Political activist, writer, and public speaker Angela Davis has never wavered in her quest for women’s rights and the eradication of poverty and oppression. The energetic Davis became embroiled in controversy in California at the end of the 1960s and emerged as an international symbol of a proud, defiant African American woman under political siege. Davis was fired from a prestigious professorship because she was a Communist and later was jailed for sixteen months for crimes she did not commit. For a time in the early 1970s she was on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s “Ten Most Wanted List,” a distinction that brought her worldwide recognition as a victim of political repression. As Melba Beals put it in People, “In the idol-seeking rebellion of the American ’60s, Angela Davis became a lightning rod almost in spite of herself.” Subsequent decades have found Davis to be an impassioned worker for the causes of nationalized health care, civil rights, and nuclear disarmament.

“Angela is one of the most well-known women in the United States—and one of the busiest,” wrote Cheryll Y. Greene in Essence magazine.”She is active in five organizations, among them the Communist Party [of the] U.S.A., in which she is the major Black figure and plays a leading role… She travels extensively both in the United States and abroad, lecturing to diverse audiences, from college students to white male union members. In 1980 and 1984 she ran for vice president of the United States on the Communist Party ticket.”

Davis admitted in Essence that she is “always amazed” that she is invited to give so many speeches even now, decades after young people demonstrated on her behalf with “Free Angela” placards. “I know I wouldn’t have sought this kind of public life—if it had been something that I could have chosen,” she said. “I didn’t choose to be where I am now. I didn’t choose to be the target of the repression at that time. It just happened that way. It was, in a sense, a historical accident that I was the one. But I feel that I should accept that role for what it can accomplish for all of us.”She added: “I try never to take myself for granted as somebody who should be out there speaking. Rather, I’m doing it only because I feel there’s something important that needs to be conveyed.”

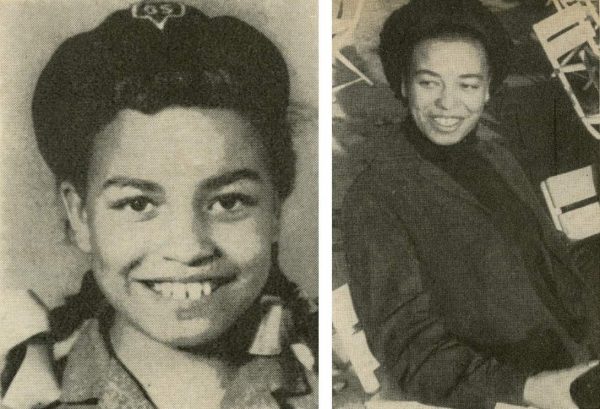

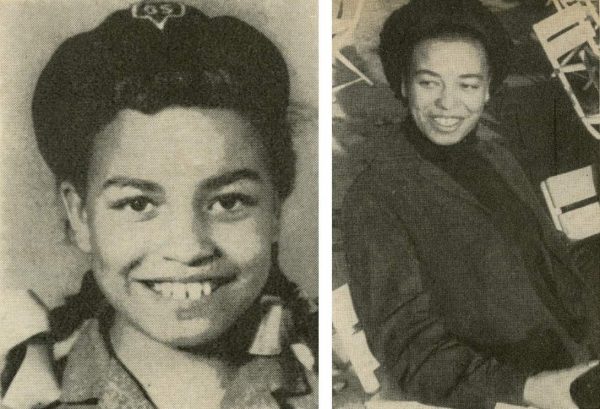

Far left: Davis as a 10-year-old Girl Scout in Birmingham, Alabama, the place from which, she says, “my political involvement stems”

Left: As a student at the Institute of Social Research at Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany. Davis studied the work of philosophers Kant, Hegel, and Adorno. (Wikipedia)

Left: Davis as a 10-year-old Girl Scout in Birmingham, Alabama, the place from which, she says, “my political involvement stems”

Right: As a student at the Institute of Social Research at Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany. Davis studied the work of philosophers Kant, Hegel, and Adorno. (Wikipedia)

Angela Davis was born in 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama, one of four children of B. Frank and Sallye E. Davis. Her parents were both schoolteachers, but her father left the profession and bought his own gas station. The family lived in a segregated neighborhood, and Davis attended segregated public schools. As a youngster she had ample opportunity to observe the effects of racism on the lives of her neighbors and friends.

While she was still a young girl, Davis began to attend civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham with her mother. The white majority responded to the demonstrations with clandestine hostility. So many homes in Davis’s neighborhood were bombed by marauding white supremacists that the area became known as “Dynamite Hill.” Attempts by Davis and some of her friends to conduct interracial study groups were disbanded by police. The racially motivated violence and the unfair laws governing blacks’ behavior in public places helped to instill in Davis a sense of social purpose, as well as a deep resentment of the white power structure.

Davis’s mother spent summers working toward a master’s degree at New York University. Often Davis spent the summers in Manhattan too, and after her sophomore year of high school in Birmingham she earned a scholarship to attend Elizabeth Irwin High, a private school in Greenwich Village. A straight-A student at home in Birmingham, Davis had to struggle to achieve the same grades in New York. She added summer courses to her schedule and repeated some of her hardest classes. In 1961 she graduated and accepted a scholarship to Brandeis University.

Activism Fueled By Education

At Brandeis, Davis majored in French literature. She spent one school year abroad studying at the Sorbonne. There she met students from Algeria and other African nations who had grown up under colonial rule. Their stories of discriminatory conditions in their homelands deepened her commitment to radical social change. She was further inflamed when news reached her of a bombing of a Birmingham church (16th Street Baptist Church) that killed four children she had known. Davis returned to Brandeis in search of some political philosophy that could mandate changes in the treatment of blacks—not only in America, but on the international level.

Her search brought her to the classroom of Herbert Marcuse, a Marxist professor of philosophy. Marcuse directed Davis to the tenets of socialism and communism. In her autobiography, Angela Davis, the activist wrote: “The Communist Manifesto [by nineteenth-century German philosopher and political economist Karl Marx] hit me like a bolt of lightning. I read it avidly, finding in it answers to many of the seemingly unanswerable dilemmas which had plagued me …. I began to see the problems of Black people within the context of a large working-class movement …. What struck me so emphatically was the idea that once the emancipation of the proletariat

became a reality, the foundation was laid for the emancipation of all

oppressed groups in society.”

Davis graduated from Brandeis with top honors in 1965 and attended graduate school at the University of Frankfurt in Germany. She continued her studies of philosophy there, mastering the German language as well as the theories of knowledge set forth by German philosophers Immanuel Kant and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Although her professors were impressed with her scholarship, they could not persuade her to stay in Germany as the social situation deteriorated in America. In 1967 Davis returned to the United States to finish work on her master’s degree at the University of California, San Diego.

“Free Angela”

In California Davis finished her master’s degree and began work toward her doctorate. She also joined a number of activist groups, including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panthers. Her most important affiliation came in June of 1968, when she formally joined the Communist Party and became involved with the Che-Lumumba Club, an all-black Communist collective in Los Angeles. As a member of Che-Lumumba, she helped to organize militant demonstrations and protests designed to focus public attention on the plight of minorities. And thus her troubles began.

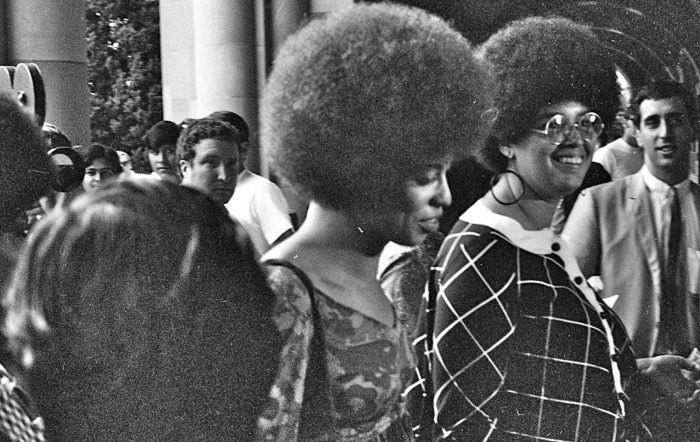

Davis (center, without glasses) enters Royce Hall with Kendra Alexander at UCLA for her first lecture, October 1969.

The University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) had hired Davis as an assistant professor of philosophy in 1969. She taught four courses: “Dialectical Materialism,” “Kant,” “Existentialism,” and “Recurring Philosophical Themes in Black Literature.” Quickly she became a popular teacher on the UCLA campus, but an ex-FBI informer leaked the news that Davis was a member of the Communist party. The information made the newspapers, and UCLA’s board of regents—which included then-governor Ronald Reagan—dismissed her from her post. The situation bore an uncanny resemblance to the deplorable “Red Scare” in the 1950s. Fellow faculty members and even the university president overwhelmingly condemned the regents’ action as illegal and an infringement on academic freedom. Davis was reinstated by court order, but when her contract expired the following year she was dismissed again.

By that time Davis had become actively involved in the cause of the Soledad Brothers, a group of inmates at California’s Soledad Prison who were treated especially harshly because they had tried to organize a Marxist group among the prisoners. Davis led demonstrations and gave speeches calling for parole of the young black prisoners. When one of the prisoners was shot by a guard in an incident ruled “justifiable homicide” by the warden, Davis grew even more strident in her demands. Her public exhortations drew anonymous threats by telephone and by mail, so she purchased several weapons and stored them in the headquarters of the Che-Lumumba Club.

On August 7, 1970, a teen-aged sibling of one of the Soledad Brothers used the firearms Davis had purchased to stage a dramatic prisoner rescue and hostage-taking attempt at California’s Marin County Courthouse. The attempt was foiled in a barrage of gunfire that killed a county judge. Quickly the firearms were traced to Davis, and she fled into hiding. The FBI responded by placing her on the “Ten Most Wanted List” and undertaking a massive search for her. Two months later they found her in New York City and extradited her to California, where she was held in prison for over a year.

Once a tireless crusader for the incarcerated, Davis soon found herself

behind bars, a victim and—in many minds—a political prisoner. “That period was pivotal for me in many respects,” Davis told Essence. “I came to understand much more concretely many of the realities of the Black struggle of that period.” Davis’s case became an international issue, especially in the Soviet Union, and demonstrations on her behalf were held on both sides of the Atlantic. “Free Angela” picket signs and lapel pins became a catchword for the mistreatment of blacks by an overzealous federal law enforcement system.

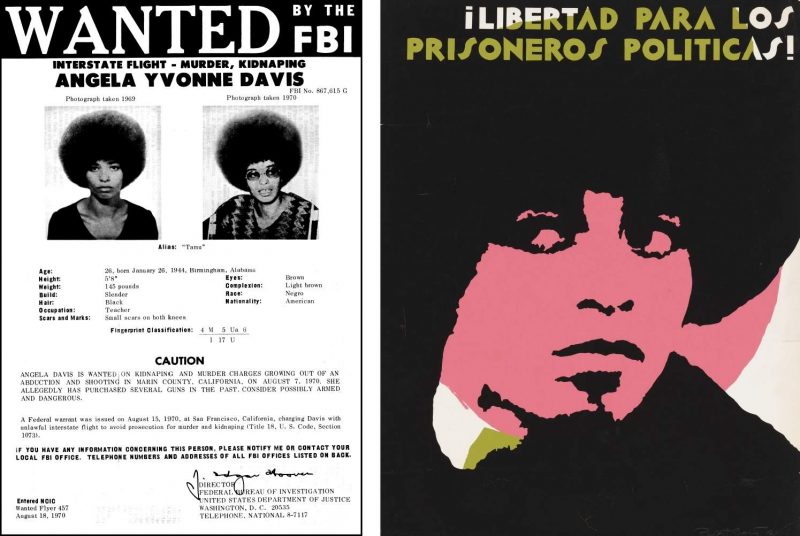

Near right: Davis was wanted by the FBI on a federal warrant issued August 15, 1970, for kidnapping and murder.

On August 18, 1970, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover listed Angela Davis on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List.

Near left: Poster by Rupert García featuring an illustration of Angela Davis, 1971.

The poster reads:

¡LIBERTAD PARA LOS PRISONEROS POLITICAS! which translates to “Freedom for political prisoners!”.

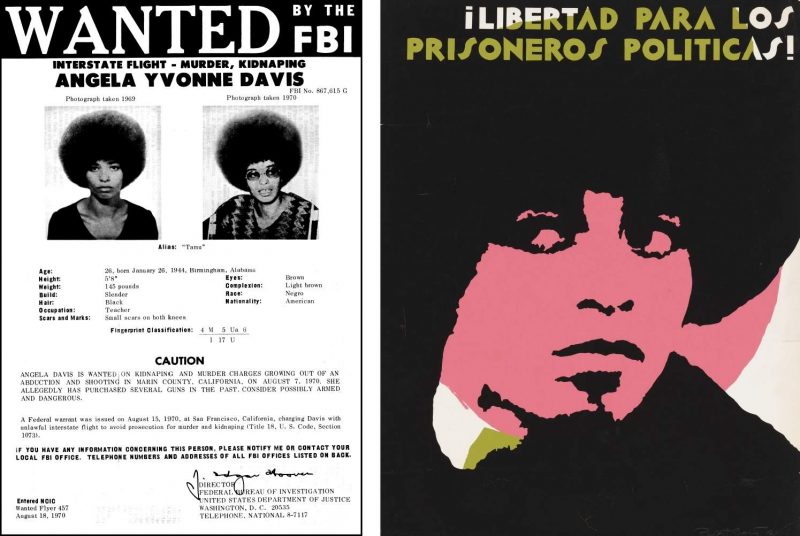

Left: Davis was wanted by the FBI on a federal warrant issued August 15, 1970, for kidnapping and murder.

On August 18, 1970, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover listed Angela Davis on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List.

Right: Poster by Rupert García featuring an illustration of Angela Davis, 1971.

The poster reads: ¡LIBERTAD PARA LOS PRISONEROS POLITICAS! which translates to “Freedom for political prisoners!”.

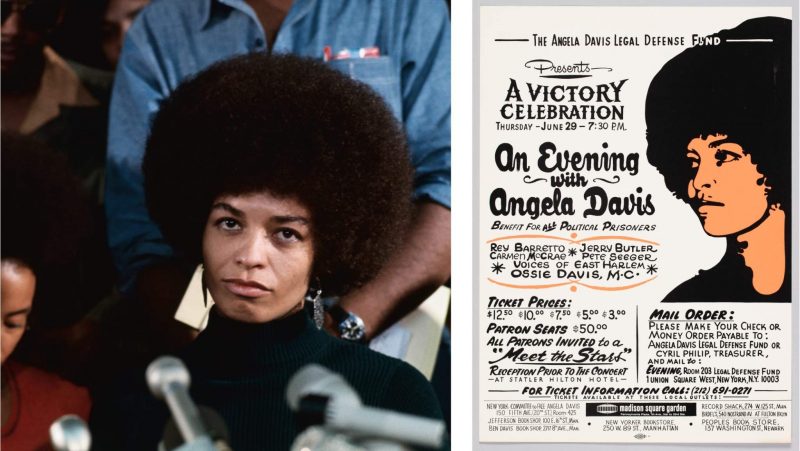

Davis was taken to trial on charges of kidnapping, conspiracy, and murder in the spring of 1972. Her defense was able to prove that she did not help to plan or execute the incident at the Marin County Courthouse, and a jury of eleven whites and one Mexican American acquitted her of all charges. Finally free, Davis embarked on a national lecture tour and visited the Soviet Union, where she was accorded a hero’s welcome. As the 1970s progressed, she became a well-known lecturer and writer who demanded a total reassessment of attitudes about the black family, an overhaul of repressive prison systems, and a black-white coalition for the formation of a socialized state.

The Communist Party of the United States has benefitted from Davis’s

talents for decades. Her presence in the party helped to change the African American perception of communism and bolster black membership. In 1980 and again in 1984 the party nominated her as its vice-presidential candidate. Progressive magazine contributor Julius Lester has commented that, with Davis, “one is left with the impression of a woman who lives as she thinks it necessary to live and not as she would like to, if she allowed herself to have desires. She seems to be a woman of enormous self-discipline and control, who willed herself to a total political identity. Her will is so strong that, at times, it is frightening.”

Addresses Issues Of Race, Gender, And Culture

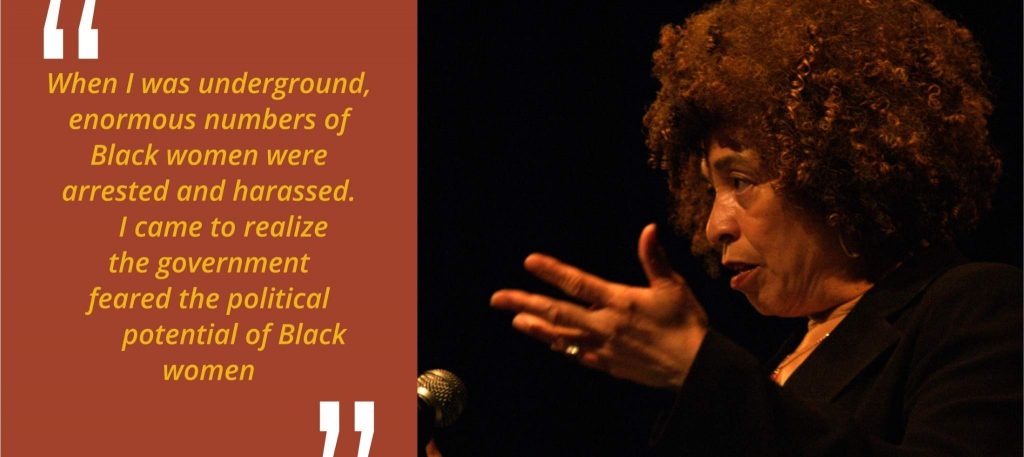

The years have not dimmed Davis’s ardor for her causes, nor have they softened her philosophy. As a teacher at such colleges as San Francisco State University and the University of California at Santa Cruz, she has developed courses on women’s issues from a global perspective. Her ideas on the subject are presented in two collections of essays, Women, Race & Class and Women, Culture & Politics. Davis told Essence: “Something happened during the period of my persecution by the government and the FBI and others. When I was underground, enormous numbers of Black women were arrested and harassed. I came to realize the government feared the political potential of Black women—and that that was a manifestation of a larger plan to push us away from political involvement.”

Davis said that knowledge helped to empower her and other black women as well. “A new collective consciousness was emerging. I think that during that very compressed historical moment we managed to formulate many of the issues that were of concern to us. And to formulate responses to the propagandistic assault, which are still valid 20 years later. That is what is so fascinating to me, to recognize that 20 years have gone by, yet many of the ideas raised during that period have not become historically obsolete.”

A self-avowed “soldier of freedom,” Davis is encouraged by a strain of militancy she sees in young Americans. She calls for multicultural coalitions and global strategies to achieve equality for all peoples. “It is no longer possible for various groups to live and function and struggle in isolation,” she told Ebony. “While we may specifically be involved in our own particular struggles, our vision has to be that we understand how our own issues relate to the issues of others. My consciousness has grown so that when I speak and write, I make a point of discussing the need for understanding how Native Americans, Latinos, and other people of color are marginalized in this society.”

As the 1990s progressed, Angela Davis remained on the front line, fighting for women’s rights, for a global peace plan including nuclear disarmament, for enhanced opportunities for workers, and especially for affordable health care for all American women. “Black women have no choice but to force the government to take responsibility for all its citizens,” she told Essence. “The budget cutting of the Reagan administration that abolished many programs vital to the poor must be restored. Ultimately, the economic system will have to be changed. I don’t think that under this system we will ever achieve economic power or equality. Some Black people, yes. But the majority still suffer now more than ever before.”

Also in Essence, Davis concluded on behalf of women of color everywhere: “It’s about time, the decade of the nineties—as we prepare for a new century—to claim our voice and to demand that our community give us the respect that we have given it for as many decades and centuries as we have been present on this continent.”

U2 concert, Soldier Field, Chicago, 2011

RESOURCES

SELECTED WRITINGS

- (With others) If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance, Third Press, 1971, reprinted, Okpaku Communications, 1992.

- Angela Davis: An Autobiography, Random House, 1974, reprinted,

International Publications, 1988. - Women, Race & Class, Random House, 1983.

BOOKS

- Ashman, Charles R., The People vs. Angela Davis, Pinnacle Books, 1972.

- Smith, Nelda J., From Where I Sat, Vantage, 1973.

LINKS

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angela_Davis

- https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/mar/05/angela-davis- on-the-power-of-protest-we-cant-do-anything-without-optimism

- https://www.thehistorymakers.org/biography/angela-davis-40

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lwRIJsLBD60

- https://www.goodreads.com/author/list/5863103.Angela_Y_Davis