Bessie Coleman (c. 1923) was the first African-American woman and the first Native American to hold a pilot license, earning her license from the Fédération Aéronautique International (France) in 1921, and was the first Black person to earn an international pilot’s license.

It all started with Bessie Coleman.

Though she was told “no” over and over again when she applied to flying school because they said black women had no place in aviation, she said “I refused to take ‘no’ for an answer.”

Six decades after our Tuskegee sisters broke the barrier in the military, Marine Captain Vernice Armour became the first female African American combat pilot in 2003.

Captain Vernice Armour became the Marine Corps’ African-American woman pilot. Armour then completed two tours in Iraq, becoming America’s first woman combat pilot. (Photo: Heather Walters)

Willa Brown Chappell was instrumental in training more than 200 students who went on to become the legendary Tuskegee airmen.

Willa Beatrice Brown was born on January 22, 1906 in Glasgow, Kentucky. A pioneering aviator, she earned her pilot’s license in 1937, making her the first African-American woman to be licensed to fly in the United States.

Janet Harmon Bragg

The first black woman to receive a commercial pilot’s license. Bragg was born March 24, 1907 in Griffin, Georgia to Samuel Harmon and Cordia Batts. She attended Episcopal boarding schools and after graduation, pursued a nursing degree at Spellman College in Atlanta, where she qualified as a registered nurse in 1929 before moving to Chicago to work at Wilson Hospital.

In 1933, having always been interested in learning to fly, Bragg became the only woman in her class when she enrolled at Aeronautical University in Chicago under the instruction of Cornelius Coffey and John C. Robinson.

Mural honoring Janet Harmon Bragg, the first African American woman to hold a commercial pilot’s license, Griffin, Georgia. (Credit: Griffin + Spalding Business and Tourism Association)

Mildred Hemmons Carter was one of the first women to earn her pilot’s license through the Civilian Pilot Training Program, but was asked to withdraw her application from the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) because of her race. She then applied for the Tuskegee Airmen, the group of Black combat pilots, but was rejected this time because of her gender. She was finally recognized as a WASP 70 years later, and took her final flight at age 90!

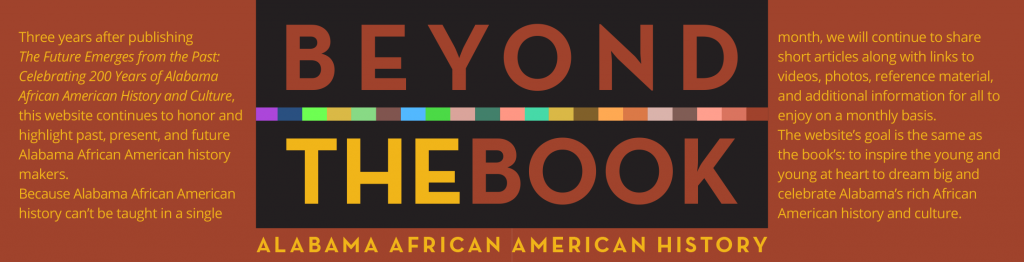

Mildred Hemmons Carter

Mildred Carter’s rejection letter from the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots was cold, plainly stated and infuriating. Mrs. Carter, then Mildred Hemmons, was among the first women to earn a pilot’s license from Tuskegee Institute’s civilian air training school. The school became legendary with the success of the Tuskegee Airmen in World War II.

Female pilots were prohibited from flying in combat then, but after becoming licensed in 1941, Mrs. Carter felt she was well on her way to a career in aviation. Then the letter arrived.

“It stated that I was not eligible due to my race. It left no doubt,” says the diminutive and elegant Tuskegee-born woman with the brilliantly engaging eyes. “I didn’t keep it. I didn’t keep any of that stuff. I didn’t want to look at it, to deal with it.”

A MIDAIR COURTSHIP

– Wayne Drash/CNN 2012 –

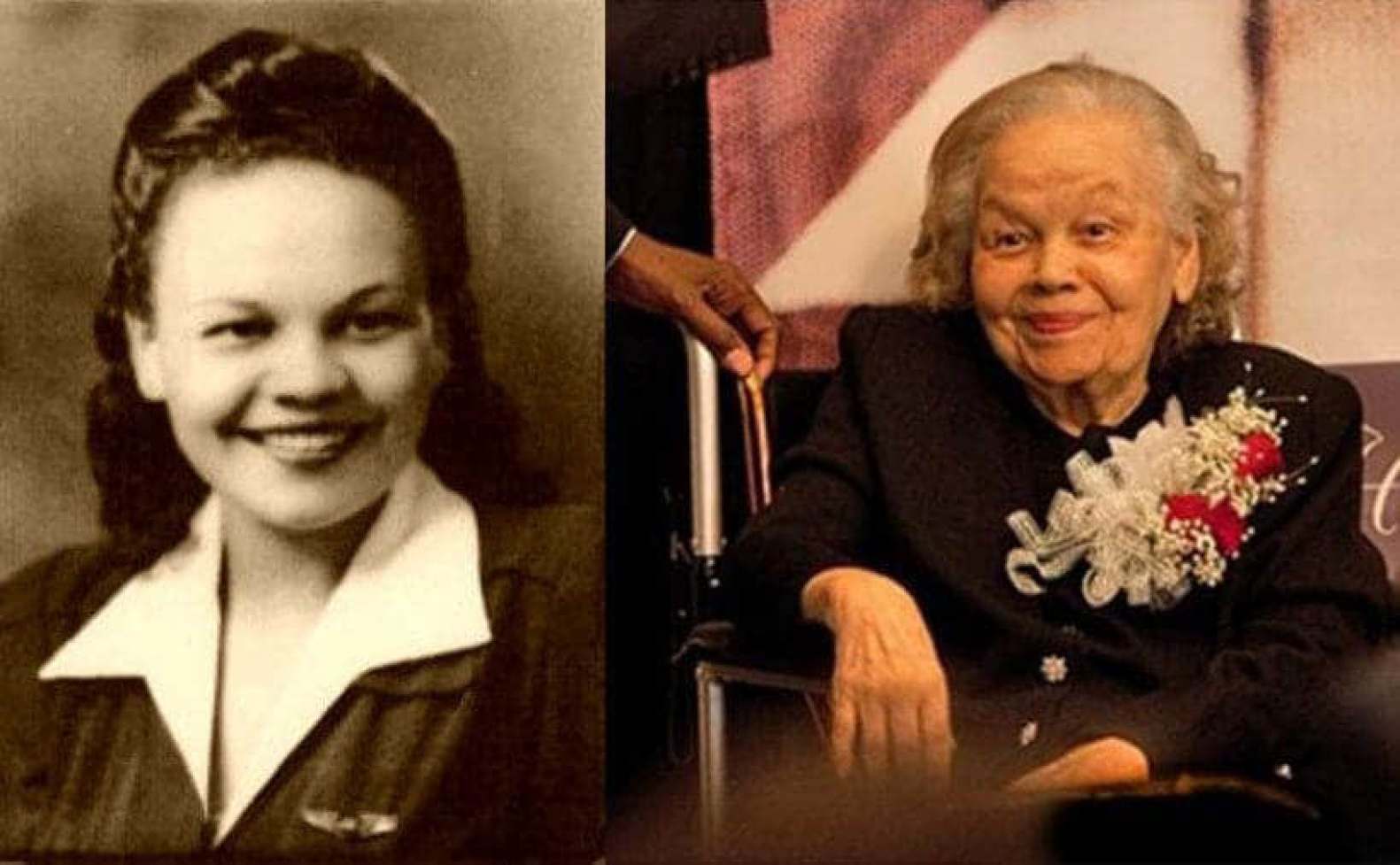

Herbert Carter and Mildred Hemmons had no time for dating in the early months of 1942.

He was training to become a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, the nation’s first military program for African-American pilots. She was the bold, daring woman who caught his eye. At 18, she’d become the first black woman in Alabama to earn a pilot’s license. She had hopes of becoming a military pilot, too.

The two would become known as the first couple of the Tuskegee Airmen. Herbert would go on to earn the rank of lieutenant colonel in a 27-year Air Force career.

He remains one of the few men in U.S. history to be a fighter pilot and a squadron maintenance chief, a designation he notes with pride. Rarely is a pilot also charged with making sure the squadron’s planes are airworthy.

Flying was intoxicating. It provided Herbert and Mildred a sense of freedom — to be themselves, to dream big. The in-your-face racism of the segregated South was gone, if only for a while. In the air, the sky was literally the limit.

It takes pioneers to force change. Herbert and Mildred would play their part in the years ahead. But in those early days, they didn’t see themselves as trailblazers. They were young and in love.

They’d pick a time to meet. Their rendezvous point: 3,000 feet above a bridge at Lake Martin, 25 miles away. He’d be flying a repaired AT6 trainer. She’d be in a much slower Piper J-3 Cub.

The picture at right depicts the Carter’s rendezvous point: 3,000 feet above a bridge at Lake Martin, 25 miles away. “When I’d get to Lake Martin, I’d see this bright yellow Cub putt-putting along,” Herbert said. “I’d be real proud: She was on time and on target.” (Illustration/Jay Ashurst)

Air(wo)man Discovered and Honored

https://www.nps.gov/articles/tuskegee-airwoman-amelia-jones.htm

The forgotten role of the Tuskegee Airwomen during World World II

https://face2faceafrica.com/article/the-forgotten-role-of-the-tuskegee-airwomen-during-world-world-ii

The Woman Whose Tireless Efforts Helped Launch The Famed

Tuskegee Airmen

https://www.zenger.news/2022/03/31/the-woman-whose-tireless-efforts-helped-launch-the-famed-tuskegee-airmen/

Three women to thank for Tuskegee Airmen existence …

https://www.march.afrc.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/167712/three-women-to-thank-for-tuskegee-airmen-existence/

Women of Tuskegee supported famed Black pilots

https://www.cnn.com/2012/02/02/us/women-of-tuskegee-supported-famed-black-pilots/index.html