Saint Bartley Primitive Baptist Church. WSFA

SAINT BARTLEY PRIMITIVE BAPTIST CHURCH, HUNTSVILLE

Alabama became a state in 1819, and just one year later in 1820, Saint Bartley Primitive Baptist Church was organized by Elder William Harris while blacks were still enslaved. It is recognized as the oldest black church in Alabama.

Originally known as “Huntsville African Baptist Church,” Saint Bartley was first located in the Old Georgia Graveyard, which was considered a focal point for the black community. Since an Alabama law prohibited slaves from gathering unless a White man was present, they often held services at night, singing spirituals and hymns while hearing sermons of hope.

The church that had been located in the Old Georgia Graveyard was destroyed when the Union soldiers occupied Huntsville. After the Civil War, President Ulysses Grant appropriated money so that it could be rebuilt. In 1872, a new church was rebuilt and rededicated at a location near its original home. That’s when the name was changed from “Huntsville African Baptist Church” to “Saint Bartley Primitive Baptist Church.” According to an article published in The Huntsville Times, the church’s name derived from one of its early elders—Bartley Harris—who was instrumental in the church’s growth and progress.

Saint Bartley played an integral role in the national organization of black Primitive Baptist churches. In 1907, the National Primitive Baptist

Convention was organized in Huntsville at Saint Bartley, which was considered one of the denominations largest churches at the time.

Saint Bartley currently is located at 3020 Belafonte Ave., a place it has occupied since December 1965.

CHURCH OF THE GOOD SHEPHERD, MOBILE

The oldest historically black Episcopal Church in Alabama is the Church of the Good Shepherd in Mobile. It was established in 1854 after Trinity Church confirmed seven Blacks, who formed the new congregation. Freedmen and slaves had previously worshipped in Trinity’s gallery.

The church began holding its services in the Love and Charity Hall. The

congregation went on to purchase a site for its first church at the corner of Cedar and St. Michael streets. Members of White Episcopal churches helped by providing funds for the Church of the Good Shepherd. The church moved again in 1884. This time it relocated to an area around Warren and State streets.

Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd.

The first Black priest began serving Good Shepherd in 1896. Twelve years later in 1908, the church was incorporated through the state of Alabama. It was accepted as a parish of the Diocese of Alabama by 1914.

F.H. Threat was the first Black man ordained in the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama. He was first ordained a deacon in 1926 and later ordained a priest. The congregation survived the Civil War, the Great Depression, and a move in the 1960s from Mobile to Toulminville. It relocated after selling its property to Mobile County Schools to accommodate the expansion of the Dunbar Creative and Performing Arts Magnet School. In 1965, the newly built Church of the Good Shepherd received a design award for interior design at the American Institute of Architects Regional Convention.

STONE STREET BAPTIST CHURCH, MOBILE

Stone Street Baptist Church was established in Mobile, long before the Civil War and was placed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Stone Street Baptist Church, Mobile. Public Domain

In 1843, at a time when Blacks were not allowed to purchase land in Alabama, the trustees of Saint Anthony Street Baptist Church purchased land for use of the African branch of its church. About 25 years later, the title to the property at the southwest corner of Chestnut and Tunstall streets was transferred to the African American trustees of the Stone Street Baptist Church.

Richard Fields, who was known as “Uncle Dick,” was the first Black pastor of the congregation. As descendants of the last known slave ship to America settled in what was called Africatown, some of those residents joined Stone Street Baptist. The Clotilda descendants’ ancestry has been traced to Ghana and the kingdom of Whydah, Dahomey, now part of present-day Benin.

In 1870 the congregation moved to Cleveland Street. The name of that street was changed to Tunstall Street to honor former church pastor Charles A. Tunstall. The church was rebuilt in 1909 and renovated in 1931.

ST. LOUIS STREET BAPTIST CHURCH, MOBILE

Franklin Pierce was serving as America’s 14th president the year that St. Louis Street Missionary Baptist Church was organized. It was in 1853 that 10 members of the Stone Street Baptist Church decided to form another congregation.

St. Louis Street Baptist Church, Mobile. Public Domain

The first three pastors of the church were White, because Blacks couldn’t own property before passage of the 13th of Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

In 1856, the group’s White minister purchased a city lot on St. Louis Street. The congregation purchased the property from him in 1865, and bought an adjacent lot in 1868. That purchase included a small church, which was used for worship until they completed a new structure in 1872 at a cost of $24,000, according to the church’s history.

The Rev. C.A. Leavens was the first Black pastor of the church. He drew large crowds. The church gained a reputation for attracting professional and well-educated Black Baptists, according to published reports.

Among the early members was a former slave named Commodore Reed. He is believed to have been Mobile County’s first Black school teacher.

St. Louis Street placed emphasis on statewide missionary work. Congregational organizers were sent all over the state from the Mobile church and many Alabama congregations and pastors were established through this activity.

St. Louis Street Baptist played a role in establishing Selma University, a private, historically-Black Baptist college in Selma, established to prepare and strengthen leaders for churches and schools. In 1874, St. Louis Street hosted the 7th Colored Baptist Convention, which approved a resolution creating the institution. Trustees were selected, and the school opened four years later in St. Phillips Street Baptist Church in Selma.

St. Louis Street Baptist Church continued to supply leaders to the Black churches, including a president of the National Baptist Convention, D.V. Jemison, who served as pastor of the Mobile church in the late 1920s.

FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH, MONTGOMERY

The first congregation that would become First Baptist Church Montgomery organized in 1866. The former slaves had worshipped at the White First Baptist Church in Montgomery, before the Civil War ended. They had to sit in the balcony.

But in 1867, about 700 African Americans marched to an empty lot on the corner of Ripley Street and Columbus Street. There, they started Columbus Street Baptist Church, “the first ‘free Negro’ institution in Montgomery.”

First Baptist Church, Montgomery. Wikimedia Commons

The first pastor was Nathan Ashby, who also became the first president of the Colored Baptist Convention in Alabama, founded in his church on December 17, 1868. Ashby retired in 1870, after being struck by paralysis. He was followed, briefly, by J.W. Stevens, and starting in 1871, James H. Foster was the pastor for 20 years. Foster is credited with increasing membership from a few hundred to several thousand; his successor, Rev. Andrew Stokes, added even more.

Fire destroyed the first frame church. Between 1910 and 1915, the church was rebuilt under the leadership of Stokes. Members of the congregation were asked to each bring a brick a day to build it. This was the source for church’s nickname, the “Brick-A-Day Church.” The building was designed in the style of the Romanesque Revival by W.T. Bailey of Tuskegee University.

From 1952 to 1961, the church was led by civil rights activist Ralph Abernathy, a good friend of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., who preached a few blocks away, at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, from 1954 to 1960. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–1956), it was the location of mass meetings; Abernathy was a confidante of Edgar Nixon and quickly became involved with the boycott. After the boycott was over, and the buses in Montgomery were desegregated, occasionally buses would be ambushed and shots would be fired at them. One act of violence on January 10, 1957, was followed by several other violent acts. There were bombings at Montgomery’s Bell Street Baptist Church, the Mount Olive Baptist Church, the Hutchinson Street Baptist Church, and the First Baptist Church and its parsonage, which was the residence of Abernathy.

Raymond C. Britt, Jr., was charged with the bombing of the First Baptist

Church, and Henry Alexander and James D. York were charged with the

bombing of Abernathy’s house, but the city prosecutor dropped the charges.

On May 21, 1961, First Baptist Church was a refuge for the passengers on the Freedom Ride which met with violence at the Greyhound Bus Station in downtown Montgomery. The church was filled with some 1,500 worshippers and activists, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Fred Shuttlesworth, Diane Nash, and James Farmer. The building was besieged by 3,000 Whites who threatened to burn it.

In the basement, King, Abernathy, Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, James Farmer, and John Lewis, talked on the phone with United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, while bricks were thrown through the windows and tear gas came drifting in. The events of May 20-21, 1961, including the “siege of First Baptist,” played a crucial part in the desegregation of interstate travel.

Freedom riders and others who gathered at the church were forced to spend the night on church pews because of potential violence that lurked outside the doors of First Baptist. Eventually a deal was reached, allowing for the safe exit of everyone from the church around 4 a.m. on May 21.

The sanctuary of the First Baptist Church on North Ripley Street,

where Freedom Riders took refuge May 21, 1961. Alabama Tourism Bureau

MOUNT JOY BAPTIST CHURCH, TRUSSVILLE

Mount Joy Baptist Church in Trussville is the only Jefferson County Church founded by slaves and still operating with an active congregation. Mount Joy was organized in 1857 when slaves who attended First Baptist Church of Trussville were allowed to start their own church. Until that time, slaves attended the White church with their masters, but sat in the back and did not participate in the leadership of worship.

Initially, they were given permission to gather for worship in a log cabin on the plantation of Sam Latham in Trussville. The Rev. Wilson Fallin, author of Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama, states that the first name of the Mount Joy congregation was Latham Baptist Church, because of the location on the plantation.

Above: Alabama State Senator Shay Shellnutt and State Representative Danny Garrett present a proclamation to Pastor Larry Hollman of Mt. Joy Baptist Church in honor of its 160th anniversary, June 2017. The Birmingham Times

Mount Joy has battled through hard times to stay alive since its plantation beginnings. Fires destroyed the church’s historical records in 1914 and the church building in 1942. By the 1970s, membership was dwindling steadily.

Over the years, various factions in Mount Joy departed to start new

congregations. But in 1998, Mount Canaan Baptist of Trussville, which began after splitting from Mount Joy 84 years earlier, merged with the mother church. Then, in 2000, New Bethel Baptist merged with Mount Joy. That church had been comprised of 25 former Mount Joy members, according to published reports.

SIXTEENTH STREET BAPTIST CHURCH, BIRMINGHAM

Two years after Birmingham, an industrial city rich with coal and iron ore was founded in 1871, the First Colored Baptist Church of Birmingham opened its doors in 1873 near what would become a bustling downtown. As the city grew, so did the membership and prominence of this house of worship, a Gothic Revival structure built in 1884. That building was condemned by the city, and a new church and parsonage were built occupying its current location on Sixth Avenue North.

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was the spiritual home of many laborers, business owners and professionals. Included in the membership and serving on the Board of Trustees was the owner of one of the leading construction firms. T.C. Windham Construction began building the new church in March 1909. Members first used the fellowship hall in the basement for worship in 1911 before the entire building was completed.

This new church could seat 1,000 people, making it one of the largest meeting spaces in Birmingham. Sunday church services and special programs were regular events for the facility, but it often was transformed for community use. Major national African American educational, religious and political leaders and musicians spoke and performed, and local and national organizations gathered.

The church’s prominent location on major streetcar routes along Sixth Avenue in the heart of a city center residential district that was two blocks from the African American commercial hub along Fourth Avenue North, contributed to the popularity of the space for community use. Until A. G. Gaston constructed L.R. Hall in 1961, the only other large meeting spaces for African Americans in Birmingham were other churches, the Colored Masonic Hall and school auditoriums.

While the members of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church were aware of the Birmingham Movement, most had not participated in the marches, rallies and protests that began in June 1956 under the leadership of Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of Bethel Baptist Church, Collegeville. The movement expanded, and more than 60 churches were used at various times for rallies, strategy sessions, education and training. Sixteenth Street Baptist Church figured prominently in that lineup. Its proximity to downtown Birmingham, the Black business district and City Hall, made it an ideal location.

During the April-May joint campaign of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights led by Shuttlesworth and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference led by Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. King convinced Sixteenth Street Baptist Church pastor, Rev. John Cross, to allow the Movement to use Sixteenth Street’s facilities. According to reports of the Birmingham police who attended 45 meetings during April and May of 1963 and published reports for their chief, Sixteenth Street hosted seven Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights mass meetings during the Birmingham campaign.

In May of 1963, thousands of Birmingham children stood up to racial injustices in Birmingham. Many of them walked out of school. Some even climbed out of windows and walked miles to Sixteenth Street Baptist Church where they connected with other youths and received training and instruction for the task at hand – confronting discrimination in the South’s most segregated city.

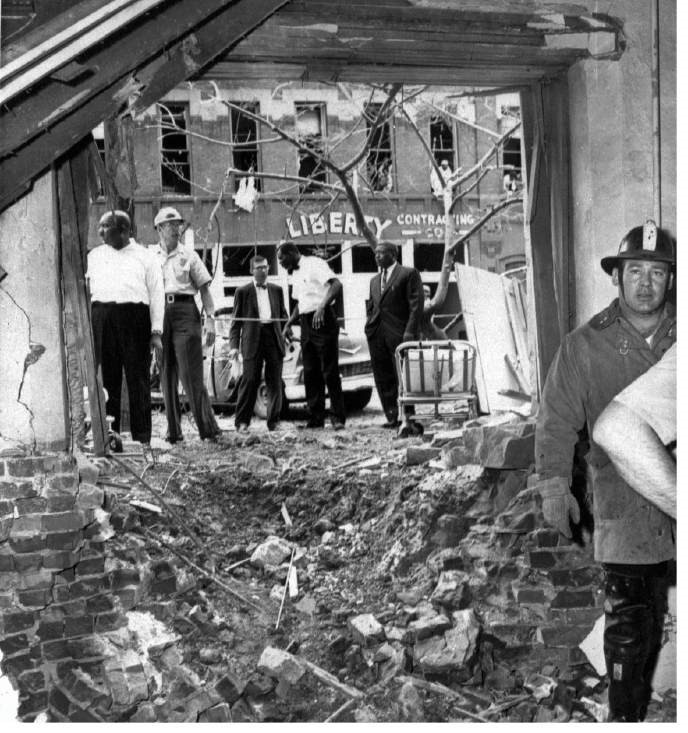

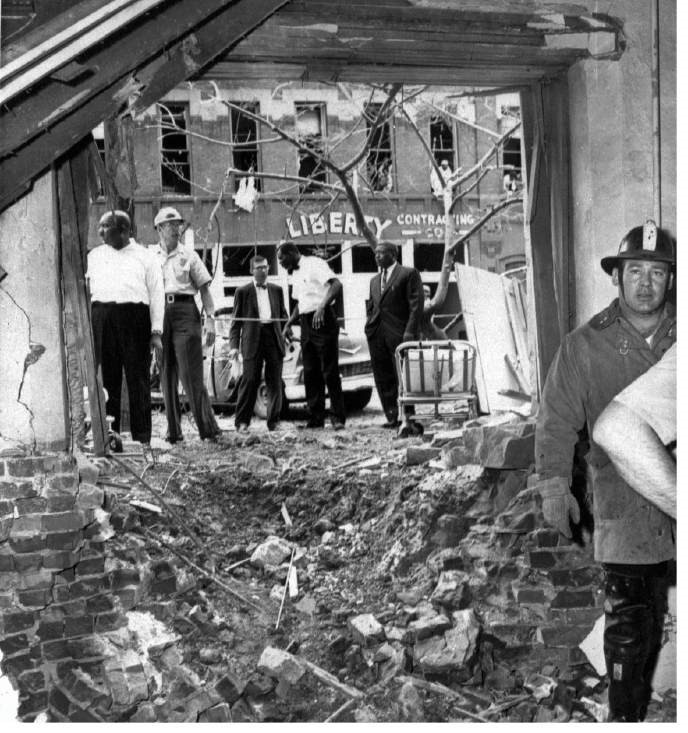

On September 15, 1963, Ku Klux Klan members, in an attempt to instill fear in African-Americans, planted a bomb at the church. The bomb exploded that Sunday morning and killed four little girls as they prepared to worship on Youth Day – Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Cynthia Morris Wesley and Carole Robertson.

The bomb blast destroyed the stairs. Three of the sanctuary windows, those closest to the bomb blast, were completely blown out, including some frames. The other sanctuary windows also sustained damage. However, the major thrust of the bomb imploded the brick and stone exterior wall and the foundation inward, forming a seven-by-seven-foot hole and thrusting debris into the women’s lounge where the girls had gathered. The church was renovated after the bombing. It also has had several other renovations over the years.

Above: Crater and other damage caused by the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, September 15, 1963. Associated Press

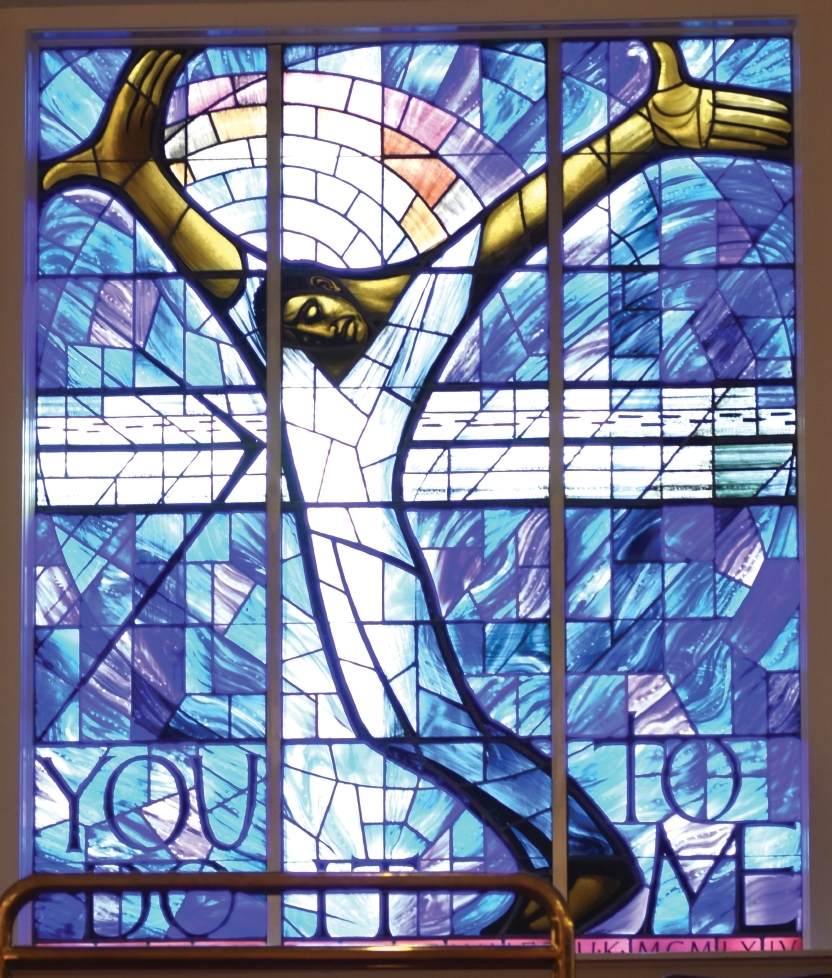

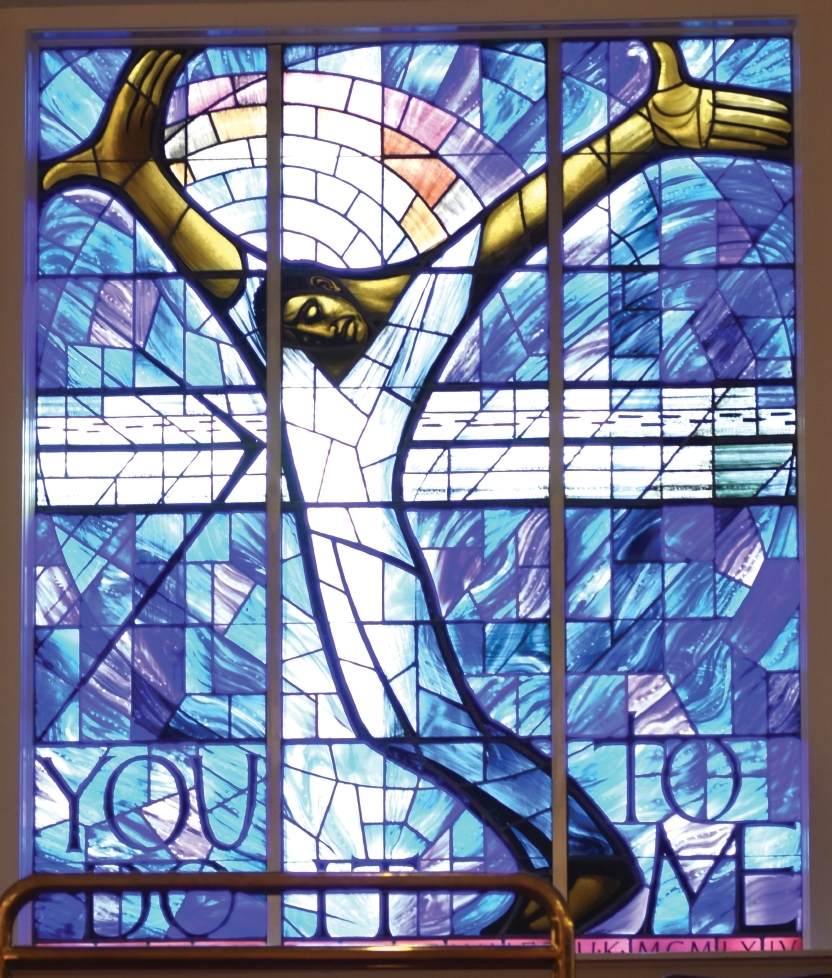

Right: This stained-glass window was donated to

Sixteenth Street by the people of Wales after the church was bombed in 1963. The Birmingham Times

Above: Crater and other damage caused by the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, September 15, 1963. Associated Press

Below: This stained-glass window was donated to Sixteenth Street by the people of Wales after the church was bombed in 1963. The Birmingham Times

In 1980, the National Register of Historic Places listed the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. The nomination prepared by the Birmingham Historical Society cited the church’s role in the Birmingham campaign and the bombing.

Before leaving office in 2017, President Barack Obama signed a proclamation designating the Birmingham Civil Rights District a national monument. Sixteenth Street Baptist continues to serve the community while welcoming visitors regularly from around the world.