By Nettie Carson Mullins

In 1961 there was a sound like no other developing in the small town of Muscle Shoals, Alabama at a music studio called FAME.

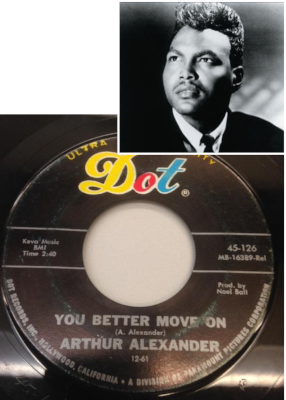

A local African American bellhop by the name of Arthur Alexander had a hit record, “You Better Move On.” It was the first of a string of Rhythm and Blues (R&B) hits recorded at FAME by legendary African American artists such as the “Queen of Soul” Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, and Clarence Carter, just to name a few.

For over a century, this cluster of Alabama municipalities (Florence, Muscle Shoals, Sheffield, and Tuscumbia) called the Quad-Cities, or the Shoals, has produced some of the most outstanding American music in history. The Shoals forms a geographic musical triangle with Memphis and Nashville. The music from this region has had an enormous impact on the whole of American music scene.

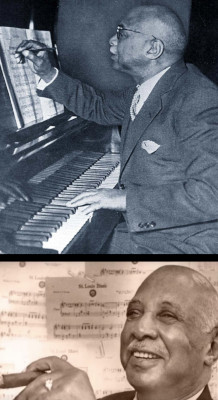

Beginning with William Christopher (W.C.) Handy, the Father of the Blues, who was born in Florence, Alabama. He was one of the most influential composers in the United States. Handy did not create the blues genre but he was the first to publish music in the blues form, thereby taking the blues from a regional music style called the Delta Blues, with a limited audience, to a new level of popularity.

As an African American composer, he changed the course of popular music by integrating the blues style into the then-fashionable ragtime music. Handy’s most famous composition was the popular masterpiece “The St. Louis Blues” which he published in September 1914. It was one of the first blues songs to succeed as a pop song and remains a fundamental part of the jazz musicians’ repertoire.

The Shoals was also the home to Sam Philips (1923-2003), the founder of the well-known studio Sun Records, which launched the careers of Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis.

This cozy community, the Shoals, seemed to be an unlikely place for a celebrity crowd in the 1960s and 70s. The nicest hotel in the Quad-Cities was the Holiday Inn. When musical artists came to town to record in the studio, they were sometimes housed in mobile homes at a local trailer park. But the music and the musicians kept coming to encounter the Muscle Shoal soul sound.

What is the Muscle Shoals soul sound? The Muscle Shoals style fused hillbilly, blues, rock’n’roll, soul, country, and gospel, to create a sound that cherry-picked the best features of each to forge something new. They close-mic’d the kick drum, and the FAME recordings pumped with heavy bass and drums. They were masters at creating this Southern combination of R&B, soul, and country music as back up for Black artists, who were often in disbelief to learn that the studio musicians were white. Artists from around the world found their sound in the studios of the Shoals.

So, what’s so special about this place? Album executive producer, FAME co-owner, publisher, and son of the late executive producer Rick Hall, Rodney Hall attributes it to the sound his father pioneered. “The sound is one-of-a-kind,” he explains. “It comes down to hooks, groove, quality, and vocals. The sound rooms are obviously a part of it. Mostly, it’s the people and the songs though. My father used musicians like a paintbrush. If a track called for a certain feel, he would hire the right players for that feel. We’ve got the Swampers and a pool of musicians here who have worked together for years. They also have young guys learning under them. When young artists hear about all of the music that came out of here over the past five decades, they want to check it out. Everyone always says it feels like home.”

The Swampers guitarist Jimmy Johnson states that the Muscle Shoals Sound musicians may have grown up in the South, but their influences came from artists like Chuck Berry, Ray Charles, and Bo Diddley. When people inquired why they sound Black, Johnson said that was the greatest compliment anyone could give them.

Why did it take so long for word to get out about Muscle Shoals? One reason is that the Muscle Shoals area is in the middle of nowhere. There was not a large media market nearby. There are no interstates, not many chain restaurants, and it was a dry county until the 1980’s—meaning no alcoholic beverages could be purchased. The other reason is FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound Studios weren’t big record labels like Motown. “We were a behind-the-scenes production house. For years, the only way people knew about us was by reading album liner notes,” Hall revealed.

Why did it take so long for word to get out about Muscle Shoals? One reason is that the Muscle Shoals area is in the middle of nowhere. There was not a large media market nearby. There are no interstates, not many chain restaurants, and it was a dry county until the 1980’s—meaning no alcoholic beverages could be purchased. The other reason is FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound Studios weren’t big record labels like Motown. “We were a behind-the-scenes production house. For years, the only way people knew about us was by reading album liner notes,” Hall revealed.

Muscle Shoals sound isn’t only about music. The story is more remarkable because history’s greatest African American musical legends traveled into the Deep South at a perilous time in American history under the shadow of the Civil Rights Movement, the Ku Klux Klan, racial tension, Jim Crow, and discrimination. In 1963 Alabama Governor George C. Wallace had declared “Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! And segregation forever!” Producer Rick Hall didn’t care about that. He was colorblind and just loved good music.

This inspirational sanctuary made a stand for equality by uniting African Americans and white musicians in the studio on many immortal recordings and soundtracks. Producer Rick Hall welcomed artists with open arms. Hall embraced them and provided a comfortable and creative place where they could bare their souls on their records. Hall’s wife Linda stated that there were no racial problems like the Civil Rights struggles that were occurring down in Birmingham and other Southern cities. She said, “It just didn’t happen in the Shoals.”

Rick Hall recalled integrating local restaurants in the shoals by dining with visiting artists like Otis Redding. He stated that it was dangerous and hard, but it had to be done. Hall and his musicians, known as the Swampers, loved and wanted to record African American soul music. According to Hall, “I loved that style of music and I wanted to be like them.” Hall knew that African Americans had reservations about coming to Alabama. He knew he had to convince them that they would be comfortable and safe.

So, where did the Muscle Shoals’ magic begin? In 1958 Rick Hall, Billy Sherrill, and Tom Stafford created the Florence Alabama Music Enterprise above a city drugstore in Florence. Then in 1960 Rick Hall took over as the sole owner and abridged the name to the acronym F.A.M.E. and moved the group across the river to Muscle Shoals. It was here that “Muscle Shoals sound” had its first international success with the R & B artist, Arthur Alexander, and his hit song “You Better Move On.”

Hall took the money he earned from this hit song and $10,000.00 he borrowed from Jerry Wexler, the vice president of Atlantic Records, and built a new studio. As artists entered the studio of FAME, the sign above the doorway read: “Through these doors walk the finest musicians, songwriters, artists, and producers in the world!” The next R&B singer to have a hit record from this studio was Leighton, Alabama native Jimmy Hughes with “Steal Away.” And success didn’t stop there. FAME has welcomed the Who’s Who of music royalty and legends such as Etta James, Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin, Alicia Keyes, Jennifer Hudson, Stephen Tyler, Jason Isbell, and Demi Lavato.

At FAME, Wilson Pickett recorded “Mustang Sally,” “Funky Broadway,” and “Hey Jude.” Clarence Carter recorded “Slip Away,” “Too Weak to Fight,” and his Grammy-nominated song “Patches.”

After four years with no success at Columbia Records, Jerry Wexler of Atlantic records brought Aretha Franklin to FAME. Her very first cut at FAME was a million-selling, double-sided smash hit called “I Never Loved a Man” and “Do Right Woman.” The album won a Grammy for “Album of the Year.”

R&B artist Otis Redding brought Arthur Conley to FAME and recorded “Sweet Soul Music” and “You Left the Water Running.” By 1970 FAME had on their roll Candi Staton, Clarence Carter, Arthur Conley, and The Osmonds. The Osmonds were five Caucasian brothers from Ogden, Utah who were teen idols like the Jackson 5. The Osmonds’ hits in the 1970s “One Bad Apple,” “Yo-Yo,” and “Down by the Lazy River” were done at FAME.

In the same year, Rick Hall was nominated for a Grammy in the “Producer of the Year” category and in 1971 Billboard Magazine named him the “World’s Producer of the Year.”

Why start another new studio when you are already successful?

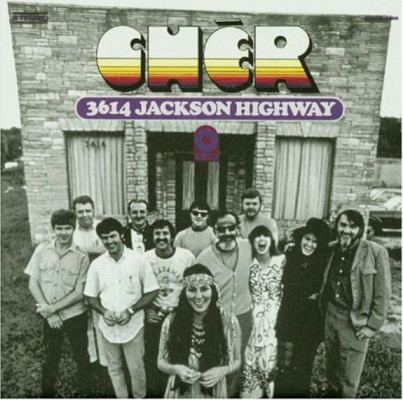

In 1969 the Swampers decided to leave FAME and started a new studio called the Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in the neighboring city of Sheffield at 3416 Jackson Highway. This address would become infamous all over the world for years to come. Barry Beckett (keys), David Hood (bass), Jimmy Johnson (rhythm guitar), and Roger Hawkins (drums) were the Swampers. The studio was unique because it was, at one time, the only studio owned and operated by musicians. The studio’s first release was by the artist Cher, who debuted her album, 3416 Jackson Highway with the cover featuring a photo of the building.

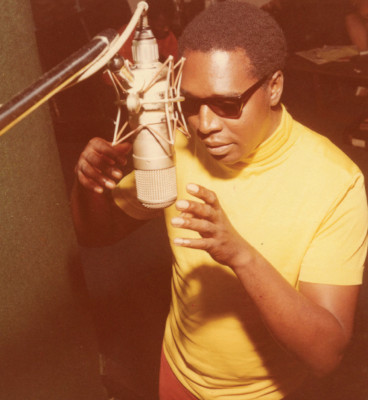

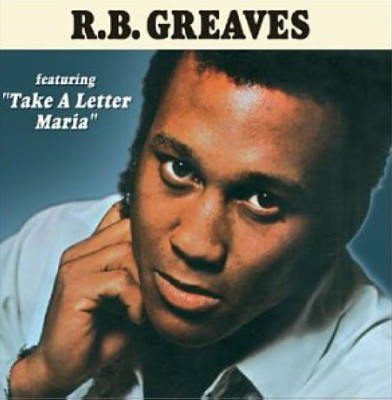

Music success was in the atmosphere in the Shoals area studios. After working with artists like Boz Scaggs, Lulu, and Arif Mardin throughout 1969, the studio found its first commercial success with “Take A Letter, Maria” by R.B. Greaves. Greaves was the nephew of the late Sam Cooke. His first hit single peaked at number 2 on the music charts and scoring Muscle Shoals Sound Studio its first gold record. The following year he scored another hit “There’s Always Something There to Remind Me.” The same week of recording with Greaves, the Swampers hosted The Rolling Stones, who cut three songs from their 1971 release Sticky Fingers: “Brown Sugar,” “You Got to Move,” and “Wild Horses”.

From 1969 to 1978, the Swampers played on over 200 albums, with over 75 Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) Gold and Platinum records, and hundreds of hit songs with artists such as Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Dylan, Duane Allman, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, Bob Seger, The Staple Singers, Rod Stewart, Leon Russell, Willie Nelson, Cat Stevens, Dr. Hook, and Eddie Hinton. By 1978, the Swampers outgrew the building at Jackson Highway and purchased a larger building closer to the banks of the Tennessee River in Sheffield.

So, what African American legends have recorded in Muscle Shoals? The list goes on and on. Although the family gospel-soul group The Staple Singers were Stax artists, they cut some of their most famous tracks at Muscle Shoals Sound Studios, including anthems of empowerment “Respect Yourself” in 1971, and the following year’s smash “I’ll Take You There,” which became a pop chart topper. Four-time Grammy nominee Candi Staton started her career in Muscle Shoals at FAME. The iconic soul artists Sam and Dave recorded their hits “Soul Man,” “Hold On, I’m Comin’” and “I Thank You” in the Shoals. James Brown, “The Godfather of Soul,” recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound. The song “It’s Too Funky in Here” was released as a single in May of 1979 and it reached No. 15 on the charts.

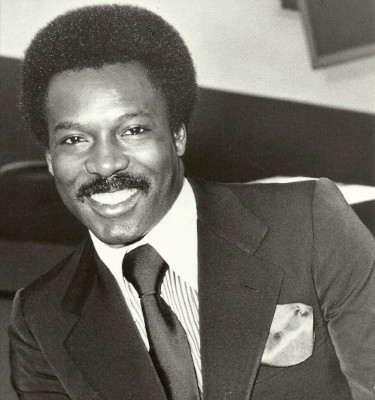

Johnny Taylor brought his talents to Muscle Shoals Sound when he recorded “One Step Beyond”, one of a string of albums with The Swampers. His big hit came in 1976 with the first single to be certified platinum (two million copies sold), the mega hit “Disco Lady”. The Blind Boys of Alabama recorded their “Almost Home” album at FAME. Keb’ Mo’ recorded “The Road of Love” for the Muscle Shoals Small Town Big Sound album. In more recent times, artists such as guitarist Eric Essix (his 2016 album, This Train) and Alicia Keys (who breathed new life into Bob Dylan’s “Pressing On”) have recorded in the Shoals.

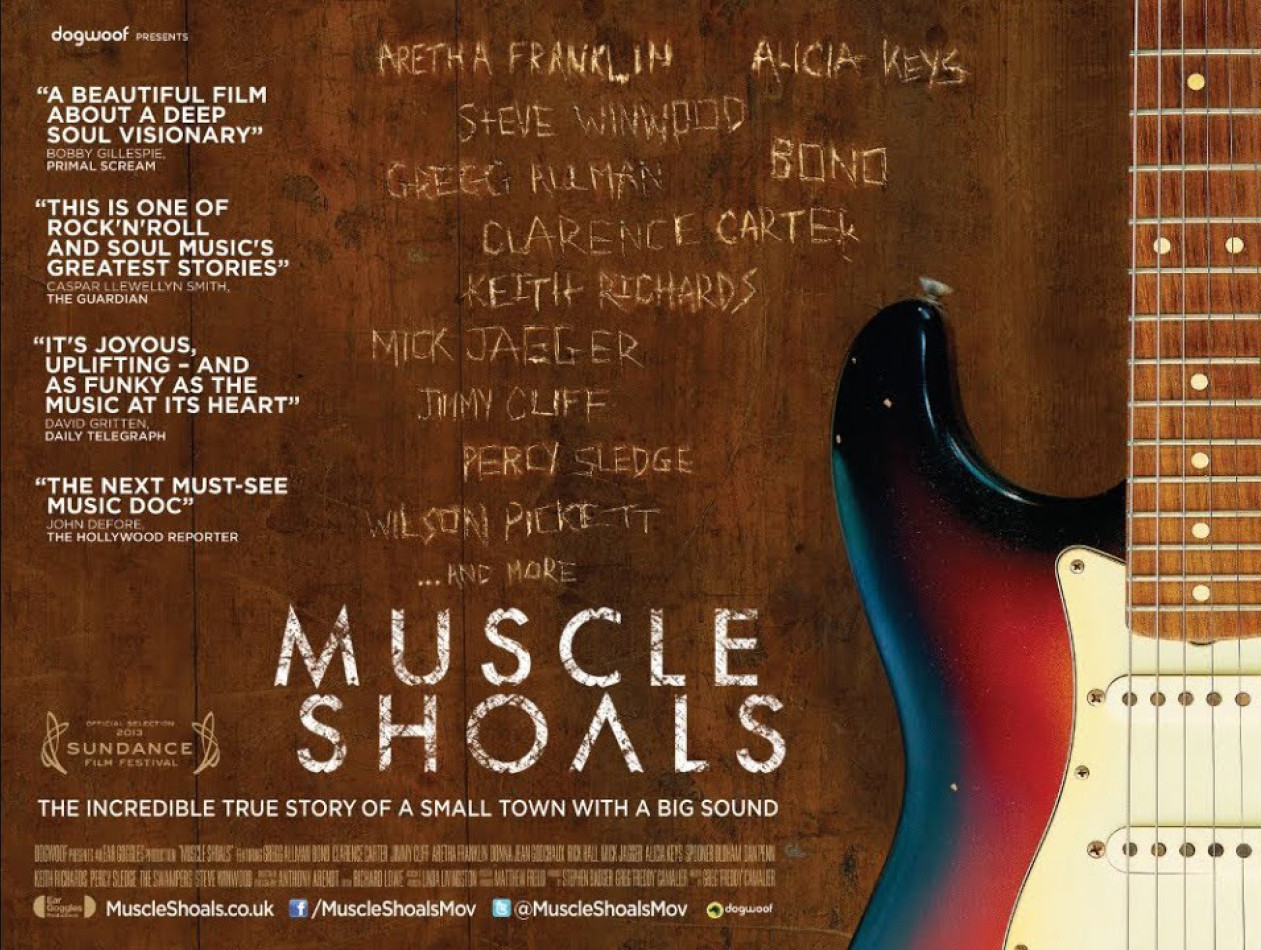

In September 2013 Greg “Freddy” Camalier directed a documentary film about FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, and the Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. The film is called Muscle Shoals. It features numerous recording artists as well as the staff and musicians associated with the studios. Camalier explored how a tiny Alabama town on the southern edge of the Tennessee River served as the source of some of the greatest American music of the 1960s and ’70s. At two competing recording studios, artists as varied as Percy Sledge and Wilson Pickett, the Rolling Stones and Traffic, Paul Simon and Jimmy Cliff, discovered and honed their sounds. And in the process, the classic tunes they produced helped fortify the mythology of the Muscle Shoals Sound.

As lovely as the artists’ takes are in the documentary, one still wonders after reviewing the film: What is it about this unlikely, rural town that produced so much great music? Is it the vibe, the history, the players, or the remoteness from pop-culture hubs like New York and Los Angeles? Those questions may never be answered.

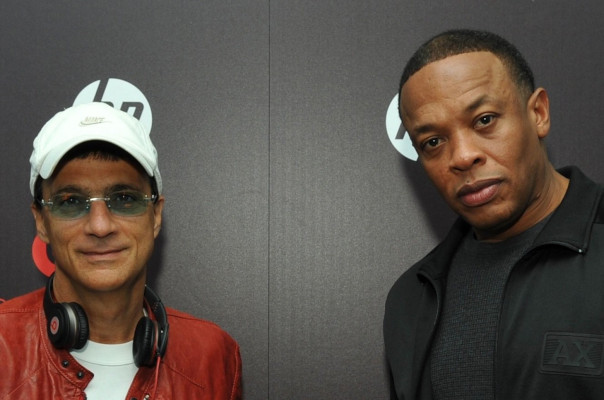

How did the well-known rapper and record producer Dr. Dre become a hero for Muscle Shoals Sound Studio? By 2013 the studio at 3416 Jackson Highway needed many upgrades and restoration. Hip hop artist Dr. Dre and music mogul Jimmy Iovine came to the studio’s aid after seeing the Muscle Shoals documentary in Santa Monica, California. Dr. Dre reached out to financially help completely restore the studio and create a record label museum.

Because of that financial gift, 82,000 people from 40 different countries have made the pilgrimage to stand in the sacred spaces where so much magic was (and continues to be) made. Since the Muscle Shoals documentary, the otherwise quiet North Alabama area, known for Muscle Shoals Sound and FAME Studios, continues to enjoy a resurgence.