Beyond the Book Honorees

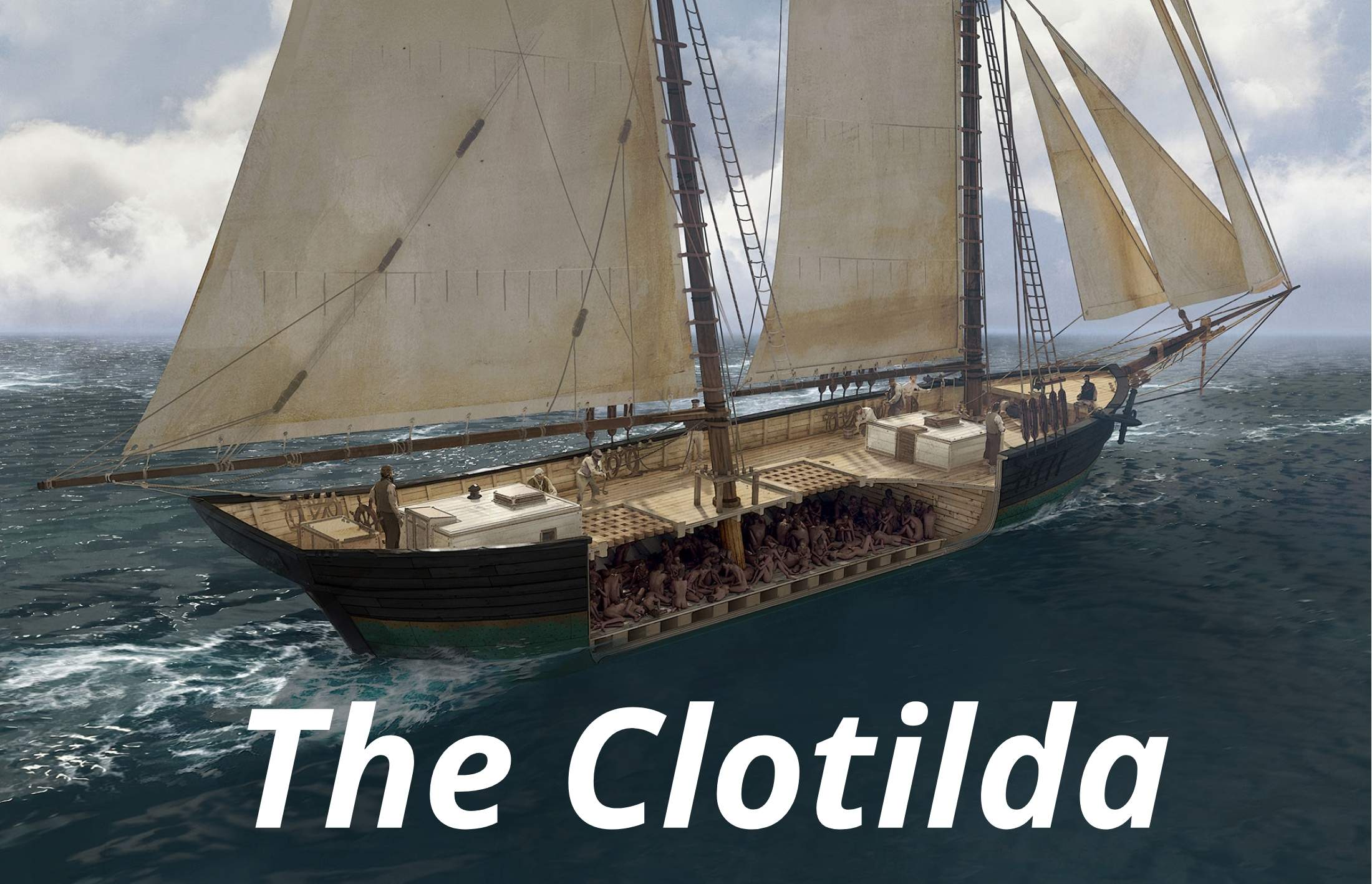

The schooner Clotilda smuggled African captives into the U.S in 1860.

It was burned and sunk in an Alabama river after bringing

110 imprisoned people across the Atlantic,

more than 50 years after importing slaves

was outlawed.

After extensive review and study, the Alabama Historical Commission announced

on May 22, 2019, that wreckage discovered in a remote arm of the Mobile River

was indeed the schooner Clotilda, the last known United States slave ship

to bring enslaved people from Africa to the United States.

The story below gives a first-hand account of the

unbearable life of slaves onboard the Clotilda.

‘Where are we?’

By Darron Patterson

We had walked and walked until my legs couldn’t walk anymore. That’s when the angry woman with the shrunken head tied to her waist hit me from behind and screamed ‘Go on!’ I struggled to get up, then saw my friend Osia fall. But they beat him until he got up, too. None of us knew what was happening or why. All we knew is we wanted to go home.

In the distance we saw this big boat far away out in the water, and on the shore we saw these men with guns standing next to a smaller boat. They yelled “Get in!” to a few of us … about 15 or 20 … and then they started paddling us out toward the big boat.

When we got there, they made us take off all our clothes before we got on board. We didn’t have much on anyway, but they made everyone … even the girls … get naked. When we got on board they made us climb down wooden steps into a dark room that smelled of rotten meat, and we were chained to walls and posts. Soon, more of my friends came and were chained.

Then, more and more and many more came … all naked and getting chained to walls and posts.

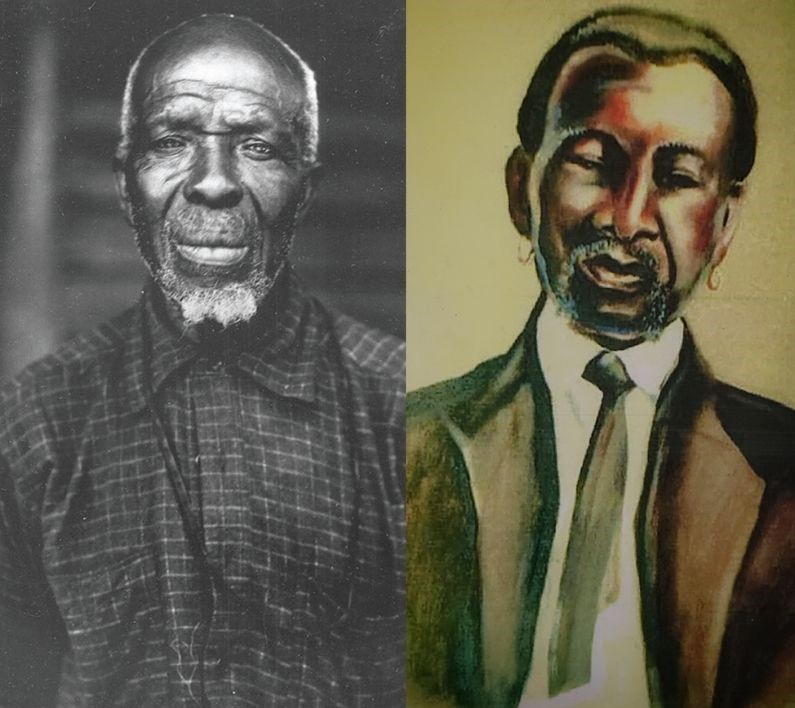

Before long there was no room to move, and it suddenly went dark as they closed the top to the room. My friend Cudjo was chained right across from me and he said: ‘Are you alright Kupollee?’ I slowly nodded yes, but it was a lie. I was not alright.

It wasn’t long after that the ship began to move … shaking back and forth, up and down, and tossing us into each other. Girls were crying. Some got sick and threw up on each other. But we had no water to wash them. No water to clean ourselves from the messes when made after relieving ourselves.

The men with guns on deck would throw bread and raw meat down to us through the holes in the door to the room. The holes let us breathe.

This went on for around 7 days. We know because we counted the sunrises. We knew to get back home we would have to know how many sunrises it would take.

-continue scrolling-

Left to right: Cudjo Lewis, one of the last survivors of the Clotilda, died in 1935 at the age of 94.

Image: Erik Overbey Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama

Portrait of Pollee Allen (whose African name was Kupollee), one of the survivors of the Clotilda voyage from the Kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa to Alabama. Image provided by the family.

Over 100 African captives survived the brutal, six-week passage from West Africa to Alabama in Clotilda’s cramped hold. Originally built to transport cargo, not people, the schooner was unique in design and dimensions—a fact that helped archaeologists identify the wreck.

Jason Treat and Kelsey Nowakowski for National Geographic.

Clotilda rendering: Thom Tenery

They would take us back to the room, and bring more up. This went on for a long time, but not every one of us came back to the room. Some of the girls didn’t come back. And then we would hear screams. We knew it was the girls. They’d scream and whimper. We knew it was the girls. We knew the men with the long guns were hurting them, and we were sad.

After extensive review and study, the Alabama Historical Commission announced on May 22, 2019, that the wreckage discovered in a remote arm of the Mobile River was indeed the schooner Clotilda, the last known American slave ship to bring enslaved people from Africa to the United States.

Left: Historian Ben Raines with wreckage from the slave ship Clotilda

Photo: Guy Busby/Alabama Public Radio

After more days dragged on, we stopped counting the sunrises. We stopped crying as we sat in the room that by now had a smell so horrible I cannot describe it. And the cries of the girls on deck stopped, too. Girls who had been brought back to the room told others what the men had done to them.

And as they were led up the ladder by the men with guns, they looked back at everyone as if to say:

‘I am strong. I will be back. Do not be sad.’

The days staggered by. But the ‘exercise sessions’ seemed to come quicker and quicker. The girls those men had taken on deck no longer cried. The smell of our ‘dungeon’ room was something we’d become accustomed to. It was as if we’d just settled in and waited to learn our fate.

Then one day, the boat stopped. We had no idea how many days had gone by, but we heard men with voices we hadn’t heard before.

Where are we? Will anybody ever know what happened to us?

How will our story end?

Darron Patterson is the President of the Clotilda Descendants Association and the great, great grandson of Kupollee (Allen)

Resources

Clotilda Descendants Association – THE STORY OF THE CLOTILDA 110

Finding the last ship known to have brought enslaved Africans to America and the descendants of its survivors

November 29, 2020 interview on 60 Minutes by Anderson Cooper

Last American slave ship is discovered in Alabama – National Geographic magazine

The ‘Clotilda,’ the Last Known Slave Ship to Arrive in the U.S., Is Found – The Smithsonian magazine

‘Remarkable’ woman discovered as last known survivor of transatlantic slave trade

CNN

THE CLOTILDA

The Last American Slave Ship