The concept of building small rural schools for Blacks originated with Booker T. Washington and the staff at Tuskegee Institute’s Extension Department at the start of the 20th century.

Julius Rosenwald, CEO of Sears and Roebuck, invested in this rural “school construction campaign” substantially, helping to construct more than 5,000 buildings in 883 counties in 15 states between 1912 and 1932, filling a desperate need.

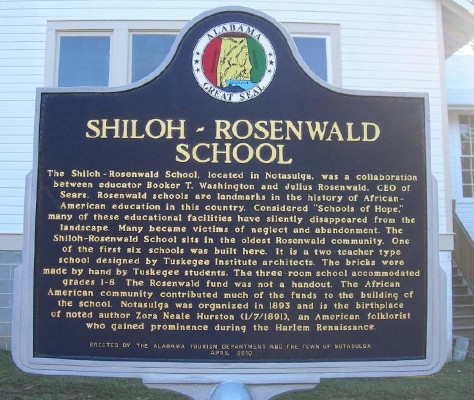

The Shiloh–Rosenwald School sits in the oldest Rosenwald community. It was one of the first six Rosenwald Schools built in the United States. The school was closed in 1964 and reopened, after renovation, as a permanent museum in 2010.

Alabama’s 1875 constitution imposed school segregation, and the 1901 constitution subsequently allowed local school boards to distribute state school funds, much of which were diverted to White schools. Therefore, Blacks often held classes in rented homes, churches, lodge halls, or in abandoned shacks and houses. In 1910, two years before the Rosenwald School building program began, 61 percent of the Black schools in Alabama were housed in such structures. In the same year, only about 60 percent of Black children between ages six and 14 in 16 southern states attended school. Up until 1910, the school term for Blacks in Alabama was less than five months.

Beginning in 1904, Washington and Tuskegee extension director Clinton J. Calloway used philanthropic funding to develop a public school building program for Blacks in Macon County. Over the next five years, Washington and Calloway used funding from Standard Oil baron Henry Huttleson Rogers to construct 46 schools for Blacks in Macon County. When Rogers died in 1909, Washington began looking for another major benefactor who would invest in and help expand the rural school construction program.

In 1911, while speaking in Chicago, Washington met Julius Rosenwald, one of the most famous and influential businessmen of his time, who had recently expanded his philanthropy to African American causes.

Washington added Rosenwald to Tuskegee’s Board of Trustees and began to cultivate him as a successor to Rogers in the school building project. The two men began exchanging views about a new rural school construction program that would combine outside philanthropy with community self-help to leverage public investment in Black education.

Under the direction of the Extension Department of Tuskegee Institute, Washington and Calloway constructed six experimental schools in and around Macon County. These were built to designs by Robert R. Taylor, staff architect and director of industries at Tuskegee, and were completed the spring of 1914. The success of these first experimental schools convinced Rosenwald to support an expanded program that would be overseen by Tuskegee.

The term “Rosenwald School” became an identifying label in which “Rosenwald” served as an adjective to distinguish it from other “Colored” schools. No doubt some people mistakenly thought that the Rosenwald designation meant that Julius Rosenwald had paid for the building in its entirety.

Although Rosenwald’s contribution was substantial, the fund generally contributed an average of about one-sixth of the total monetary cost of the building, grounds, and equipment. Most of the cash, raised either through private contributions or public tax funds, came from rural Black citizens themselves. Their additional contributions in the form of land, labor, and building materials were also substantial. Generally, too, they provided ongoing maintenance.

This type of school building construction was unprecedented in the development of education in the South. Rosenwald schools meant better schoolhouses, trained teachers, improved health conditions, and in some cases, bus transportation. The schools were frequently the most attractive public building in the district and became a social center for Blacks.

The original school was built according to the Tuskegee design by Tuskegee Institute architects. It was a two-room, two-teacher school. Tuskegee developed a set of standardized plans in a pamphlet entitled The Negro Rural School and its Relation to the Community, from which communities could choose an appropriate design. One common feature, and a character-defining element in identifying Rosenwald schools today, was high, spacious windows grouped to maximize natural lighting and air circulation. The plans also addressed sanitation and moisture control.

Take this under consideration from the Shiloh Community Restoration Foundation website: “Imagine an elementary school without electricity, indoor plumbing or a heating or air conditioning system, but with dedicated parents and teachers, children never late for school, used text books, used desks, well water, pot belly stoves, outhouses, a piano and a determination to be the best. First, second and third grade was taught in one classroom. Fourth, fifth and sixth grade was taught in other area of the room that was separated by an accordion door. The school motto: Good, better, best never let it rest until the good gets better and the better is best. Don’t settle for anything less.”

Children walked to school on unpaved dirt roads. The excitement of an educational opportunity was contagious and celebrated by the parents. A typical school day began at 8 a.m. after children had completed early morning chores, such as feeding chickens or milking cows. After the school day ended at 3 p.m., children performed chores such as chopping or picking cotton and then completing daily homework. In addition to the mandatory three Rs — reading, ‘riting’ (writing) and ‘rithmetic’ (arithmetic), every child gained invaluable lessons regarding respect, responsibility and resolve.

Children were exposed to weekly movies for a fee of 10 cents, songs played on the piano and school assemblies. The original school featured outdoor restrooms or out houses for boys and girls. Drinking water was provided by a well that was constructed atop a hill adjacent to the school. Recreation consisted of a playground in the backyard area with a swing set and space to play softball, horseshoes, hop scotch and jump rope.

Booker T. Washington died in 1915, but the school building program continued to be administered by Tuskegee until 1920. At that time Rosenwald decided to establish a central administration at Nashville, Tennessee, under the direction of S. L. Smith. Smith updated Tuskegee’s designs and provided additional plans in a second publication entitled Community School Plans.

To measure the impact of the Rosenwald fund on the education of Black southerners, one need only look at the statistics. In 1932 a quarter of all Black school children in the South were taught in Rosenwald Schools. And when the building program ended in the same year, one in five African American school buildings in the South was a Rosenwald school.

As rural schools began to close in the 1950s and 1960s, especially after integration, many communities held onto their Rosenwald schools as markers of communal spirit. Today the surviving Rosenwald schools, teachers’ homes, and vocational training buildings symbolize both the vision of Washington and Rosenwald and, more generally, the historic struggle of Blacks for educational opportunities in a segregated South.

RESOURCES

- List of Rosenwald schools. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Rosenwald_schools

- Rosenwald Schools: 100 Years of Pride, Progress, and Preservation. https://www.alabamaheritage.com/from-the-vault/rosenwald-schools-100-years-of-pride-progress-and-preservation

- Shiloh-Rosenwald School in Notasulga. http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/m-8113

- Shiloh Community Restoration Foundation. https://shilohcommfound.com/