resources

- Autherine Lucy Hall Dedication | The University of Alabama – YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pw-bc5jC21w&t=7s - Remembering Autherine Lucy Foster – University of Alabama News | The University of Alabama (ua.edu) https://news.ua.edu/2022/03/remembering-autherine-lucy-foster/

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 1954

https://www.nps.gov/articles/brown-v-board-of-education.htm1954: Brown v. Board of EducationOn May 17, 1954, in a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for students of different races to be unconstitutional. The decision dismantled the legal framework for racial segregation in public schools and Jim Crow laws, which limited the rights of African Americans, particularly in the South.Segregation in Schools

Elementary schools in Kansas had been segregated since 1879 by a state law allowing cities with populations of 15,000 or more to establish separate schools for black children and white children. African American parents in Kansas began filing court challenges as early as 1881. By 1950, 11 court challenges to segregated schools had reached the Kansas State Supreme Court. None of the cases successfully overturned the state law.NAACP Challenges Segregation in Court

In 1950, the Topeka Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) organized another case, this time a class action suit comprised of 13 families. The basis for the plaintiffs’ complaint was that their children were forced to walk or ride buses to reach segregated schools more than a mile away when there were white schools close to their houses. The Topeka NAACP filed suit on their behalf in February of 1951, but by August, the U.S. District Court ruled that, although segregation might be detrimental, it was not illegal. Citing the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the judges denied relief on the grounds that the black and white schools in Topeka were equal with respect to buildings, transportation, curricular, and educational qualifications of teachers.The plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1952 and were joined by four similar NAACP-sponsored cases from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. The court ruling combined these five cases under the heading Oliver L. Brown et. al. vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, (KS) et. al. Mr. Brown was the assigned lead plaintiff in the Kansas class action suit and became namesake of the court decision. Chief Council for the NAACP Thurgood Marshall argued before court that separate school systems for blacks and whites were inherently unequal, and thus violated the “equal protection clause” of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Marshall also argued that segregated school systems made black children feel inferior to white children, and thus such a system should not be legally permissible.

Separate, but Equal has ‘no place’

The Supreme Court Justices heard the case in the spring, but were unable to decide the issue by the end of the court’s term in June. The Justices decided to rehear the case in the fall with special attention paid to whether the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause prohibited the operation of separate public schools based on race. In September Chief Justice Fred Vinson, who had been a key stumbling block to a unanimous decision, died and was replaced by Governor Earl Warren of California. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican-American students in California school systems in 1947, after Mendez v. Westminster and when Brown v. Board of Education was reheard, Warren was able to bring the Justices to a unanimous decision. On May 14, 1954, Chief Justice Warren delivered the opinion of the Court, stating, “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.”The decision in Brown v. Board of Education forced the desegregation of public schools in 21 states and intensified resistance in the South, particularly among white supremacist groups and government officials sympathetic to the segregationist cause. In Virginia, U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. started the Massive Resistance movement, which sought to pass new state laws and policies as a means of keeping public schools from being desegregated. In one of the most notorious instances of resistance to the decision, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard in 1957 to keep black students from entering Little Rock Central High School.

For African Americans, the Supreme Court’s decision encouraged and empowered many who felt for the first time in more than half a century that they had a “friend” in the Court. The strategy of education, lobbying, and litigation that had defined the Civil Rights Movement up to that point broadened to include an emphasis on “direct action.” This included boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, marches, and other tactics that relied on mass mobilization, nonviolent resistance, and civil disobedience all of which would come to define the Modern Civil Rights Movement.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)[From Congressional Record, 84th Congress Second Session. Vol. 102, part 4 (March 12, 1956). Washington, D.C.: Governmental Printing Office, 1956. 4459-4460.]

THE SOUTHERN MANIFESTO:

The decision of the Supreme Court in the school cases Declaration of Constitutional principles

On March 12, 1956, Howard Smith of Virginia (above), chairman of the House Rules Committee, introduced the Southern Manifesto in a speech on the House floor. Formally titled the Declaration of Constitutional Principles, it was signed by 82 Representatives and 19 Senators—roughly one-fifth of the membership of Congress and all from states that had once composed the Confederacy. It marked a moment of southern defiance against the Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka (KS) decision, which determined that separate school facilities for black and white school children were inherently unequal.

Mr. [Walter F.] George. Mr. President, the increasing gravity of the situation following the decision of the Supreme Court in the so-called segregation cases, and the peculiar stress in sections of the country where this decision has created many difficulties, unknown and unappreciated, perhaps, by many people residing in other parts of the country, have led some Senators and some Members of the House of Representatives to prepare a statement of the position which they have felt and now feel to be imperative.

I now wish to present to the Senate a statement on behalf of 19 Senators, representing 11 States, and 77 House Members, representing a considerable number of States likewise. . . .

DECLARATION OF CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES

The unwarranted decision of the Supreme Court in the public school cases is now bearing the fruit always produced when men substitute naked power for established law.

The Founding Fathers gave us a Constitution of checks and balances because they realized the inescapable

lesson of history that no man or group of men can be safely entrusted with unlimited power. They framed this Constitution with its provisions for change by amendment in order to secure the fundamentals of government against the dangers of temporary popular passion or the personal predilections of public officeholders.

We regard the decisions of the Supreme Court in the school cases as a clear abuse of judicial power. It climaxes a trend in the Federal Judiciary undertaking to legislate, in derogation of the authority of Congress, and to encroach upon the reserved rights of the States and the people.

The original Constitution does not mention education. Neither does the 14th Amendment nor any other amendment. The debates preceding the submission of the 14th Amendment clearly show that there was no intent that it should affect the system of education maintained by the States.

The very Congress which proposed the amendment subsequently provided for segregated schools in the District of Columbia.

When the amendment was adopted in 1868, there were 37 States of the Union. . . .

Every one of the 26 States that had any substantial racial differences among its people, either approved the operation of segregated schools already in existence or subsequently established such schools by action of the same law-making body which considered the 14th Amendment.

As admitted by the Supreme Court in the public school case (Brown v. Board of Education), the doctrine of separate but equal schools “apparently originated in Roberts v. City of Boston (1849), upholding school segregation against attack as being violative of a State constitutional guarantee of equality.” This constitutional doctrine began in the North, not in the South, and it was followed not only in Massachusetts, but in Connecticut, New York, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania and other northern states until they, exercising their rights as states through the constitutional processes of local self-government, changed their school systems.

In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 the Supreme Court expressly declared that under the 14th Amendment no person was denied any of his rights if the States provided separate but equal facilities. This decision has been followed in many other cases. It is notable that the Supreme Court, speaking through Chief Justice Taft, a former President of the United States, unanimously declared in 1927 in Lum v. Rice that the “separate but equal” principle is “within the discretion of the State in regulating its public schools and does not conflict with the 14th Amendment.”

This interpretation, restated time and again, became a part of the life of the people of many of the States and confirmed their habits, traditions, and way of life. It is founded on elemental humanity and commonsense, for parents should not be deprived by Government of the right to direct the lives and education of their own children.

Though there has been no constitutional amendment or act of Congress changing this established legal principle almost a century old, the Supreme Court of the United States, with no legal basis for such action, undertook to exercise their naked judicial power and substituted their personal political and social ideas for the established law of the land.

This unwarranted exercise of power by the Court, contrary to the Constitution, is creating chaos and confusion in the States principally affected. It is destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through 90 years of patient effort by the good people of both races. It has planted hatred and suspicion where there has been heretofore friendship and understanding.

Without regard to the consent of the governed, outside mediators are threatening immediate and revolutionary changes in our public schools systems. If done, this is certain to destroy the system of public education in some of the States.

With the gravest concern for the explosive and dangerous condition created by this decision and inflamed by outside meddlers: We reaffirm our reliance on the Constitution as the fundamental law of the land.

We decry the Supreme Court’s encroachment on the rights reserved to the States and to the people, contrary to established law, and to the Constitution.

We commend the motives of those States which have declared the intention to resist forced integration by any lawful means.

We appeal to the States and people who are not directly affected by these decisions to consider the constitutional principles involved against the time when they too, on issues vital to them may be the victims of judicial encroachment.

Even though we constitute a minority in the present Congress, we have full faith that a majority of the American people believe in the dual system of government which has enabled us to achieve our greatness and will in time demand that the reserved rights of the States and of the people be made secure against judicial usurpation.

We pledge ourselves to use all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this decision which is contrary to the Constitution and to prevent the use of force in its implementation.

In this trying period, as we all seek to right this wrong, we appeal to our people not to be provoked by the agitators and troublemakers invading our States and to scrupulously refrain from disorder and lawless acts.

Signed by:

Members of the United States Senate

Walter F. George, Richard B. Russell, John Stennis, Sam J. Ervin, Jr., Strom Thurmond, Harry F. Byrd, A. Willis Robertson, John L. McClellan, Allen J. Ellender, Russell B. Long, Lister Hill, James O. Eastland, W. Kerr Scott, John Sparkman, Olin D. Johnston, Price Daniel, J.W. Fulbright, George A. Smathers, Spessard L. Holland.

Members of the United States House of Representatives

Alabama: Frank W. Boykin, George M. Grant, George W. Andrews, Kenneth A. Roberts, Albert Rains, Armistead I. Selden, Jr., Carl Elliott, Robert E. Jones, George Huddleston, Jr.

Arkansas: E.C. Gathings, Wilbur D. Mills, James W. Trimble, Oren Harris, Brooks Hays, W.F. Norrell.

Florida: Charles E. Bennett, Robert L.F. Sikes, A.S. Herlong, Jr., Paul G. Rogers, James A. Haley, D.R. Matthews.

Georgia: Prince H. Preston, John L. Pilcher, E.L. Forrester, John James Flynt, Jr., James C. Davis, Carl Vinson, Henderson Lanham, Iris F. Blitch, Phil M. Landrum, Paul Brown.

Louisiana: F. Edward Hebert, Hale Boggs, Edwin E. Willis, Overton Brooks, Otto E. Passman, James H. Morrison, T. Ashton Thompson, George S. Long.

Mississippi: Thomas G. Abernathy, Jamie L. Whitten, Frank E. Smith, John Bell Williams, Arthur Winstead, William M. Colmer.

North Carolina: Herbert C. Bonner, L.H. Fountain, Graham A. Barden, Carl T. Durham, F. Ertel Carlyle, Hugh Q. Alexander, Woodrow W. Jones, George A. Shuford.

South Carolina: L. Mendel Rivers, John J. Riley, W.J. Bryan Dorn, Robert T. Ashmore, James P. Richards, John L. McMillan.

Tennessee: James B. Frazier, Jr., Tom Murray, Jere Cooper, Clifford Davis.

Excerpts from the Southern Manifesto on School Integration

[From Congressional Record, 84th Congress Second Session. Vol. 102, part 4 (March 12, 1956).

Washington, D.C.: Governmental Printing Office, 1956. 4459-4460.]