By Dr. Wayne Flynt

In my not-so-humble opinion, the state of Alabama has produced an unparalleled number of distinguished African Americans.

In my not-so-humble opinion, the state of Alabama has produced an unparalleled number of distinguished African Americans.

Someone will have to prove to me that any other state matches the accomplishments below, much less exceeds them.

Measure culture anyway you please—popular or elite; folkish or institutional; art; music, literature; education; leaders of the modern Civil Rights Movement; sport — and Alabama’s heritage sustains my argument.

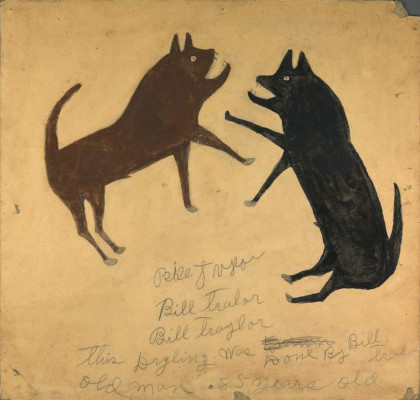

Let’s Begin With Art

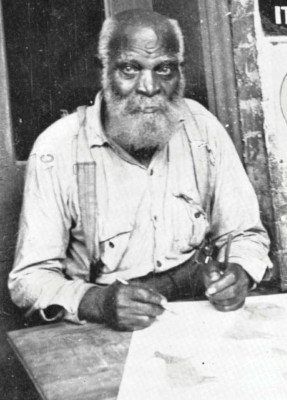

Appropriately enough in the year of Alabama’s bicentennial, the Smithsonian Museum in the Nation’s capital launched a one-man exhibition of the folk art of Bill Traylor, a man born in slavery in 1853, who, by his death 96 years later, was one of America’s most renowned and prolific self-taught artists (though he had to share honors with a host of others, including Thornton Dial, Mose T., Jimmie Lee Sudduth, Charlie Lucas, and Lonnie West).

Music

African American musicians from the “Heart of Dixie” provided Auburn University English professor Newman I. White nearly half the songs he included in his classic book, American Negro Folk Songs.

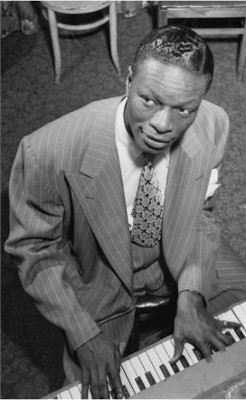

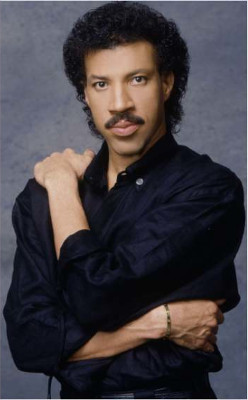

Florence native W. C. Handy bequeathed America the Blues. Mobile’s James Reese Europe contributed syncopated jazz in the form of the Fox Trot, which he introduced to America, then carried to France and England as conductor of the 15th Colored Army Band during the First World War. The dance dominated Jazz Age culture on two continents during the Roaring Twenties. The Erskine Hawkins band of Birmingham and Alabama State University provided swing dancers the iconic Tuxedo Junction a generation later. And the band’s piano player, Avery Parish, wrote After Hours, often referred to in the 1940s and 1950s as the “Negro National Anthem.” Montgomery’s Nat “King” Cole and Tuskegee’s Lionel Ritchie were among the most popular “crossover” (their popularity among Black audiences was matched by their celebrity among Whites) vocalists for two successive generations of Americans.

Literature

Alabama-connected authors could claim dominance of 20th century African American writing. Although some Americans refer to the “Harlem Renaissance” as if the great writers of the era all came from New York City, the majority came from the South, including the remarkable Zora Neale Hurston, who was born in Notasulga, Alabama, and is often referred to as the movement’s co-founder (along with her friend, Langston Hughes). Hurston’s novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, is also considered by many scholars and readers to be the nation’s finest early feminist fiction.

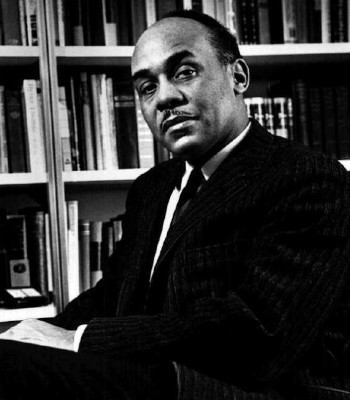

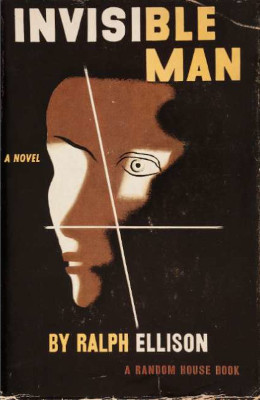

Ralph Ellison travelled to New York after completing his college work at Tuskegee University where he used characters and experiences there as the basis for Invisible Man, which many scholars consider the greatest novel ever written about the Negro experience in America.

Ellison’s classmate at Tuskegee, Albert Murray of Mobile, followed his friend to New York City where he became the unparalleled literary interpreter of jazz.

Birmingham-born Margaret Alexander Walker wrote the novel Jubilee, which is often referred to as the African American equivalent to Gone With The Wind.

Education

Perry County’s Lincoln Memorial School graduated the wives of three major leaders of the Civil Rights Movement—Coretta Scott King (Mrs. Martin Luther King); Juanita Abernathy (Mrs. Ralph David Abernathy) and Jean Childs Young (Mrs. Andrew Young). The Childs family became one of the nation’s most elite and successful African American families in the 20th century, sending their children to Ivy League universities and thence on to distinguished careers in law, medicine, and higher education.

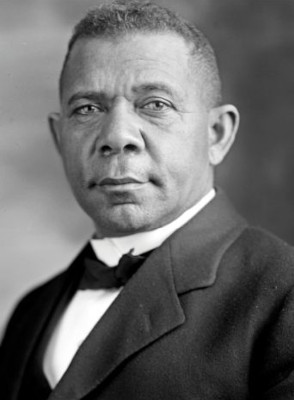

Tuskegee Institute not only represented the zenith of applied, practical Negro education for decades, but also furnished two of its most influential and respected leaders, President Booker T. Washington, and agronomist George Washington Carver.

By producing seven of the most important leaders of the modern Civil Rights Movement—educator Jo Ann Robinson, seamstress Rosa Parks, Baptist ministers Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth, attorneys Fred Gray and Arthur Shores and labor unionist E.D. Nixon—Alabama could lay claim to being the incubator of the nation’s most important social and political revolution since its rebellion against Great Britain. Among other accomplishments they founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Montgomery’s Women’s Political Council, the Montgomery Improvement Association/Bus Boycott, and Birmingham’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights. Arguably the state was ground zero for the three major encounters during the nation’s longest struggle for equal rights in Selma, Montgomery, and Birmingham.

Sports

Finally, for a state long obsessed with sport African Americans bequeathed Alabama its greatest athletes, did more to bring about racial integration and justice than any other cohort of the population, and left the largest imprint on sport in America.

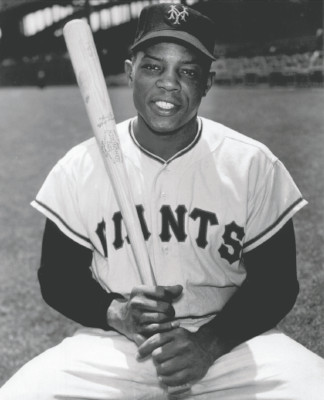

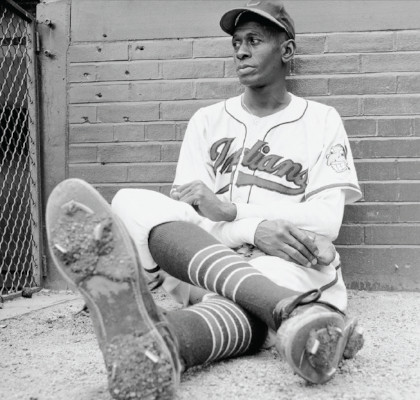

When the Birmingham News selected the 10 greatest Alabama athletes of the 20th century, baseball players Willie Mays ranked third, Henry “Hank” Aaron fourth, and Leroy “Satchel” Paige 10th. Nationally, Sporting News selected Mays the second best baseball player of the century and Aaron the home run champion. Of the top 11 home run hitters, Aaron and Mays ranked first and third, Willie McCovey of Mobile, 11th. Aaron and Mays tied for most appearances in All Star games.

Paige, a casualty of early 20th century apartheid, played mainly in the Negro League where he pitched an astounding 2,500 games, won 2,000, threw 250 shutouts, and 100 no-hitters during perhaps the longest career in professional baseball history. Renowned major leaguer Joe DiMaggio called Paige the best pitcher he ever faced.

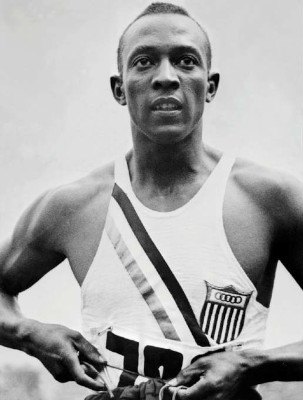

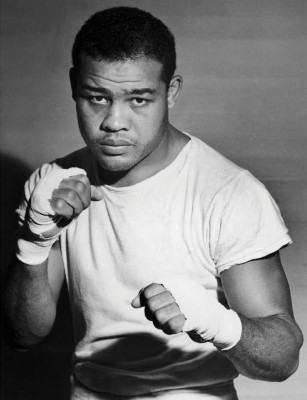

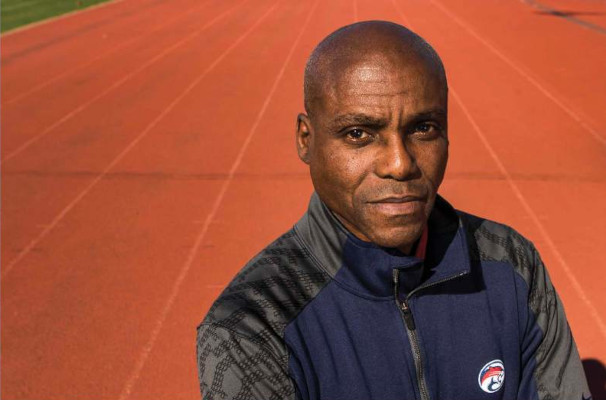

When the sports network ESPN selected the top 10 American athletes of the century, track star Jesse Owens from Lawrence County and Willie Mays constituted one-fifth of the list. Birmingham-born sprinter Carl Lewis made other lists, while world boxing heavyweight champion Joe Louis of Lafayette, along with Jesse Owens, made the Associated Press top 10 list. One British publication listed three Alabamians, all Negroes, among its list of millennium record breakers; Joe Louis, Jesse Owens, and Hank Aaron.

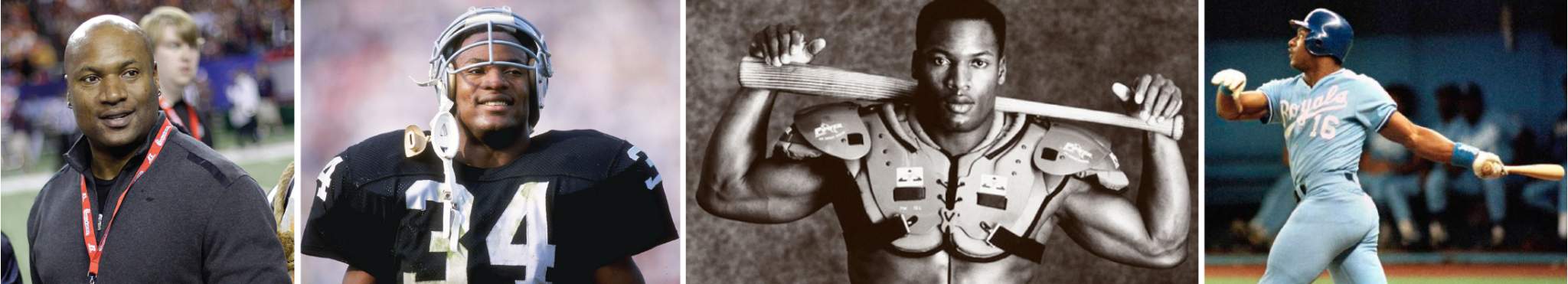

Vincent “Bo” Jackson of Birmingham—who won the Heisman Trophy, emblematic of the nation’s best football player, the Walter Camp Award, and Sporting News Player of the Year, all in 1985—is considered by many sports historians to be the greatest college player ever. He also became one of a handful of athletes to star in two professional sports. As a running back for the Oakland Raiders, he played in the 1990 Pro Bowl. As a baseball star for the Kansas City Royals, he played in the 1989 All Star game. He also starred as a sprinter, hurdler, jumper, thrower, and decathlete for Auburn University’s track and field teams. Many considered him not only the greatest college football player ever but also the most gifted multi-sport athlete of all time. Of the five Heisman winners from Auburn and the University of Alabama, six (Bo Jackson and Cam Newton at Auburn; Mark Ingram, Derrick Henry, DeVonta Smith and Bryce Young at Alabama) were African Americans.

When Juanita Abernathy spoke at the 45th anniversary of the Montgomery Bus Boycott at Alabama State University in February, 2001, she mused that her home state had produced a “great people.” She did not mean her own family or even the entire population of the state, many of whom had lynched her people and done everything within their power to establish and preserve the American apartheid. She meant her race, its distinctive way of life, historical tragedies, and long persecution. She meant the way in which hard times had produced endurance, patience, courage, faith in God, and hope for the future. “A great people” was her shorthand for proud African Americans from Alabama.

Dr. Wayne Flynt, Professor Emeritus in the Department of History at Auburn University, is the author of 11 books, and one of the most recognized and honored scholars of Southern history, politics and religion. His memoir, Keeping the Faith: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Lives, is about his experiences in the Civil Rights movement. The September 15, 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church was key in shaping Flynt’s views on the movement, confirming for him that those against civil rights were wrong and those who supported the movement were right. Flynt notes that being 70 allowed him some freedom in writing. “I’m retired, I don’t give a hoot what anybody thinks about me …nobody can get me fired because you can’t fire someone from retirement.”