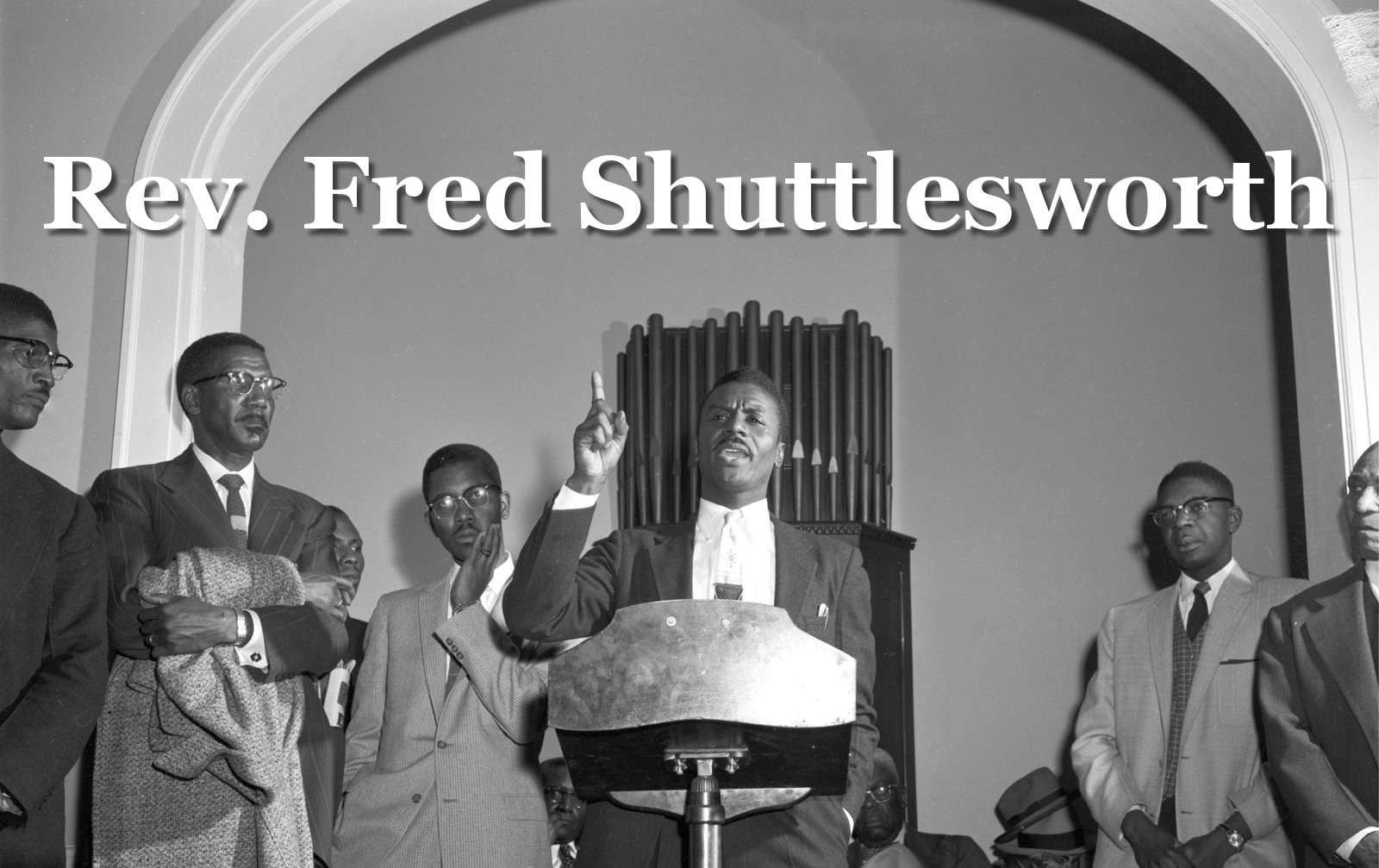

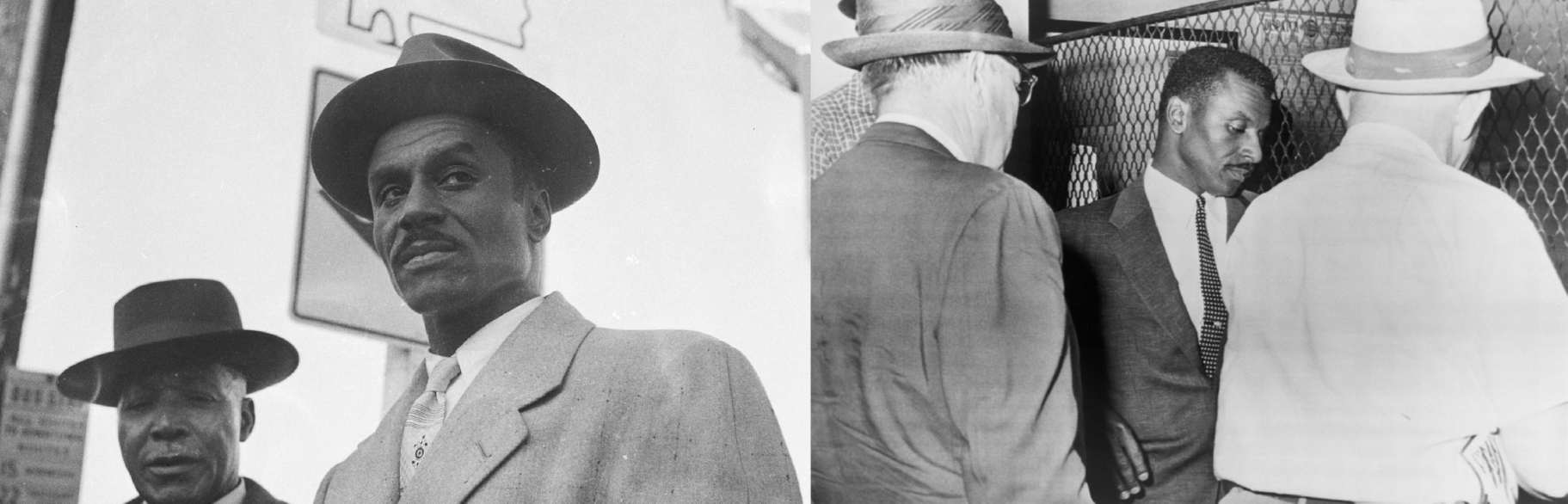

THE REVEREND FRED LEE SHUTTLESWORTH WAS BORN ON MARCH 8, 1922, in Montgomery County, Alabama, raised by his mother, Alberta Robinson Shuttlesworth and his step-father, William Nathan Shuttlesworth, a farmer, in rural Oxmoor, Alabama.

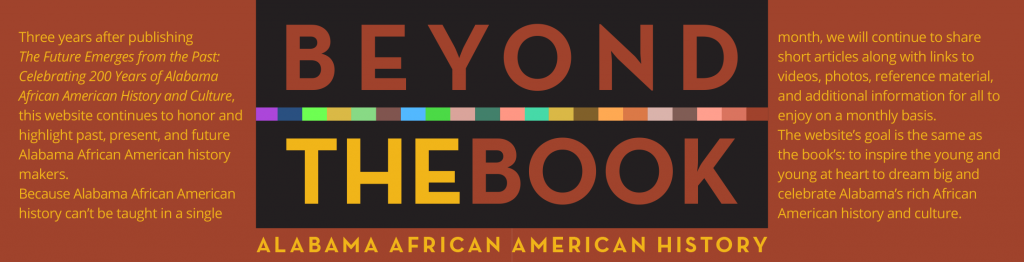

A former truck driver who studied religion at night, Rev. Shuttlesworth became pastor of Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1953 and soon emerged as an outspoken leader in the struggle for racial equality.

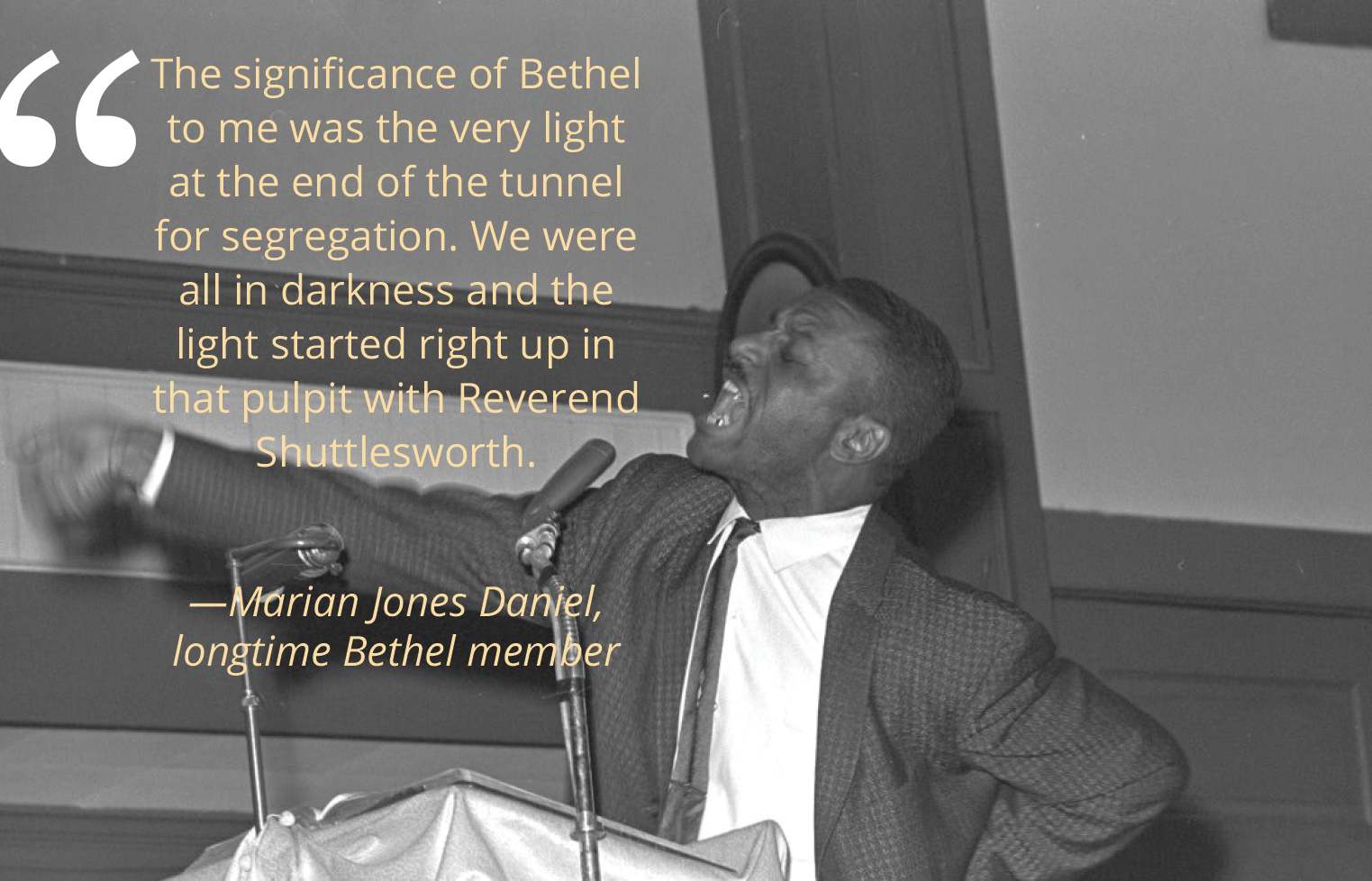

“My church was a beehive,’’ Rev. Shuttlesworth once said. “I made the movement. I made the challenge. Birmingham was the citadel of segregation, and the people wanted to march.’’

In his 1963 book Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King Jr. called Rev. Shuttlesworth “one of the nation’s most courageous freedom fighters . . . a wiry, energetic, and indomitable man.’’

“I went to jail 30 or 40 times, not for fighting or stealing or drugs,’’ Rev. Shuttlesworth told grade school students in 1997. “I went to jail for a good thing, trying to make a difference.’’

Alabama’s first black federal judge, U.W. Clemon, said Rev. Shuttlesworth flung himself at injustice well knowing he could be killed at any moment. “He was the first Black man I knew who was totally unafraid of white folks,’’ said Clemon, who retired from the bench and is now a privately practicing attorney.

Historian Horace Huntley of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute said Shuttlesworth personally challenged just about every segregated institution in the city — from schools and parks to buses, even the waiting room at the train station. “They had a white section and a colored section. Fred and his wife bought tickets, and they sat in the white section,” Huntley said. “That was revolutionary for Birmingham of the 1950s.”

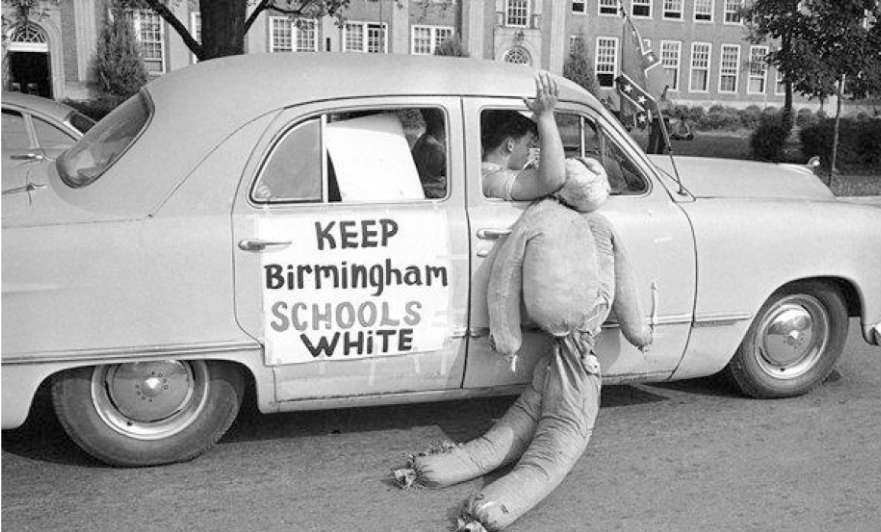

Above: A dummy is dragged in effigy past Birmingham’s West End High School, September 1963 (AP)

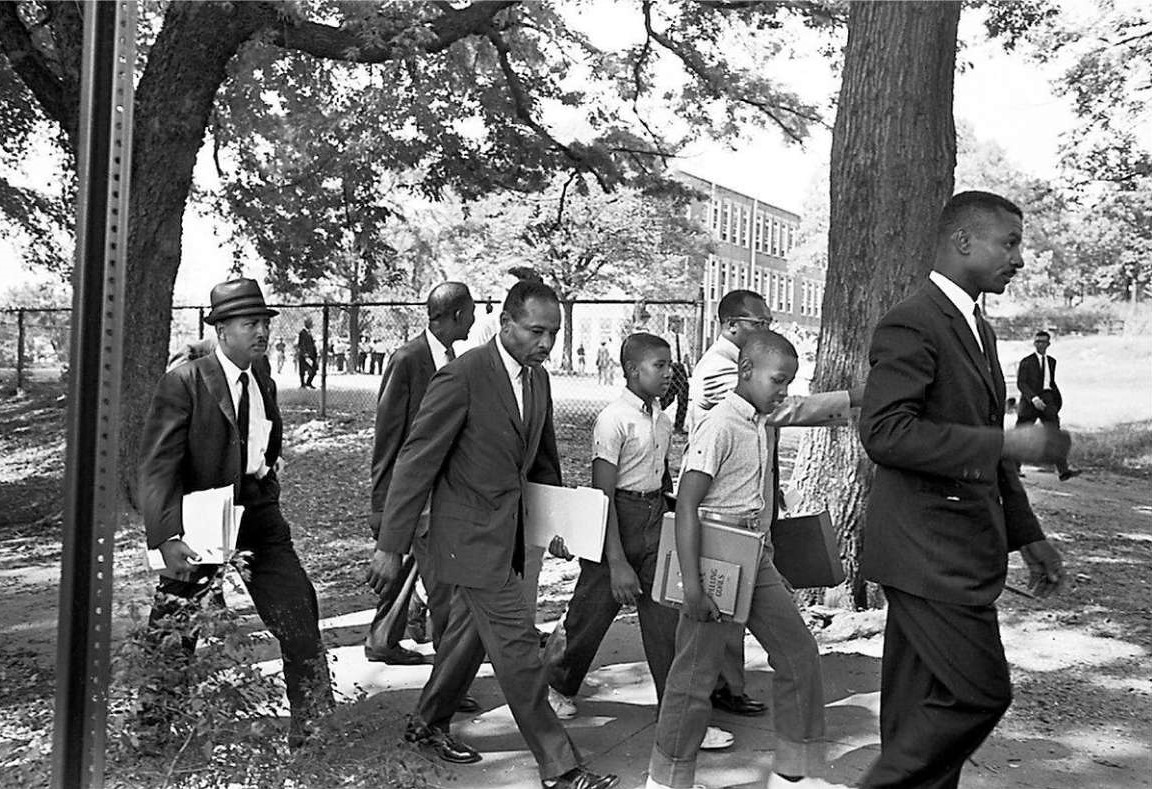

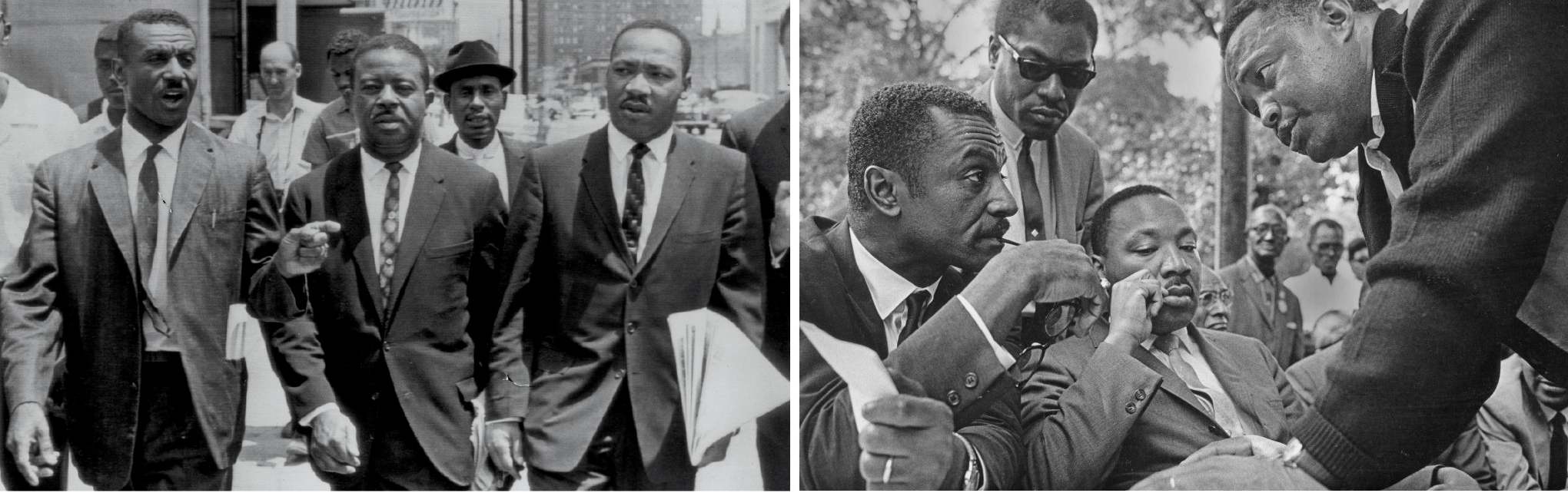

Right: Fred Shuttlesworth, Dwight Armstrong (age 11), Floyd Armstrong (age 10), James Armstrong, Birmingham attorney Oscar Adams, Jr., and NAACP lawyer Constance Motley leaving Graymont Elementary School after the boys were denied registration, September 9, 1963 (six days before the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing). (Al.com)

Top photo: A dummy is dragged in effigy past Birmingham’s West End High School, September 1963 (AP)

Bottom photo: Fred Shuttlesworth, Dwight Armstrong (age 11), Floyd Armstrong (age 10), James Armstrong, Birmingham attorney Oscar Adams, Jr., and NAACP lawyer Constance Motley leaving Graymont Elementary School after the boys were denied registration, September 9, 1963 (six days before the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing). (Al.com)

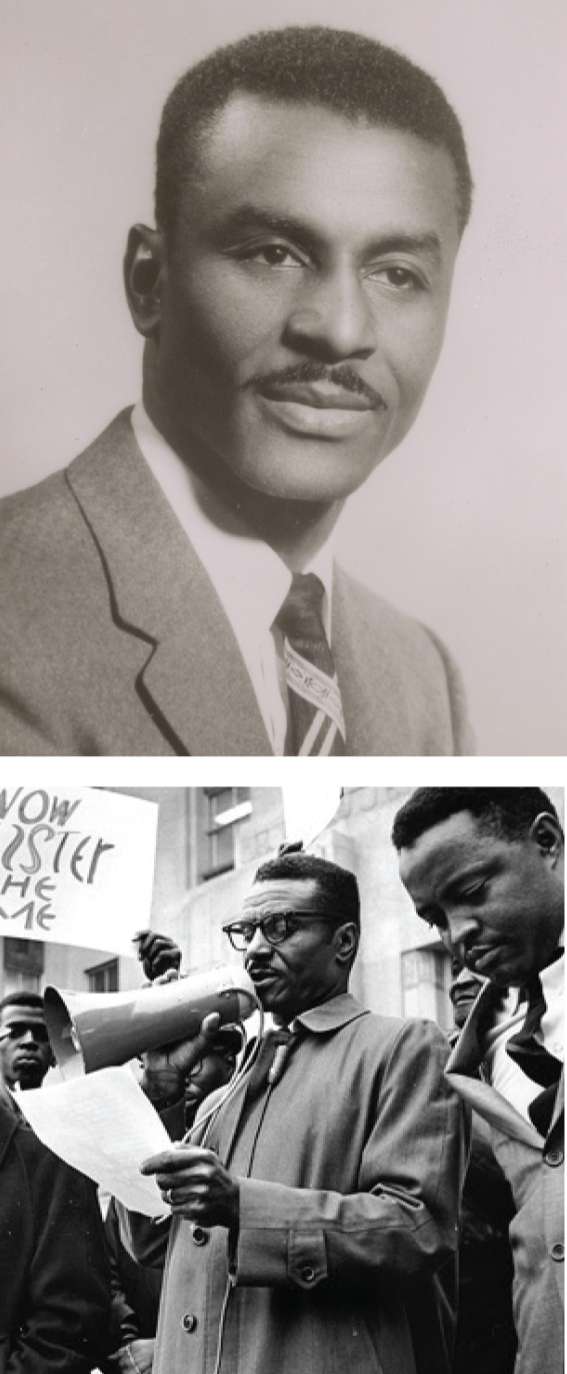

In response to the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, state officials conspired to prevent future outbreaks of Black protest by trying to silence the NAACP. John Patterson, the Alabama attorney general and soon-to-be governor of the state, led the effort. Using a loophole in state law, he managed to shut down local NAACP branches. As the nation’s leading civil rights organization, the absence of the NAACP created a noticeable void in the Black community. In Birmingham, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), founded on June 5, 1956, filled this empty space, with Fred Shuttlesworth heading the organization.

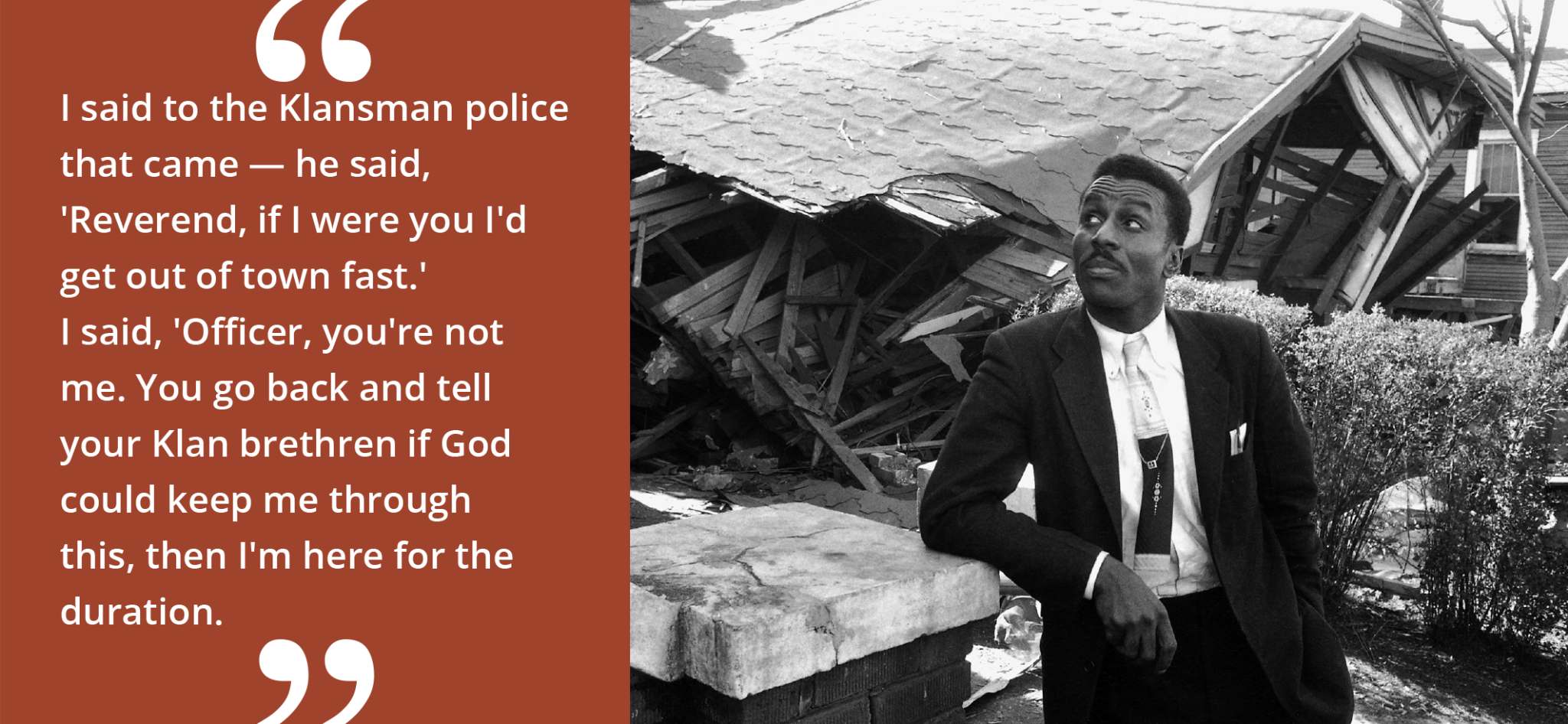

Always at the forefront of the fight for equality, Shuttlesworth’s activities came with a price. He was repeatedly jailed. His home and church were bombed on Christmas Day, 1956. But Shuttlesworth didn’t back down.

Fred Shuttlesworth outside Bethel Baptist Church and his bombed house next door, Birmingham, c. 1950s.

“Instead of running away from the blast, running away from the Klansman,” Shuttlesworth told the documentary Eyes on the Prize, “I said to the Klansman police that came — he said, ‘Reverend, if I were you I’d get out of town fast.’ I said, ‘Officer, you’re not me. You go back and tell your Klan brethren if God could keep me through this, then I’m here for the duration.’ “.

In 1957, he was beaten by an angry mob for trying to enroll his daughters in Birmingham’s all-white Phillips High School. That same year, he would join with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, Bayard Rustin and others to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He would also assist the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) in organizing the Freedom Rides in 1961.

“They really thought if they killed me — the Klansmen did — that the movement would stop, because I remember they were saying, ‘This is the leader. Let’s get this SOB; if we kill him it will all be over,’ ” Shuttlesworth recalled in a 1987 interview with NPR’s Susan Stamberg. After being struck with brass knuckles and bicycle chains, Shuttlesworth said, the doctor was amazed he wasn’t in worse shape. “I said, ‘Well, doctor, the Lord knew I lived in a hard town, so he gave me a hard head,’ ” he said.

It was on display every time he went head-to-head with Birmingham’s racist police commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor. “He would lead demonstrations, and he would call Bull Connor and say, ‘Bull, I will be on such and such corner; if you want to be part of history, be there,’ ” Huntley said.

Shuttlesworth and the ACMHR fought admirably to end segregation in the “Magic City” but made very little headway on their own. The slow pace of progress over the next several years eventually led them to invite outside organizers to help them with the struggle. Martin Luther King Jr. was among those who would answer the call.

A 1961 CBS documentary called Shuttlesworth the “man most feared by Southern racists.” It was Shuttlesworth who asked Attorney General Robert Kennedy to protect freedom riders, and the last thing Connor wanted was federal intervention.

Birmingham Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, c. 1960s.

“You know those Kennedys up there in Washington — that ole Bobby Sox and his brother, the president — they’d give anything in the world if we had some trouble here,” Connor said at the time.

And trouble was coming. Shuttlesworth was laying the groundwork for something bigger. In 1963, he persuaded the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to bring the civil rights movement to Birmingham after a dispirited campaign in Albany, Ga. Shuttlesworth told Eyes on the Prize he thought Birmingham could make a difference.

“I said, ‘I assure you if you come to Birmingham, this movement can not only gain prestige, but really shake the country,” he said. He was right — prophetic, some said. King launched “Project C,” for confrontation.

Shuttlesworth convinced Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC to focus civil rights efforts in Birmingham.

Connor unleashed police dogs and turned fire hoses on the young demonstrators. When that didn’t turn them back, he put them behind bars. More than 2,500 people were jailed, including the children. Shuttlesworth was hospitalized during the 1963 demonstrations as a result of being attacked by the water cannons to which Connor resorted in an attempt to break up the nonviolent demonstrations.

The shocking images appeared on the nightly news. President John Kennedy

declared the struggle for civil rights a moral issue.

Statue of Shuttlesworth at the Birmingham

Civil Rights Institute.

In 2001, Shuttlesworth received the Presidential Citizens Medal from President William J. Clinton, the second-highest civilian award in the United States, second only to the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 2004, Shuttlesworth received the Jefferson Award, given annually to those whose extraordinary public service inspire others to action.

In July 2008, the Birmingham Airport Authority voted to honor Shuttlesworth by renaming the city’s airport, the largest in the state of Alabama, in his honor. His alma mater, Alabama State University, also named its main cafeteria, the Fred L. Shuttlesworth Dining Hall, in his honor.

The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute annually bestows the Fred L. Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award, named after its inaugural honoree in 2002. Past awardees include Myrlie Evers-Williams, Angela Davis, Andrew Young, Dorothy Cotton and John Lewis.

Birmingham Shuttlesworth Airport

Shuttlesworth was named president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 2004, but would resign later that year.

Above left: Birmingham Shuttlesworth Airport

Above right: Shuttlesworth was named president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 2004, but would resign later that year.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

A Walk to Freedom: The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the Alabama

Christian Movement for Human Rights, 1956-1964 (1998) by Marjorie L. White

A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth (2001) by Andrew Manis